The holiday season has, for better and for worse, a lot of traditions. For many of us, that includes a Christmas tree.

The practice of decorating and lighting an evergreen at Christmastime is, of course, an invented tradition – one that, like a lot of our traditions, grew and thrived in Victorian Britain and her Canadian colonies.

But there is one tree – and one tradition – that is special for another reason. And to two particular cities.

This taps into an even older history, the sibling-esque relationship between New England and the Maritimes. There isn’t that much distance between Boston and Louisbourg (which Massachusetts troops besieged twice), or the Annapolis Valley (where Planters occupied Acadian lands), or Halifax (where HMS Shannon towed the captive USS Chesapeake), or the Gulf shore of Prince Edward Island (which saw fishing fleets from New England every summer).1 Generations of Maritimers migrated to the “Boston States,” and New Englanders began vacationing up north or back home.

But the closest pairing were the ports of Boston and Halifax, each founded as an Atlantic-facing entrepôt for British America and with world-class harbours.2

It was because of the harbour, though, that Halifax witnessed one of the greatest disasters in recorded history. On the morning of December 6, 1917, with the harbour crowded with wartime shipping, two ships collided in “the Narrows” before Bedford Basin. The Norwegian ship Imo struck the French Mont Blanc, which was loaded with benzol and TNT: “a floating bomb.”

There were a few helpless shouts. Then all movement and life about the ship were encompassed in a sound beyond hearing as the Mont Blanc opened up.

~ Hugh MacLennan, Barometer Rising (1941)

The combined shockwave and tidal wave destroyed much of the city’s north end, home to the naval dockyards, railway lines, shipping wharfs, and most of the working-class neighbourhoods. More than 1700 people were killed; hundreds were blinded by flying glass; 9000 were left homeless by either their houses collapsing or catching fire. And the next day, an early blizzard enveloped the city.

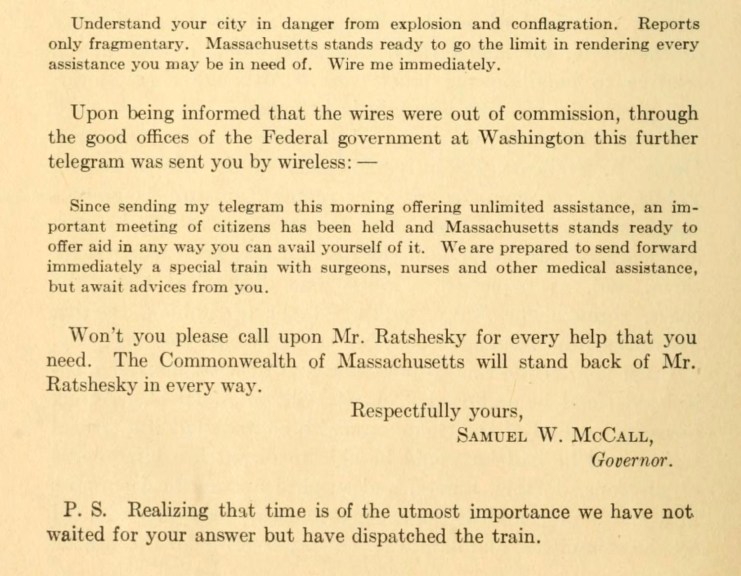

Within two hours, Boston knew. A telegram that morning from the Halifax branch of a Boston banking firm was rushed to the Massachusetts governor, who sent the wartime Massachusetts Committee on Public Safety into action. The first train, with two dozen doctors, nurses, Red Cross volunteers, and medical supplies, left that night, though hampered by snow and arriving to find the Halifax station destroyed. “I need hardly say to you that we have the strongest affection for the people of your city,” wrote Governor Samuel McCall to Halifax mayor Peter Martin, “and that we are anxious to do everything possible for their assistance at this time.”

The feeling was mutual. “Halifax, it is safe to say, will never forget the spontaneous and generous response of Massachusetts and the magnificent service rendered by our American friends in the hour of this city’s direst need,” wrote the Halifax Evening Mail on the first anniversary of the disaster. (Fred Pearson, chairman of the Halifax branch of the joint relief committee, and publisher of the Halifax Chronicle, was probably genuine, if a bit cringingly obsequious, in telling a Boston audience “how sincerely grateful we are, Nova Scotia, the Mouse, will not hesitate to tender its humble service to Massachusetts, the Lion.”) “It probably has done more to cement good relations and lasting friendship between the two countries than anything that has occurred in the past 140 years,” reflected the Boston Globe several months later.3

The Massachusetts-Halifax Relief Committee coordinated funds, supplies, and a major rebuilding project that lasted for years. (Indeed, the relief commission was not formally dissolved until 1976.) Jacob Remes has argued the Halifax explosion was not just “a part of our heritage” but a transnational event that drew on Progressive-era networks of relief professionals, planning experts, and goods and services.4

The two cities remained in close communication the following year; Nova Scotia sent nurses to Boston to help with its influenza epidemic, and Governor McCall visited his namesake housing project in Halifax that fall. McCall received an honorary degree from Dalhousie, but contrary to popular myth, there appears to be no record of a Christmas tree sent to Boston in thanks in the years immediately after the explosion.5

The idea for a “thank-you tree” actually came a half-century later. The Lunenburg County Christmas Tree Producers Association and the provincial government realized that here was a golden opportunity to market goodwill and a domestic product at the same time. The province had been exporting Christmas trees since the 1920s, but the sector grew dramatically by mid-century, and by the early 1970s Nova Scotia had also thrown itself enthusiastically into historically-inflected tourism promotion.6 (Although it took a few years for the province to trademark the Christmas tree; New Brunswick donated the tree for Boston in 1973, Quebec in 1974 and 1975.)

The memory of the Explosion is held deeply and gently in Halifax – bells chime on the mornings of December 6 from the crest of Fort Needham, across the Hydrostone houses built in the years afterward on the shale fragments. I lived three blocks from Massachusetts Avenue, one of several streets renamed for American aid. The event is both remote – like sepia photographs of putteed soldiers of the western front at Remembrance Day – and ever-present. The disaster occupies a psychological, architectural, and geological layer in the city; but it is the humanitarian response that is perennially retold, especially coming as it does at the beginning of the Christmas season.

But the thank-you tree, like a lot of things that we think of as “traditional,” is actually a pretty recent and pragmatic invention that has rapidly grown trappings of tradition. Responsibility for selecting and safeguarding a tree that satisfies expectations of size and symmetry falls to a “Christmas tree specialist,” and why did nobody tell me this job existed when I was eight. Cutting and sending the tree has grown into an annual ceremony, replete with piper (at the sending end) and town crier (at the receiving), now with its own Twitter account [for as long as that lasts ~ Ed.].

How is this a story of environmental history? Indeed, how is it not? An ancient, glacial harbour; an older history of coastal and cross-border geographies; a moment of petrochemicals and the explosives of modern warfare; the commerce of tree-farming; and the symbolism of a tree lit in the winter darkness. And a reminder that these histories, like the cities of Halifax and Boston, are intertwined. Amid the 1973 energy crisis, Boston, Ottawa, and other cities opted to reduce their electricity consumption by turning the Christmas lights off.7

Happy holidays, everyone.

Feature Image: From the @TreeforBoston account, November 2022.

Notes

1 The phrase is borrowed from Great Big Sea, but see work by George Rawlyk, Jeffers Lennox, Elizabeth Mancke, Edward MacDonald, Alan MacEachern, Brian Payne, Stephen Hornsby, and John Reid, among others.

2 See Pavla Simková, Urban Archipelago: An Environmental History of the Boston Harbor Islands (University of Massachusetts Press, 2021).

3 “The Devastated Area of Halifax as it appeared the day after the frightful explosion a year ago today,” Evening Mail, 6 December 1918; “Halifax Tenders Thanks,” Boston Post 13 March 1918 and “How Halifax relief is being Spent,” Boston Globe 13 March 1918; “Bay’s State Work on Halifax Relief,” Boston Globe 15 July 1918.

4 Jacob A.C. Remes, “‘Committed as Near Neighbors’: The Halifax Explosion and Border-Crossing People and Ideas,” American Review of Canadian Studies 45:1 (2015) 26-43. Of interest to environmental historians, he includes the International Boundary Commission and the International Joint Commission as like-organizations to the relief committee.

5 If anyone finds it, there are archivists in Halifax and Boston who would like to talk to you. My thanks especially to Rosemary Barbour in Halifax and Marta Crilly in Boston.

6 Indeed, almost a year to the day after the Explosion, the secretary of the Canadian Forestry Association suggested that four-fifths of Nova Scotia “is made by nature for growing tree crops and for no other job.” “Don’t longer neglect our forests and timber lands,” Halifax Evening Mail, 11 December 1918.

7 “City Orders Conservation,” Ottawa Journal 28 November 1973.

Latest posts by Claire Campbell (see all)

- Find the Flats: Or, the Cautionary Tale of Saint John West - January 5, 2026

- What Comes Next? The View from the Eighteenth Century - April 23, 2025

- Regional Plenaries at the 4th World Congress of Environmental History - May 9, 2024

- Made Ground: Urban Waterfronts as Anthropocene Relicts - April 26, 2024

- Call for Papers: Northeast and Atlantic Canada Environmental History (NEAR-EH) Workshop - February 29, 2024

- Cross-Country Check-Up on Climate Change - April 18, 2023

- Online Event – Eighteenth-Century Environmental Humanities - April 6, 2023

- CFP: Energy & the Environment, Association for Canadian Studies in the United States (ACSUS) - January 18, 2023

- Call for Papers – Backyard Natures: An Exploration of Local Environments in the Northeast - January 10, 2023

- The Thank-You Tree - December 20, 2022