This post is the third in our collaborative series with Histoire Source | Source Story about the “stuff” of environmental history. Check out the rest of the posts in the series here, and be sure to watch the Histoire Source | Source Story videos on the environmental histories of “outside.”

In part because of my family’s move to Pennsylvania nine years ago, and in part because of COVID’s forced proximity over the past two, I’ve been using local features –such as the rail-trail and canal routes – more often in my teaching. These, especially, invite us out of the classroom to get a nineteenth-century perspective on the post-industrial landscape.1 But the Susquehanna Valley isn’t where my heart or my research is, or where I’d like more of my teaching to be. For that, we have to go to another trail, a thousand miles east, back to the Maritimes.

The Confederation Trail lies along the bed of the Prince Edward Island Railway. The PEIR was begun in 1871, decommissioned by the Canadian National Railways in 1997, and converted as part of the TransCanada Trail by 2000.2 The trail is about 460 kilometres, even though the Island itself is only 280 kilometres from stem to stern: giving you a sense of the nonlinear and convoluted route – and endless political debate – of the line when it was built, slowly, in pieces, and expensively.

The rail-bed is different from the primary sources we usually associate with Confederation such as sepia photos of the Fathers on the steps of Province House and pages of Parliamentary rhetoric. But perhaps most directly, it’s a means of discussing the environmental agendas of Confederation.

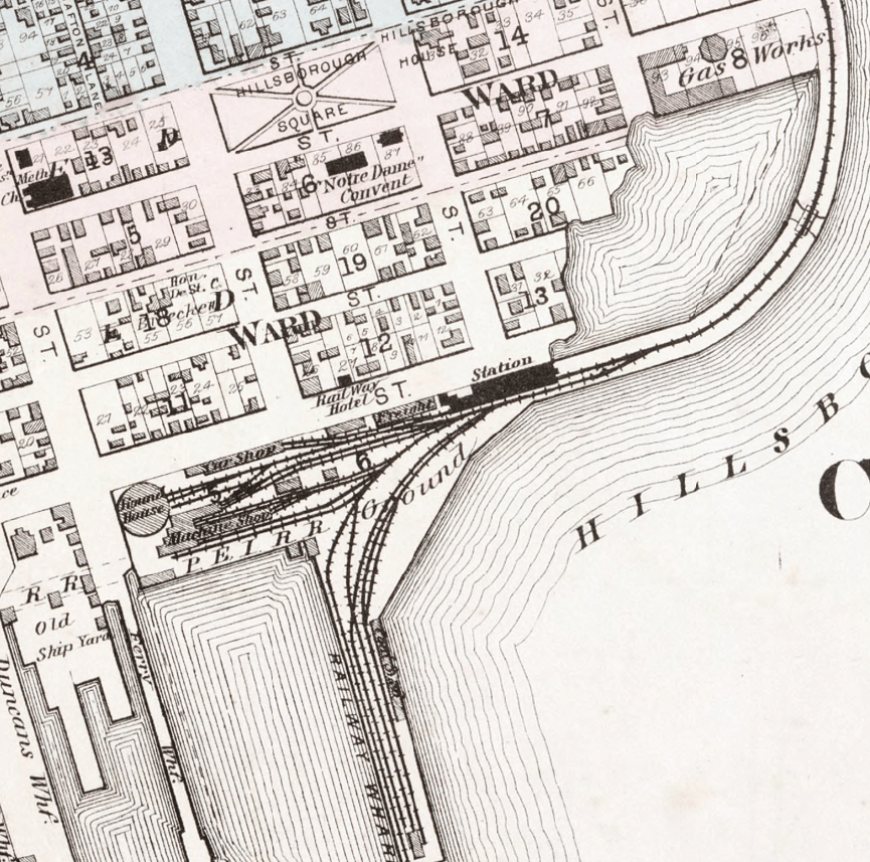

Let’s focus in on the couple of kilometres of trail that run through Charlottetown, the provincial capital.3 For one thing, they’re a useful complement to most streetscape heritage: durable and attractive, but often bought and paid for by the revenue or political capital from railway development.

They also remind us of the constitutional quandary of dividing jurisdiction in tidal, shoreline, and other imprecise places between three levels of government, as well as the federal footprint in Crown or federal land across the country.

The megaproject is a fundamental component of the Canadian nation-state. Our history can be read through a series of large, expensive, constructive projects that attempt to transform, most commonly, transportation or energy infrastructure, whether canals, seaways, railways, and highways, or pipelines or hydro-electric dams. The megaproject aligns with an ethos of nation-building, framed by the language of improvement, profitability, growth, and progress, moving, if not heaven and earth, at least one of them. “Lands appropriated for railway purposes” required drainage, infill, stream alignment, and displacement. Encircling all of this is the presence of fossil fuels, from coal yards to oil tanks to gas lines to electric wiring. So, while megaprojects are often mythologized and physically removed from where most of us live, the rail line in the city asks us to consider how the infrastructure of energy, or transportation, has made our neighbourhood in a much more immediate way.

A transportation corridor is a great opportunity for students to work with primary sources, especially maps, to read plans, property, and construction. The Island is especially lucky here, because of the outstanding archive at Island Imagined.4

But just as importantly, the trail offers the physical experience of a material, technological, and anachronistic landscape. Your corporeal self can occupy a space usually cast in greater-than-human (nation-building!) distances and (Superman!) speeds. At the same time, it makes areas that are usually cordoned off more accessible; you see back alleys and back walls, the unglamourous but functional machinery of urban growth, and its discards and tailings, without the heart-stopping Stand by Me moment of being caught behind an actual train. You begin to appreciate the expanse and weight of earlier decisions in shaping the landscape we inhabit; coal yards and oil tanks are still, probably, parking lots and oil tanks. What the trail can’t – and quite intentionally doesn’t want to – preserve is the sensory experience of sound and smell, but there is still plenty of scope for the imagination, as Anne of Green Gables would say.

The landscape is stuff. As Dale Barbour has said about his video entry in this series, “sometimes the best sources are the ones beneath your feet.” These are landscapes of reuse, or the landscape as palimpsest. Sequential Hillsborough Bridge(s); or the urban farm (the largest in Canada) on the grounds of the Experimental Farm, and across from a working farm: a chance to talk about urban/rural relationships, sustainable agriculture, and public/private lands.

And it is a story of restoration. Neither the trail nor the lands it passes through are, of course, “natural” – they have been raised and leveled, and are lined with species of disturbance such as birches and spruce – but there is space for nature. Just as the “anthropause” of COVID allowed wildlife to return to quieted streets, the trail offers space for mutual existence.

It offers a sliver of optimism, something we often struggle to find, for ourselves and our students in environmental history. Here our movement becomes part of the narrative, part of a reclaiming of space in cleaner, healthier, frankly more enjoyable ways. How might we restore, or inhabit, postindustrial landscapes? How can we make places more livable, for more people?

Yours might be on PEI, or it might be closer to home.

With gratitude to the collaborative forces behind Island Archives, especially Island Imagined: the Prince Edward Island Public Archives and Records Office, the Prince Edward Island Museum and Heritage Foundation, and the Robertson Library at the University of Prince Edward Island. And to Blair Stein for editorial guidance.

[1] I thank Ben Marsh (an historical geographer now retired from Bucknell) for this framing.

[2] For more on the context of this project, see Alan MacEachern and Edward MacDonald, The Summer Trade: A History of Tourism on Prince Edward Island (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2022), 224-225.

[3] The interpretative panels along the entire route have been digitized, with the Charlottetown section here: https://www.tourismpei.com/what-to-do/outdoor-activities/confederation-trail/confederation-trail-interpretive-panels#charlottetown

[4] Consider also the new story map from Joshua MacFadyen, Barbara Rousseau, and the UPEI GeoREACH Lab: “By Muscle, Mast, and Motor: A Transportation History of Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island.”

Latest posts by Claire Campbell (see all)

- Regional Plenaries at the 4th World Congress of Environmental History - May 9, 2024

- Made Ground: Urban Waterfronts as Anthropocene Relicts - April 26, 2024

- Call for Papers: Northeast and Atlantic Canada Environmental History (NEAR-EH) Workshop - February 29, 2024

- Cross-Country Check-Up on Climate Change - April 18, 2023

- Online Event – Eighteenth-Century Environmental Humanities - April 6, 2023

- CFP: Energy & the Environment, Association for Canadian Studies in the United States (ACSUS) - January 18, 2023

- Call for Papers – Backyard Natures: An Exploration of Local Environments in the Northeast - January 10, 2023

- The Thank-You Tree - December 20, 2022

- Stuff Stories: The Confederation Trail - July 18, 2022

- Summer Institute: Non/Humanity - April 1, 2022