Ann Shteir, ed. Flora’s Fieldworkers: Women and Botany in Nineteenth-Century Canada. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022.

The Royal Botanical Gardens in Burlington, Ontario, was the perfect place to launch Flora’s Fieldworkers: Women and Botany in Nineteenth-Century Canada (McGill-Queen’s UP 2022) on a recent beautiful October day. Contributors to this edited volume met to celebrate its publication and reflect on discussions that began in a workshop at York University five years earlier. We were an interdisciplinary crew of researchers coming together from women’s history, literary studies, botany, botanical history, the history of science, art history, garden history, and book history, and based in Ontario and Quebec as well as Scotland and Australia. Who, we asked, were the women active in botanical work and plant study of various kinds in 19th-century Canada? What are the gender and class dimensions of their stories? How did they come to know about plants? What were their contributions? What did their plant work mean to them? How do we find them, and where do we find material by them and about them?

These women “had opportunities through British colonial and imperial culture and society to work with plants and contribute to botanical knowledge.”

Flora’s Fieldworkers offers a plumb line into British practices of natural history that brought elite British sojourners and arrivals, settler-women of British background, and women born in Canada into botanical activities. There were manifold differences among them, of course, but as a cohort for study they had opportunities through British colonial and imperial culture and society to work with plants and contribute to botanical knowledge. Chapters in Flora’s Fieldworkers feature women who collected plants and reported about their findings; corresponded about plants with botanists and with botanical friends; wrote about plants and earned recognition, and money. Some drew, painted, and illustrated plants, and incorporated them in craftwork; taught about botany; and were active in organizations on behalf of knowledge of plants. Evidence of their enthusiasms is clear in the breadth and variety of their contributions.

Traill and Dalhousie

Catharine Parr Traill and Lady Dalhousie are the two women in the book who may have some current name-recognition for their botanical work: Traill because of her attention to plants and interest in Indigenous knowledge in The Backwoods of Canada (1836)and Canadian Wild Flowers (1868)and Lady Dalhousie (Christian Broun Ramsay) who botanized as a sojourner in British North America when her husband, George Ramsay, Lord Dalhousie, served as an imperial administrator during the 1820s-30s. Chapters in Flora’s Fieldworkers open new perspectives on both women and on what can be learned from their activities. Traill, for one, was caught in shifting crosscurrents of her time about what counted as “botanical knowledge,” who could claim it, and how to write about it for different audiences in 19th century science and society. She was aware of these crosscurrents herself, and her work opens out to fresh study as a result. Michael Peterman’s chapter in Flora’s Fieldworkers uses Traill’s letters to explore her publishing career as a natural history writer, and especially brings attention to her less known late work, Studies of Plant Life in Canada (1884).

Lady Dalhousie, an elite woman and fervent and self-taught student of botany, collected plants in Nova Scotia and Quebec, and later in India, and worked to create the first botanical garden in Canada. Chapters by garden historian Deborah Reid and post-colonial historian Virginia Vandenberg use previously unstudied materials to trace public and private aspects of Lady Dalhousie’s botanical journeys during her years as one of Flora’s fieldworkers. Plants she collected in British North America and in India are held in numerous locations, including at the Royal Botanical Gardens, and the chapter by botanist and botanical historian Jacques Cayouette shows the value that historical material like hers can have for practices now. Cayouette used herbaria specimens, plant lists, albums, and other archival sources to compile data about the location and first recorded collection of orchids and other rare plants that Lady Dalhousie found in Lower Canada during the 1820s, and agencies in Quebec apply this botanical information toward plant protection and conservation work.

Discovery and Re-Discovery

Flora’s Fieldworkers is a book about discovery: following up a name in a list of members, finding the women, filling in a sketchy story. Chapters report on research that benefitted from archivists, curators, librarians, and family members and also from digitization projects that have opened access to resources in so many new ways. Archivists in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, for example, helped me reconstruct how the Halifax-born daughter of the colonial elite came to collect plants in Newfoundland during the early 1830s for British botanist William Jackson Hooker’s Flora Boreali-Americana.

Australian historian of science Sara Maroske had digital access to 19th-century newspapers and magazines as her path to reconstructing botanical work by more than 200 women in Australia who collected plants for a Flora of that part of the British Empire. Botanist and botanical historian James Pringle was alerted to material in the herbarium at the University of Guelph that led him, similarly, to reconstruct contributions by Alice Hollingworth to knowledge of plants in the Muskoka District of Ontario during the 1890s. His research enters Alice Hollingworth, “a name unfamiliar to historians of botany” into the literature of botanical history, and also opens a window onto the life and work of a previously unstudied late 19th century Canadian plant collector. Daughter of a pioneer family involved in scientific pursuits and organizations, Hollingworth was active in botanical exchange work and in later years promoted the use of native species in home landscaping in lectures at Farmers’ Institutes and the Women’s Institutes. The range of her plant-related activities invites further study.

“Flora’s Fieldworkers looks beyond “the usual records” and calls upon a variety of critical tools to foreground botanical activities by women and make these histories more visible and audible.”

Flora’s Fieldworkers is a book about both discovery and re-discovery. I learned through my own research in British botanical culture that some of the women I thought I was “discovering” for their activities as collectors, writers, artists, and teachers were acknowledged in their own day, and that it is we who have not known about them because they did not figure in historical records. Flora’s Fieldworkers looks beyond “the usual records” and calls upon a variety of critical tools to foreground botanical activities by women and make these histories more visible and audible. In addition, it is a call for others to research Flora’s fieldworkers in diverse communities and traditions beyond those that were the focus of our volume.

The Visual and Material

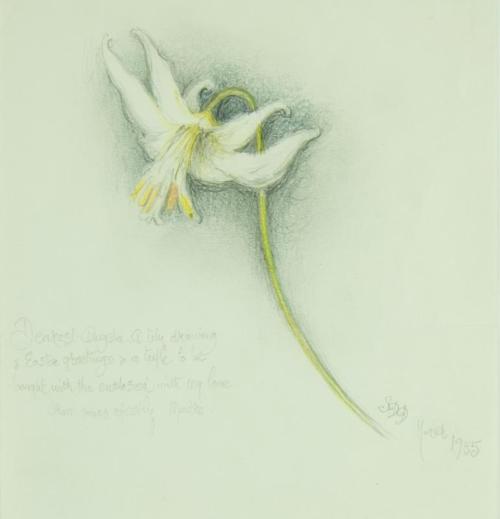

Chapters in Flora’s Fieldworkers explore visual and material aspects of women’s plant work in 19th century Canada as well. Art historian Kristina Huneault has studied two late-century botanical albums put together by Sophie Pemberton in British Columbia. Reading them through a complex and layered gendered lens, Huneault finds a woman artist struggling with issues of identity by working both within and against conventions of botanical illustration. Vanessa Nicholas, a historian of Canadian craft and decorative work, researched plant motifs on two heritage quilts made by settler-women in mid-century Ontario and found rich material for cultural analysis. Her chapter explores, for example, images of trilliums and other wildflowers on one quilt that suggest both the quilter’s British floral heritage and a connection to her new home in Canada, and floral design elements on another quilt that point to beadwork traditions and floral motifs associated with Woodlands Indigenous Peoples. Karen Stanworth, a historian of education in 19th century Canada, was led by her interest in pedagogy and visual materials to Isabella McIntosh in 1860s Montreal who collected ferns and brought botany into the curriculum of her girls’ school. Stanworth’s chapter locates this work in relation to mid-century activities in natural history in Montreal and the development of natural history teaching at McGill University.

“…the shifting terrains in “ways of knowing” [during the 19th century] shaped which topics and activities carried value and how contributions would be recorded, or not.”

In the Afterword to Flora’s Fieldworkers, Suzanne Zeller reflects from the perspective of the history of science on efforts in Flora’s Fieldworkers “to recover the historical voices of botany’s gendered – and all too often anonymous – understory.” Seeking meaning in that understory, she calls upon the three “ways of knowing” in 19th-century science – natural historical, analytic, and experimental — that John Pickstone charted in his New History of Science, Technology and Medicine (2000). Zeller reads chapters in Flora’s Fieldworkers chronologically in relation to the displacement of natural history ways of knowing early in the century by analytical approaches and then by experimentalist ways that put their stamp on practices in botany and other sciences later on. This is an apt way to think about women’s activities within cultures of nature and science in 19th-century Canada because the shifting terrains in “ways of knowing” shaped which topics and activities carried value and how contributions would be recorded, or not.

Zeller chose a passage from The Overstory (2018), the ecological novel by Richard Powers, as the epigram for her Afterword: “The tree is saying things, in words before words … If your mind were only a slightly greener thing, we’d drown you in meaning.” I can imagine that Catharine Parr Traill in 19th-century Ontario would have welcomed this quotation for her own work on plants within the changing botanical cultures of her time.