Editor’s Note: This is the second of two posts in which freelance researcher David Brownstein responds to the ongoing Fairy Creek protests by reflecting on the long history of logging protests in B.C.

This is the second part of two posts on the history of BC logging protests. Part 1 began with the observation that contemporary logging protests are but the most recent statement in a longstanding conversation. Four cases were then presented as examples. Here, in part 2, another two cases further identify several enduring themes — the desire to protect old growth; the role of the press; and difficulties created by how BC grants logging rights — that connect past logging controversies to those of the present.

5) Cathedral Grove, Vancouver Island, 1929-1947

For the iconic Cathedral Grove, early sale of land outright (rather than lease of logging rights) would create conflict between tourism and the forest products economy. Colonization placed the traditional territories of the K’ómoks and Tseshaht First Nations, and the contemporary Te’mexw Treaty Association, inside the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway land grant. Adjacent to Cameron Lake, the land that supported this famed collection of large trees was sold to the Victoria Lumber & Manufacturing Company in 1889. Eleven years later, James Fletcher, Dominion entomologist and botanist, visited the trees that would come to be known as “Cathedral Grove”, as part of a Port Alberni stop on his Farmer’s Institutes speaking-tour. Fletcher’s hosts were James Robert Anderson, Deputy Minister of Agriculture (and Natural History Society of BC member), and the amateur entomologist Reverend George Taylor. Fletcher met with the Farmer’s Institutes regarding federal support in clearing the large stumps that impeded Alberni Valley farming. However, at this same meeting, he urged the farmers to do everything in their power to preserve the magnificent forest around Cameron Lake.1

In 1909 one of our logging-protest frequent flyers, the Natural History Society of BC, sent a resolution to the Vancouver Island Development League seeking lobbying help to reacquire the alienated land, and to form a “forest reserve and game sanctuary” at Cameron Lake.2 Anderson revived this call in 1919, with a letter to the Port Alberni City Council. In parallel to the previously described request at Green Timbers (see Part 1), Anderson sought to turn the Cameron Lake timber into a War Memorial. Despite frequent suggestions that the trees were under imminent threat of logging, they continued to stand.

Over the next years the fate of Cathedral Grove was omnipresent in the press, with one noticeable surge of concern in 1936, coinciding with rumours of impending logging, and a Cowichan Leader editorial that revealed that the Victoria Lumber and Manufacturing Co was willing to sell their holdings, or exchange them for others elsewhere.3

Over the years many people and organizations were involved in protests and campaigns, but one group is especially worthy of our attention. The July 1942 formation of The British Columbia Natural Resources Conservation League, its members claimed, grew out of the immediate necessity of saving the Cathedral Grove timber, and the timber at the entrance to Strathcona Park on Buttle Lake.4 Unlike previous organizations that took on anti-logging activities, the League’s sole purpose was to banish logging from areas of concern, making it a direct precursor to today’s modern environmental organizations. Like contemporary activists, as depicted in the figure above, the League sought to influence forest policy decisions via public opinion, as shaped by the media.

Unlike previous organizations that took on anti-logging activities, the British Columbia Natural Resources Conservation League’s sole purpose was to banish logging from areas of concern, making it a direct precursor to today’s modern environmental organizations.

The Natural Resources Conservation League was organized at a meeting held in the Hotel Vancouver.5 While initially a Vancouver committee, in time the original board became an umbrella provincial organization, establishing branches in Victoria, Nanaimo, Courtenay, Port Alberni, and Cameron Lake.6 The League’s leadership included Frank Burd as honorary President (publisher of the Vancouver Daily Province), and H.H. Stevens (former federal Conservative cabinet minister, now infamous for his anti-Asian views) was elected President. Other key figures were municipal politicians, and those active in existing Tourist organizations or Automobile clubs.

“If the League had been in existence some years ago, the Green Timbers would never have been cut” they proclaimed.7 Perhaps. Lending credence to their boast, the organization sponsored a series of radio addresses, and they travelled, making presentations directly to Premier John Hart and the provincial cabinet. In this way, the League’s methods were quite unlike those of today’s Flying Rainforest Squad. And, unlike other historical protests described above, which tended to be projects limited to the privileged, there was more widespread, vocal, grassroots support that the Cameron Lake trees ought not to be logged.

After lengthy negotiations with the provincial government, on November 28th, 1944, newspapers reported that the then-rights-holder H.R. MacMillan, businessman and former chief forester, had made a gift of the grove and surrounding hundreds of hectares.8 It was declared a provincial park in 1947.9

The BC Natural Resources Conservation League was active until the mid-1950s. H.H. Stevens claimed credit, via the League’s interventions, for having preserved scenic timber stands at both Cathedral Grove and Buttle Lake. Timber on Hollyburn Ridge, at Nanaimo Lake and in other areas of BC, were also conserved, in part, through the efforts of the League.10

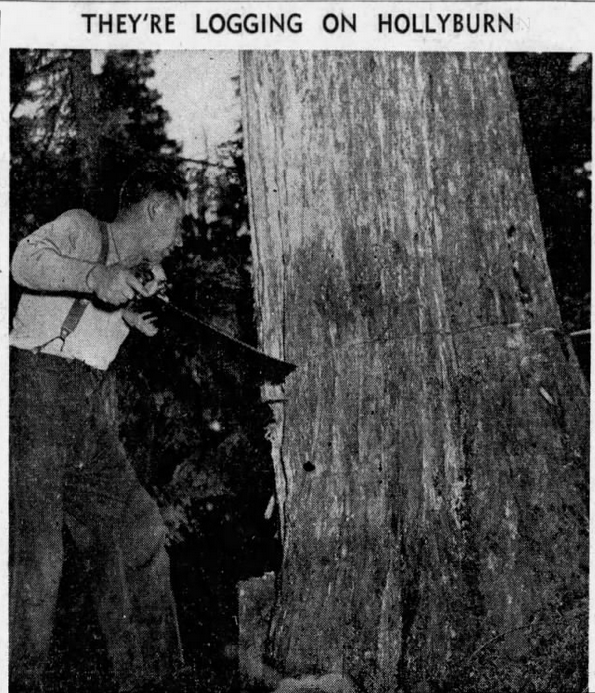

6) Hollyburn Ridge, West Vancouver, 1938-1944

In this last case, West Vancouver’s Hollyburn Ridge, we encounter a dual conflict between logging and both health and recreation. Like the previous episodes, the provincial government had sold logging rights in advance of the Lower Mainland’s urbanization, insensitive to the future incompatibilities that would emerge and fuel the dispute. This would be another dramatic example of lurch logging, a strategy used by the rights-holder to whip up public anxiety, keep the story in the press, and pressure the government for a financial resolution.

When Frank Henry Heep, of Los Angeles, insisted in 1938 that he “ha[d] to log” Hollyburn Ridge on Burrard Inlet’s north shore, home of the Squamish, Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh peoples, “business men and sports enthusiasts” were equally insistent that Heep’s logging operations be disallowed. The logging leases lay just to the west of the Capilano and Seymour watersheds that had seen such controversy between 1923 and 1933.

When Frank Henry Heep, of Los Angeles, insisted in 1938 that he “ha[d] to log” Hollyburn Ridge on Burrard Inlet’s north shore, “business men and sports enthusiasts” were equally insistent that Heep’s logging operations be disallowed.

Vancouver Mayor George C. Miller, among others, noted that the then current depressed price of logs rendered the operation unprofitable. It is possible that Heep perceived a business opportunity in extracting money from his investment through means other than logging, noting that “I realize that the area is much more valuable as a park than as a logging operation.” Heep suggested that the city purchase his leases for $125,000, an offer the city declined. “I paid $137,000 for the leases, and I have been paying about $1000 a year taxes on it for twelve years,” Heep complained.11

The voices protesting Heep’s plans were diverse, representing the deepest opposition to any logging yet, perhaps except for that of Cathedral Grove. Mrs Dorothy Steeves, North Vancouver MLA, wired a strong protest to Hon A. Wells Gray, Minister of Lands, urging a timber exchange. Dr. G. H. Worthington, President of the Vancouver Tourist Association, also believed that action should be taken to remove the possibility of logging operations for all time, noting that “I think they are just threatening to log the timber… everyone knows that the market for logs is not good.” The Hollyburn Ridge ski clubs, the Vancouver Board of Trade and Junior Board of Trade, the West Vancouver Council, the North Vancouver Board of Trade, the Vancouver Park Board and the Vancouver Tourist Bureau were all among the organizations fighting the logging. The ski promotion committee of Hollyburn Ridge, representing some thousand skiers and 200 cabin owners “endorsed steps already taken.” The Vancouver Local Council of Women directed a strong protest to the Premier and Minster of Lands, as well as the Federal Government. Many advocated payment for the logging rights or to exchange timber limits with the lease holders.12

As in other cases, Premier Pattullo at first declined to use provincial money, citing the cost of such a precedent. Purchasing scenic timber around the province would be an enormous expense and Pattullo concluded that extinguishing the logging rights was a matter for the municipality of West Vancouver. West Vancouver indicated that it would pay half of the costs, assuming that the province paid the other half. West Van also noted that, given that the treed mountains provided a beautiful backdrop for all of greater Vancouver, the larger city to the south should also contribute, as it was their view.13

The Vancouver Parks Board envisioned the whole North Shore area as a great metropolitan winter playground with protected watershed areas, declaring that the Provincial Government should expropriate Hollyburn Ridge for park purposes.

Heep cashed out, selling his rights to the reorganized Cypress Creek Logging Co. Ltd, which initiated some short-lived logging operations in July 1940.14 Three years would go by before the next flurry of activity. H. H. Stevens, of The BC Natural Resources Conservation League, made representations to the Provincial Government to exchange the Hollyburn timber for logging rights on Vancouver Island.15 Plans for this trade (and to incorporate the Hollyburn property into a vast North Shore park area) fell through, and logging began anew.16 Given the proximity to the drinking water supply, the municipal council insisted that the operators supply a doctor’s certificate on each man and that a complete list of employees, with changes, be kept up to date.17

In this next 1943 iteration of the controversy, yet more groups joined. The BC Mountaineering Club sought support for their protests in the local section of Alpine Club of Canada, the Vancouver Natural History Society, the Burrard Field Naturalists’ Club, the University Outdoors Club, and local ski clubs.18 In the eyes of the BC Forest Branch, however, on-site logging equipment worth $37,000 and the crew of 20 loggers was again called “a bluff” to force the government to make an expensive deal with the owners. The Hollyburn Logging Company refused to say on what scale the operations would be carried out.19

The Vancouver Parks Board envisioned the whole North Shore area as a great metropolitan winter playground, with protected watershed areas, declaring that the Provincial Government should expropriate Hollyburn Ridge for park purposes.20 The Board sent invitations to attend a Stanley-Park-hosted protest-meeting to five provincial cabinet ministers, Mayor Cornett and the City Council, Board of Trade, Junior Board of Trade, Tourist Association, the reeves of West Vancouver, Burnaby and Richmond, Mayor Mott of New Westminster, Commissioner Morden of North Vancouver, representatives of the BC Conservation League and the ski zone committee.21 The Parks Board’s efforts kept the issue alive in the press. Such deep opposition to the logging forced the province to intervene, as it had in the other situations explored above.

The next spring, Premier Hart visited the Hollyburn site on April 26, 1944. One year after a similar announcement regarding Strathcona Park, Hollyburn too, would stay green. In this case, the Provincial Government exchanged Hollyburn Ridge timber holdings for five timber licenses at Elk Bay, north of Campbell River, on Vancouver Island. Holders of the Elk Bay timber believed that the limits might contain considerably more than 45,000,000 feet of mixed fir, cedar and hemlock. And, to the satisfaction of both protestors and compensated loggers, Hollyburn would be incorporated into the government’s plan for a North Shore “evergreen parkland.”22

Some Concluding Thoughts

Lorna Beecroft’s viral photo, with which this series began in Part 1, is but a recent statement in a longstanding conversation. Through a study of the six cases, we can identify several enduring themes that connect past logging controversies to those of the present. Historical actors, as now, feared that future generations would never see old-growth trees. The fate of old growth is an emotionally fraught topic, which polarizes communities, and sometimes devolves into violence (Deadman’s Island). The press was used by both British Columbians and outsiders, who were passionate about forest policy (as in the Green Timbers and Strathcona Park “protests”). And, perhaps most importantly, extinguishing existing logging rights has always been terribly expensive, a cost ultimately born by provincial taxpayers. The Seymour and Capilano watersheds saw the first rights buyouts, while Strathcona Park introduced the timber exchange.

The personalities in each controversy reflected the locus of power at the time. While the characters involved changed by decade, location, and motivation, in almost all cases, the protesters lived in Victoria or Vancouver. On the whole, most people didn’t care about trees coming down somewhere, they simply didn’t want their trees to be felled. And initial complaints came from pre-existing organizations with allied goals (which is to say, almost no groups were created with the purpose of protesting logging). In time, this would shift, to see organizations created around particular protest movements with greater geographic scope, as exemplified by the British Columbia Natural Resources Conservation League.

There are also many differences when historical protests are compared with those of today. The federal crown ceased to have a role in these conflicts after 1930, when the railway belt lands were returned to provincial control. This change was important because of our six cases, the only trees logged — Deadman’s Island and Green Timbers — were both on federally managed land. The particular motivations to prevent logging have also shifted remarkably, with biodiversity, climate change and reconciliation now rightly having eclipsed recreation. More importantly, Indigenous voices were entirely absent in the six historical cases, and this represents an enormous discontinuity. Indeed, I have chosen my dates and cases with this in mind. Subsequent logging disputes on the West coast of Vancouver Island and Haida Gwaii were intermingled with reassertions of First Nations title. This is a topic that demands its own examination (and one that I have been assembling, but it is not yet ready to share).

This brings us to the greatest difference of all. Neither contemporary protestors nor the demands of reconciliation will be satisfied by exchanging old growth logging rights in one place for those in another. Corporate gifts to the citizens of British Columbia, as in the Strathcona Park leases or Cathedral Grove lands, are unlikely to function as an escape hatch, as they did in the past. Because today’s protesters have adopted a more universal mandate than their historical predecessors, those today will not be content to have just “their” trees remain standing. The Rainforest Flying Squad’s goal is to end all old growth logging. This means that, without a new contemporary invention (involving fancy carbon financing?), there is only one historically tested way out of the current Fairy Creek old-growth controversy: the public buyout, a taxpayer-funded scheme by which existing licensees are compensated for having their logging rights extinguished, in favour of either transfer to First Nations, or preservation. Anticipate that this process will be fraught with disagreement. Protestors and government appear eager to proceed faster than either First Nations or industry. Those different expectations need calibration. And it is safe to assume that mitigating historical contingencies will be expensive. No doubt this is why the newly introduced Bill 28 gives the minister complete control over compensation for seized tenure rights.

Despite divergent views, I am optimistic that the present old-growth controversy can be resolved and replaced by a new constellation of relationships. Though possibly nobody will be thrilled with the immediate result, let us hope that the new arrangement is one with which we can live.

My thanks to Jennifer Howes, James Murton, Eric Andersen, John Parminter and Ira Sutherland for sharing their constructive thoughts. Chelsea Shriver and Claire Williams of UBC Rare Books and Special Collections were also most helpful with access to material and a photo permission.

Feature Image Credit: The Province, 6 Aug 1942, p 9

- Jan Peterson. 1996. Cathedral Grove: MacMillan Park (Oolichan Books, Lantzville), 23-24; David J. Sandquist. 2000. “The Giant Killers: Forestry, Conservation and Recreation in the Green Timbers Forest, Surrey, British Columbia to 1930,” unpublished MA thesis, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, p 69.

2. Paula Young. 2011. “Creating a ‘Natural Asset’: British Columbia’s First Park, Strathcona, 1905-1916″ BC Studies, no 170, p 21.

3. Peterson, p 49, 63.

4.Roderick L. Haig-Brown. “The Lost Quarter Century: A Noted Writer Tells of the Recent Movement Toward Forest Conservation In British Columbia,” The Vancouver Province Magazine, 17 Oct 1942, p 2 (specifically, on the Conservation League, column 5).

5. “League Formed to Conserve B.C. Resources,” The Vancouver Sun, 4 Jul 1942, p 15; “Conservation League Will Guard Timber,” Nanaimo Daily News, 8 Jul 1942, p 1.

6. “League to Save Scenic Timber Formed in BC,” Times Colonist, 14 Aug 1942, p 16.

7.”Scenic Attractions of Province Endangered: Conservation Group Opens Fight to Save Beauty Spots of B.C. from Logger’s Axe,” The Province, 15 July 1942, p 20.

8. “Cathedral Grove Timber Area Presented to BC,” Nanaimo Daily News, 28 Nov 1944, p 1.

9. Peterson, p 89.

10. “Yukon Area Set Aside for National Park,” The Vancouver Sun, 8 Jul 1943, p 13.

11. “’I’m Not Bluffing,’ Says Hollyburn Logger, As Protests Flood Victoria: Mayor and Tourist Executive Demand Action to Save Trees,” The Daily Province, Vancouver, 13 Jun 1938, p 1.

12. Ibid; “May Represent Council Abroad,” The Province 18 Jun 1938, p 13; “City Organizations Rush to Defense of Hollyburn Ridge: 1,000 Skiers Voice Mass Protest of Logging Plan,” The Vancouver Sun 13 Jun 1938, p 3.

13. “BC Not To Buy Ridge Timber,” The Province, 14 June 1938, p 22.

14. “Logging Starts on Hollyburn,” The Vancouver Sun, 19 Jun 1940, p 11.

15. “Move to Save Hollyburn Timber,” The Vancouver Sun, 7 Jul 1943, p 14.

16. “Park Project Ends: Plan To Log On Hollyburn,” The Province, 13 Oct 1943, p 2.

17. “Logging to Start On Hollyburn Ridge,” The Vancouver Sun, 13 Oct 1943, p 6.

18. “Mountaineering Club Protests Ridge Logging,” The Province, 21 Oct 1943, p 6.

19. “Logging Starts: Timber Falls On Hollyburn,” The Province, 23 Oct 1943, p 20.

20. “Park Board to Make Last Attempt to Halt Logging on Hollyburn Ridge: Holland Would Have Province Expropriate Lands for Park,” The Province 13 Nov 1943, p 22.

21. “Hollyburn Ridge: Plan Logging Protest Meet,” The Province 24 Nov 1943, p 15; “Expropriation Urged: Park Board Plans to Protest Logging Plans for Hollyburn,” The Province, 27 Nov 1943, p5.

22. “Holyburn Owners Get Trade of Vancouver Island Timber,” The Province, 16 Sept 1944, p 29.

Latest posts by David Brownstein (see all)

- What is the History of Logging Protests in British Columbia? Part Two - January 14, 2022

- What is the History of Logging Protests in British Columbia? - December 22, 2021

- Archival Donation: Western Forest Products - July 26, 2016

- In Celebration of International Day of Forests: A Forest History Archival Donation Guide - March 21, 2015

- The Cloud Will Not Remember Everything Forever: Some Thoughts Prompted by Another Forest History Archival Donation - October 6, 2014

- History mysteries at the Association of BC Forest Professionals Meeting - August 11, 2014

- June is Forest History Month: Special issue of the Forestry Chronicle. - June 6, 2014

- Archival donation: the Dr Hubert William Ferdinand Bunce fonds. - May 26, 2014

- Adventures along the archival commodity chain: the Truck Loggers Convention. - May 2, 2014

- A rare event: forest history on the sports pages. - March 30, 2014