The following blog post has been adapted from the paper “Climate Change and the Hockey Cultural Heritage Landscape” presented on April 22, 2017 at the Carleton University School of Indigenous and Canadian Studies 12th Annual Heritage Conservation Symposium, Dynamic and Migrating Landscapes: Re-visioning Heritage Conservation.

Hockey fulfills a lot of roles in Canada: It’s a sport, a past-time, a form of entertainment, and, frequently, a symbol for nationhood and identity. As a cultural heritage specialist, I interpret hockey through a very different lens. I see hockey as a cultural heritage landscape, one that retains an important social role in contemporary society and one that is threatened by climate change.

UNESCO describes Cultural Heritage Landscapes (CHLs) as cultural properties that represent the “combined works of nature and man.” They “express a long and intimate relationship between peoples and their natural environment.” CHLs are “illustrative of the evolution of human society and settlement over time, under the influence of the physical constraints and/or opportunities presented by their natural environment and of successive social, economic, and cultural forces, both external and internal.”

The origins of hockey are very closely tied to the natural heritage resources of Canada. Born of the Canadian winter, early forms of hockey likely evolved from a combination of Indigenous and European precursors, and first played on our many lakes, rivers, ponds, and wetlands. European settlers altered this landscape by building dams, locks, canals, and mill ponds. Hockey quickly found a home on these more reliable and controlled water sources.

Soon people began to alter the landscape specifically to play hockey. For example, in the early 1900s the school kids of Hornby, Ontario would flood a tributary of Sixteen Mile Creek in the lowlands across the road from their school every autumn to build their hockey rink. They built a warming hut and clubhouse and maintained a rink at the site for over forty years. By necessity, early rinks were built in low areas near to a reliable water source.

As the sport spread communities began to build special purpose outdoor rinks, a tradition that is still practiced today, taught and repeated every year as an important winter ritual. Town rinks became community-driven, planned resources, often found in parks. Community parks are also commonly found in low lying areas, near water sources, usually within the floodplain or considered a part of the stormwater management system. In urban areas rinks are built on under-utilized paved surfaces like parking lots or driveways or in private backyards.

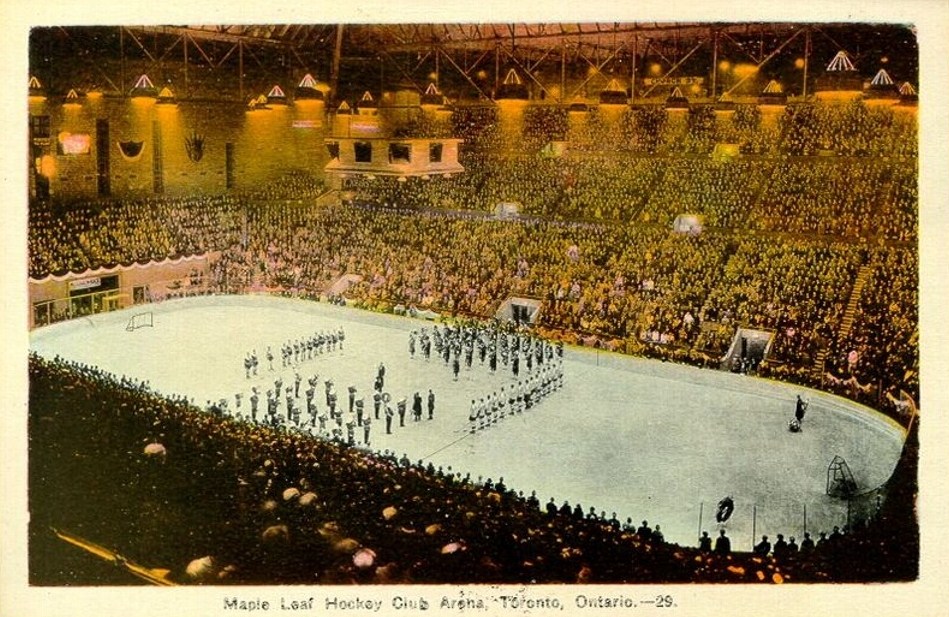

The emergence of the indoor rink introduced built heritage resources to this landscape. Arenas were safer, warmer and protected spaces. These arenas also offered a place for spectators to sit, changing the game from a participatory activity to a form of entertainment.

More importantly, these resources provided the foundation upon which the culture of hockey was built. Hockey rinks and arenas, such as the Belgrave Arena, a natural ice arena in Belgrave, Ontario, are important third spaces in communities across Canada and are often the centre of social life in both small towns and large cities.

The development of the hockey arena culminated in the emergence of the professional hockey arena. In 1931, Maple Leaf Gardens was the first arena to be built for broadcast, sending out play-by-play coverage on the Canadian National Railway radio network simultaneously to 27 stations across Canada, a tradition that would become the CBC’s Hockey Night In Canada. This infrastructure cemented hockey as a core form of entertainment in Canada, but more importantly, it created a shared experience coast-to-coast, something that is hard to accomplish in a country as large and diverse as Canada.

Together these resources form a massive cultural heritage landscape that has evolved over time, driven by environmental, social, economic, and cultural imperatives, in association with, and in response to the natural environment of Canada. Hockey reflects the early history and growth of Canada as much as it retains an active social role in contemporary society. However, hockey resources, like rinks and arenas, are under-recognized in the cultural heritage field and often have no formal heritage status.

For example, the Canadian Register of Historic Places lists 2485 churches, 1566 schools, 1396 farms, 1111 train stations and a mere 37 rinks or arenas. Despite the pervasive role of hockey in Canada, there are many threats to this cultural landscape: The cost of playing the sport, which limits the participation of New Canadians and low-income families; the deterioration of arenas in communities that are suffering economically; and our increased understanding of the risks of contact sport. None of these threats, however, seem as insurmountable as the threat of climate disruption and the changing, often unpredictable nature of Canadian winters.

In the 2012 paper “Observed decreases in the Canadian outdoor skating season due to recent winter warming,” researchers from the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at McGill University consider historical weather patterns across Canada between 1951 and 2005 and establish the specific weather conditions needed to build and maintain an outdoor rink. They define the start of the outdoor skating season as the last day of three consecutive late autumn days with a maximum temperature below -5 °C, and measure the length of the season as the number of days with a maximum temperature below -5 °C. The paper demonstrates clear warming trends in Canada since the 1950s, with later starting outdoor skating seasons in British Columbia, southwest Alberta, southern Ontario and Québec and shorter seasons in all regions of Canada, with the exception of the Maritimes.

“Winters too warm to skate? Citizen-science reported variability in the availability of outdoor skating in Canada” uses climate change prediction models to predict the future number of total viable skating days. Written in 2015, this paper uses data collected from RinkWatch, a citizen science project, to compare skating conditions to temperature data for 10 cities across Canada, and establishes region-specific criteria for skatable days. It then applies these criteria to the daily temperature simulations of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change A2 emissions scenario to predict future ice conditions. The paper predicts that the number of skating days by the year 2090 will decline on average by 34 percent in Toronto and Montreal, and 19 percent in Calgary.

Poor conditions for rinkmaking and fewer skatable days may already be resulting in the loss of the outdoor rink and the unorganized play that these community-defining spaces provide. Rinks are built annually by dedicated parents and community members. This is an important ritual in many parts of the country, especially in small communities. The shared traditional knowledge of rinkmaking is passed on from generation to generation through the act of building the rinks themselves. Anecdotally, this knowledge or role has already been lost in many communities due to short seasons or a series of abnormally bad years. Natural ice arenas, built before artificially-cooled rink surfaces were the standard, are also a disappearing resource, as are the communities that formed around them.

One example of a hockey CHL at risk is Cedarena, an old-fashioned outdoor rink located in the village of Cedar Grove in Markham, Ontario, within the boundary of the new Rouge National Urban Park. Cedarena, in continuous use since it was first opened in 1927, is entirely community built and is run by local volunteers. Located in a low-lying area near the Little Rouge Creek and along the suspected route of the Carrying Place Trail, Cedarena has a great ice surface and an old wood stove heated warming hut, just like the one built by the children of Hornby, Ontario.

It also didn’t open in the winter of 2016 for the first time in 88 years and has remained closed for the past two years. While the rink didn’t open for a number of reasons, for example, a lot of the volunteers are from an increasingly small rural population in an increasingly urban Markham, the repeatedly stated and widely accepted explanation is that the skating season is too short and too warm for the rink to be economically viable.

This trend has larger implications for hockey as a sport. This 2007 article in Globe and Mail, dramatically titled “When backyard dreams melt.”, essentially argues that Wayne Gretzky couldn’t happen in our current climate. The unstructured, unorganized play that Gretzky was afforded in his own backyard rink is often credited for his success and for changing the game forever. But winters are now too short where Gretzky grew up in Brantford, Ontario, to justify a backyard rink. In the article, legendary hockey dad Walter Gretzky states “You can’t make a rink like this anymore because the winters aren’t cold enough, If you’re lucky, you might have two weeks, maybe three weeks. But you can’t get three or four weeks in a row of cold. You get one day cold, next day warm. You can’t get a rink going.”

Whether this threat is fully acknowledged or not, hockey and recreational skating communities have already started to respond to climate change in a number of interesting ways. Increasingly, municipalities are choosing to invest in artificial outdoor rinks and skating trails, an expensive undertaking and an option not available to small towns with ageing existing rinks and ice infrastructure.

The Belgrave Arena has focused its limited resources on reinforcing its role as an important third space in the community. The arena is a cornerstone event space and is very actively used by local groups for fundraisers and social gatherings. The Fowl Supper, which is held at the arena the week before Thanksgiving, feeds over 1,000 locals and visitors every year, serving an extended community of people in under 10 minutes. This fundraiser allows the rink to stay self-sufficient. The Belgrave Arena can’t be used for organized hockey anymore due to a lack of dependable ice, but a dedicated group of trustees ensures that public stake is held at least a few times each winter, weather permitting.

New arenas are beginning to recognize the relationship between hockey and the environment. The Harry Howell Arena, constructed in October 2014 just outside of Hamilton, Ontario, is one such facility. It is a LEED Silver certified building and is 40% more energy efficient than arenas of similar size. Features such as geothermal heating and cooling, daylighting, natural ventilation, electric car charging stations and the utilization of recovered waste heat allows this building to respect and even improve the environmental health of the community it serves.

Finally, RinkWatch is a citizen science research initiative that helps environmental scientists monitor winter weather conditions and study the impacts of climate change on the hockey cultural heritage landscape. Organized by researchers at Wilfrid Laurier University, the site has gathered information about skating conditions on more than 1,400 outdoor rinks and ponds across North America since 2013. RinkWatch has also become an online gathering space for people who love rinkmaking, where they can share their experiences and build a broader community. This type of initiative raises awareness, while also encouraging people to retain the traditional skill of rinkmaking, and encouraging new people to learn and build rinks in their communities.

These responses to climate change show the resilience of communities and the desire to continue the tradition of rinkmaking, skating and pond hockey into the uncertain environmental conditions of the near future.

Lauren Walker

Latest posts by Lauren Walker (see all)

- The Commodification of Hockey in Rupert’s Land - November 11, 2020

- The “Pig Ladies” of Huron County - June 4, 2020

- Joker: Leaded Gas at the Oscars - February 7, 2020

- HBO’s Chernobyl: An Environmental History of the Invisible - August 27, 2019

- Climate Change and the Hockey Cultural Heritage Landscape - November 27, 2018