This is the thirteenth post in the series, Succession II: Queering the Environment, a fourteen-part series in which contributors explore topics related to unruliness, care, and pleasure. Succession II centers queer people, non-humans, systems, and ideas and explores their impact within the fields of environmental history, environmental humanities, and queer ecology.

Kyla Wazana Tompkins writes that “eating is often a site of erotic pleasure itself,” one that signals an “alignment between oral pleasure and other forms of nonnormative desire.”1 This form of political agency she coins queer alimentarity, and with it frames ingestion, and even indigestion (or, the refusal to be easily incorporated) as potentially disruptive to white racial and colonial hegemony. As we will come to argue, veganism — that is, the collection of dietary habits and other practices that aim to divest from violent consumption — can also function as a site of disruption and pleasure.

Our framing of veganism is in part due to its long association with queer orientations and food traditions. In her work on vegetarian feminist restaurants in the US and Canada, Alex Ketchum notes that many of these spaces were “owned by a collective of lesbians” and revolved around vegetarian ethics, labour issues, cost, and sourcing of products that challenged the status quo around cooking and consumption.2 In addition, as Rasmus Simonsen argues, veganism has functioned in these contexts as “a way of resisting heteronormativity, since meat-eating … is tied to the rhetorical as well as the actual reproduction of heterosexual norms and practices.”3 Where meat is symbolic of power, strength, affluence, and virility, particularly in colonial contexts, vegetal foods can be legible as queer disruptions of normative logics associated with food’s social and cultural positioning. Given “vegan food’s ability to trouble established food categories,”4 vegan practices — such as the consumption of vegan foods — can function as a kind of queer alimentarity, aligning the wish to eat plants in meat-centered places with non-normative desire.

Critical veganism is a model of speculative possibility: it makes real an imagined world of multispecies kinship beyond the structuring logics of capitalism and white supremacy in ways that are inherently queer.

Not all veganism carries the same transformative potential, however. Mainstream white veganism, for example, is focused “almost exclusively around questions of food” and “is uncoupled and detached from related actions relevant to interspecies social justice.”5 At the same time, mainstream white veganism is “very much endorsed and promoted by corporate interests and investment,”6 such that, in this context, eating vegan food comes to mean performing a kind of consumerism that is considered good or moral.7 Indeed, the conflation of veganism with moral eating emphasizes the ways that veganism has been couched in diet culture’s “clean eating” discourse which, as food studies scholar Sabrina Strings has traced, is rooted in anti-Blackness and white supremacy8. In addition, many white vegans often deploy veganism as a tool to both enable and justify ongoing settler colonialism in so-called Canada (and elsewhere). The moral underpinnings of veganism are thus used as justification for the enactment of anti-Indigenous laws and policy that include condemning and limiting Indigenous’ peoples access to food, land, and waters in ways that (re)justify the ongoing dispossession, displacement, and genocide against Indigenous people.

While mainstream white veganism has accrued some level of popularity, critical veganisms that are rooted in anti-racist and anti-colonial logics are often dismissed by the (largely white) mainstream as unpalatable. As Carol J. Adams writes, in a context where meat, even expensive meat alternatives, are “something one enjoys,” vegetal foods become “representative of someone who does not enjoy anything: a person who leads a monotonous, passive, or merely physical existence.”9 This assertion resonates with Ahmed’s work on the killjoy, a figure that brings into view the violences enacted by dominant configurations of power but, by so doing, becomes “the object of shared disapproval.”10 For both Adams and Ahmed, the table is where fraught encounters happen, further clinching the act of eating as one charged both with contention, but also, as we suggest, the pleasures of speculative possibility.

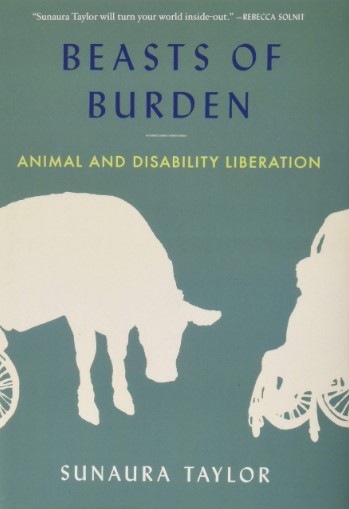

As such, following thinkers like Sunaura Taylor, Margaret Robinson, Aph Ko, and A. Breeze Harper, we here use the term veganism as a shorthand for what we understand as critical vegan praxis: a veganism that at once seeks “to exclude—as far as is possible and practicable—all forms of exploitation of, and cruelty to, animals for food, clothing or any other purpose”11 and functions as “a critical intervention into race, power, animality, and thought”12 while framing “animal issues as profoundly relevant and even essential to other social justice issues.”13 Thus, our consideration of queer vegan pleasure is informed by these interventions, and aims to participate in ongoing projects working to disentangle veganism from institutions that structuralize and normalize the interests, experiences, and embodiment of predominantly white people, including white queers.

Working from our positions as white settlers within the academy, and in solidarity with ongoing anti-colonial projects, we imagine critical vegan praxis as part of what Sara Ahmed has called a “double turn”14: a turning towards the ways we are and remain implicated in how veganism often functions as a tool of whiteness, while also orienting towards the multispecies relations of care that are possible beyond hegemonic structures of power. Keeping in mind Cree scholar and writer Billy-Ray Belcourt’s contention that “we cannot address animal oppression and liberation without beginning from an understanding that settler colonialism and white supremacy are the bedrock of much of the structural violence that unfolds on occupied Indigenous territory”15 and that a majority of critical scholarship on the more-than-human and veganism from settlers is done “in a way that neither attends to the large body of writing in Indigenous studies about other-than-human life nor calls for both the abolition of the settler state and a repatriation of land to Indigenous communities,”16 we conceptualize critical vegan praxis as more than just a theoretical intervention. For us, critical vegan praxis works to constitute “acts of solidarity”17 with those marginalized by hegemonic systems, including Black, Indigenous, and people of colour, trans, queer, and disabled people, as well as kin beyond species, like animals, plants, and planet.

Work by Sunaura Taylor (far left), Aph Ko and Syl Ko (center left), A. Breeze Harper (center right), and Billy-Ray Belcourt and Margaret Robinson (included in the volume, Colonialism and Animality (far right)) inspire the authors’ commitment to critical vegan praxis as a queer politics of solidarity.

Orienting towards a critical veganism, that is, towards better forms of relating to/with beings with whom we share space, is to redirect our attention towards different expressions and experiences of embodied pleasure that may be called “deviant” or queer.18 Queerness and pleasure have already been taken up as sites of political resistance, and we owe our thinking here particularly to the Black women who have seen and expressed the potentialities at these intersections. For example, in Pleasure Activism, adrienne maree brown writes: “What a pleasure it is, after all, to be a free Black queer woman … To be of the earth, with such beauty and interconnectedness.”19Furthermore, Audre Lorde might attribute Tompkins’s queer alimentarity, in part, to “the power of the erotic,” the expression of which is tied to the joy and fulfillment of desires denied, but that once realized, can give “the energy to pursue genuine change in our world.”20 By reading these three together, brown’s, Tompkins’ and Lorde’s work bind queerness, joy, and eating, suggesting the revolutionary possibility of joyful queer eating practices such as a critical veganism.

As Adams puts it, by eating differently, vegans might destroy “the pleasure of meals as we now know [them]. But what awaits us is the discovery of the pleasure of vegan meals.”21 Indeed, the pleasure of vegan meals lies not only in the meals themselves, but also in the discovery, or, in other words, in pursuing and consummating desire. There is a uniquely vegan joy in managing to (re)create a favourite dish from childhood without animal products, or in coming across an actually-tasty vegan cheese.

Critical vegan praxis works to constitute “acts of solidarity” with those marginalized by hegemonic systems, including Black, Indigenous, and people of colour, trans, queer, and disabled people, as well as kin beyond species, like animals, plants, and planet.

But the speculative possibilities of critical vegan praxis also extend beyond these culinary pleasures. Engaging in critical veganism is one method of imagining otherwise and is therefore also a process that requires certain kinds of participation in what Adams calls “engaged theory,” that is, “theory that arises from anger at what is” while “envisioning what is possible.”22 In this way, engaging in/with critical vegan praxis practices a kind of prefigurative queer politics, where “living in accord with one’s political vision is a way of laying the foundations for the world we want to see.”23 As such, this engaged theory—this embodied politic that is critical veganism—is itself a model of speculative possibility: it makes real an imagined world of multispecies kinship beyond the structuring logics of capitalism and white supremacy in ways that are inherently queer.

In short, queer vegan pleasure is not simply about divesting from meat or reimagining the options at the grocery store. It is not about reproducing consumer patterns that continue to extract from people, animals, and planet. Instead, critical veganism can be a queerly pleasurable process of lusting and loving after flavours and textures, and recalling, adapting, or making new relations and worlds in a mode of care.

Notes

- Kyla Wazana Tompkins, Racial Indigestion: Eating Bodies in the Nineteenth Century (New York: New York University Press, 2012), 5.

- Alex Ketchum, “Counter Culture: The Making of Feminist Food in Feminist Restaurants, Cafes, and Coffeehouses,” Cuizine: The Journal of Canadian Food Cultures 7, no. 2 (2016), DOI: 10.7202/1038477ar.

- Rasmus R. Simonsen, “A Queer Vegan Manifesto,” Journal for Critical Animal Studies 10, no. 3 (2012): 55, https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/acwp_aafhh/8/.

- A. Paige Frazier, “Drag Cuisines: The Inherent Queerness of Vegan Food Ontologies,” Succession: Queering the Environment—A NiCHE Series, (2020), https://niche-canada.org/2020/06/16/drag-cuisines-the-inherent-queerness-of-vegan-food-ontologies/.

- Richard White, “Looking Backward/ Moving Forward. Articulating a “Yes, BUT…!” Response to Lifestyle Veganism, and Outlining Post-Capitalist Futures in Critical Veganic Agriculture,” EuropeNow 20, (2018): 4, http://shura.shu.ac.uk/22661/.

- White, 4.

- For more context on the ways that veganism might come to be understood in white settler cultures as moral, see Melissa Montanari, “Mainstream Vegan’s Appropriation Problem: Close Reading Morality in Vegan Narratives,” in Food Studies: Matter, Meaning & Movement, eds. D. Szanto, A. Di Battista, and I. Knezevic (Ottawa: Food Studies Press, 2022). For more information on the history of veganism in the contemporary American context, as well as the way it is implicated in diet culture, see Laura Wright, The Vegan Studies Project: Food, Animals, and Gender in the Age of Terror (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2015).

- Sabrina Strings, Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia (New York: New York University Press, 2019).

- Carol J. Adams, The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory (New York: Continuum, 2010), 61.

- Sara Ahmed, “Feminist Killjoys (And Other Willful Subjects),” Polyphonic Feminisms: Acting in Concert 8, no. 3 (2010).

- The Vegan Society, “Definition of Veganism,” The Vegan Society, accessed May 5 2022, https://www.vegansociety.com/go-vegan/definition-veganism.

- Aph Ko, Racism as Zoological Witchcraft: A Guide to Getting Out (Brooklyn: Lantern Books, 2019).

- Sunaura Taylor, Beasts of Burden: Animal and Disability Liberation (New York: The New Press, 2017), xv.

- Sara Ahmed, “Declarations of Whiteness: The Non-Performativity of Anti-Racism,” Borderlands 3, no. 2 (2004), https://rbb85.wordpress.com/2014/08/24/declarations-of-whiteness/

- Billy-Ray Belcourt, “An Indigenous Critique of Critical Animal Studies,” in Colonialism and Animality: Anti-Colonial Perspectives in Critical Animal Studies, eds. Kelly Struthers Montford & Chloë Taylor (New York: Routledge, 2020), 21.

- Belcourt, 20.

- Alasdair Cochrane and Mara-Daria Cojocaru, “Veganism as Political Solidarity: Beyond ‘Ethical Veganism’,” Journal of Social Philosophy (2022): 2, DOI: 10.1111/josp.12460.

- Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), 2.

- adrienne maree brown, Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good (Chico, CA: AK Press, 2019).

- Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Berkeley: Crossing Press, 2007).

- Adams, 243.

- Adams, 2.

- Jason Mark, “Yes, Actually, Individual Responsibility Is Essential to Solving the Climate Crisis,” Sierra, (2019), https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/yes-actually-individual-responsibility-essential-solving-climate-crisis.

Featured image: Photo by Julia Zolotova on Unsplash.

Marika Avenel Brown & Melissa Montanari

Latest posts by Marika Avenel Brown & Melissa Montanari (see all)

- On the Possibilities of Queer Vegan Pleasure - June 29, 2022