Editor’s Note: This is the sixth post in Part II of the Visual Cultures of the Circumpolar North series edited by Isabelle Gapp and Mark A. Cheetham.

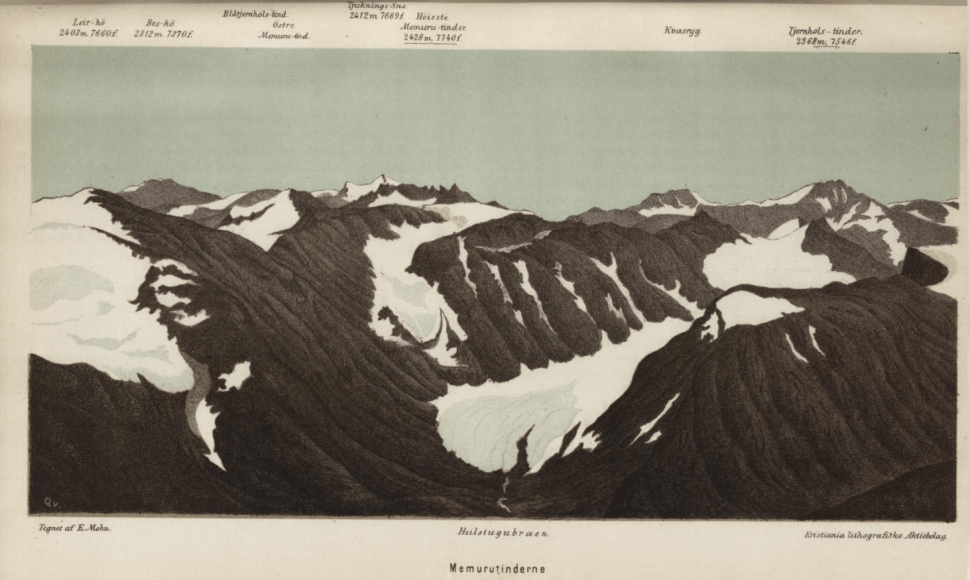

The images are sparse, reducing the mountain landscapes to the essential colours of ice and rock. There are shades of grey in places and the occasional pastel blue of a lake. These are, however, images which are beautiful in their simplicity and how they capture landscape so directly, as well as functional in their purpose. Produced from drawings made by the Norwegian teacher Emanuel Mohn (1842-1891), these lithographs show Norwegian mountain landscapes in stark, if elegant, terms, depopulated and monochrome. However, they also offer an insight into the cultures of travel, tourism and nation building in Norway in the late nineteenth century. The increased popularity of mountaineering in Norway in the period produced its own textual and visual culture and Mohn’s lithographs, especially the locations in which they were reproduced, contributed to how mountain regions were accessed.

The images, produced in the late 1880s, show panoramic views of notable Norwegian mountain ranges. They offer vistas in fine weather, providing unbroken lines of sight, and the main peaks are labelled with annotations, including their heights in feet. As such, these are more than aesthetic visions; they are also practical guides. Mohn was an early member of Den Norske Turistforening [The Norwegian Trekking Association] (DNT), an organisation which worked to make Norwegian landscapes accessible for travellers and tourists from its founding in 1868. DNT worked in mountainous areas like Jotunheimen in central Norway to construct roads, paths and cabins, as well as publishing guides and maps. Mohn wrote for DNT’s yearbook from 1872 and several of his panoramas were published there. The panoramas often accompanied descriptions of routes that mountaineers could take, as well as written overviews of the landscapes. Mohn published several collections of his panoramas, as well as a guidebook to Jotunheimen in 1879.1 Jotunheimen was a particular area of interest for mountaineers, with numerous cabins being constructed in the 1880s to accommodate increasing numbers of travellers. Jotunheimen was also a popular destination for Norwegian and Danish artists, like J.F. Willumsen, whose Jotunheim (1892-1893) drew on a similar visual language to Mohn’s lithographs.

Mohn’s images, beyond their practical use for orienting mountaineers, also owe a lot to the tradition of the panorama. Similar depictions of mountain ranges were common in the nineteenth century, bringing together the spectacular and a gaze which ordered the landscape.2 Mohn’s panoramas also suggest another part of DNT’s project: making the Norwegian nation, and its landscapes, known. Mohn was contributing to a national project, one which saw authentic Norwegian identity as found in the natural and in supposed wildernesses. Making this landscape accessible for Norwegians was crucial for building national identity.3 Mohn’s lithographs sit alongside the photography of Knud Knudsen, Axel Lindahl and Anders Beer Wilse as visual representations of Norwegian landscapes that helped to define the nation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Photography, however, also defined who belonged to the nation. As Patricia Berman has shown, anthropological photography was used to define and monitor who was “Norwegian”.4 It provided a supposedly objective measure by which to exclude certain groups from the nation, particularly Sámi and Kvens, as well as influencing ideas about the racial superiority of certain groups beyond the Norwegian context. This work of photography as making the nation by both recording its landscapes and excluding certain groups through scientific claims is worth considering when we look at Mohn’s lithographs. They are conspicuously empty of people, showing both a knowledge of the landscape to claim it and also the sort of empty landscapes free for certain claims. As with National Romantic landscape painting, the Norwegian landscape is made appealing through the absence of life.

Mohn’s lithographs also suggest a history beyond the nation. Norwegians were not the only people making Jotunheimen and other Norwegian landscapes into tourist spaces. The British mountaineer William Cecil Slingsby, known as the “father of Norwegian mountaineering”, climbed extensively with Mohn, including the first ascent of Store Skagastølstind, a prominent mountain in Jotunheimen.5 Slingsby referred to Mohn as his “fjell kammerat” – “mountain comrade” – and also wrote extensively for the DNT yearbook.6 Slingsby also describes using an edition of the yearbook as a guide when travelling – an indication that Mohn’s lithographs could have been used for a similar purpose.

Slingsby also praised the work of DNT in making Norwegian mountain regions more accessible, as did other British travellers. For A.F. Mockler-Ferryman, DNT had made life “smoother for the adventurer”.7 Mockler-Ferryman also supported removing Sámi from their lands where possible, to support both Norwegian farming and tourist travel. Other British mountaineers used DNT infrastructure and also photographed Norwegian landscapes and people. Particularly notable was Elizabeth Le Blond, who climbed in Sápmi in the 1890s and was a keen photographer. Howard Priestman climbed and photographed widely across central and southern Norway, similarly contributing to visual representations of the country.

Mohn’s images, for their deceptive simplicity, reveal more about nineteenth-century projects of categorising and knowing place than they would initially seem to. The panoramic perspective both claims the landscape and guides the traveller through it. Mohn’s lithographs can be read as containing multiple aspects of the nineteenth-century Norwegian national project. Moreover, as Simone Abram and Gro Ween have suggested, DNT is still part of the project of building the Norwegian nation.8 However, DNT, and Mohn himself, did not simply produce images and discourses in national terms. Together with fellow mountaineers like Slingsby, Mohn’s images are part of a broader transnational co-construction of place. Travellers from outside Norway, however, tended to reinforce certain ways of seeing Norway, especially in terms of who was excluded from the nation. Mohn’s lithographs therefore appear simple but open up alternative ways of thinking and different histories of this part of the circumpolar north.

Notes

[1] Rune Slagstad, Da Fjellet Ble Dannet (Oslo: Dreyer Forlag, 2018), 141.

[2] Victorian della Dora, Mountain: Nature and Culture (London: Reaktion, 2016), 126-8. Slagstad also discusses the influence of panoramas on Mohn. Da Fjellet Ble Dannet, 157-8.

[3] Finn Arne Jørgensen, “Knowing, Sharing, and Experiencing Wilderness”, Ant Spider Bee: Exploring the Digital Environmental Humanities (September 2015), https://www.antspiderbee.net/2015/09/09/knowing-sharing-and-experiencing-wilderness/ (last accessed 20th January 2023).

[4] Patricia G. Berman, “From Folk to a Folk Race: Carl Arbo and National Romantic Anthropology in Norway” in Marsha Morton and Barbara Larson (eds.), Constructing Race on the Borders of Europe: Ethnography, Anthropology, and Visual Culture, 1850-1930 (London, Bloomsbury, 2021): 25-49.

[5] Paul Readman, “William Cecil Slingsby, Norway, and British Mountaineering, 1872-1914”, English Historical Review, vol. CXXIX, no. 540 (October 2014), 1102.

[6] William Cecil Slingsby, Norway. The Northern Playground. Sketches of Climbing and Mountain Exploration in Norway between 1872 and 1903 (Edinburgh: David Douglas, 1904), 124.

[7] A.F. Mockler-Ferryman, In the Northman’s Land: Travel, Sport, and Folk-lore in the Hardanger Fjord and Fjeld (London: Sampson Low, Marston and Co., 1896), 217.

[8] Gro Ween & Simone Abram, “The Norwegian Trekking Association: Trekking as Constituting the Nation”, Landscape Research, vol. 37, no. 2 (April 2012): 155-171.

Feature image: Emanuel Mohn, “View from Galdhöpig to the South-West”, Publisher: F. Beyer (Bergen, 1887), Collection: Nasjonalbiblioteket (https://www.flickr.com/photos/national_library_of_norway/23775970812/)

Latest posts by Christian Drury (see all)

- Review of the Ski Like a Girl Podcast - July 10, 2025

- Norwegian Mountain Lithographs: Mapping the Nation and Guiding the Tourist - February 9, 2023