Editor’s Note: This is the first of two posts in which freelance researcher David Brownstein responds to the ongoing Fairy Creek protests by reflecting on the long history of logging protests in B.C. Part two will run on January 14, 2022.

With BC logging protests and an old-growth logging moratorium much in the news, this is an ideal time to survey the surprisingly long history of such conflicts. No matter your stance on these issues, we can all benefit from understanding how past choices constrain present action (and how present choices will similarly constrain the choices of future generations). My hope is that familiarity with this history might inform current forest-policy debates.

I begin with a recent, infamous photo, before sharing context and analysis for six early logging controversies (1899-1944). Four of these cases are published here today, with another two cases plus historical/contemporary comparison and conclusions to appear on the NiCHE blog in January, 2022.

Lorna Beecroft’s photo is a perfect juxtaposition. Coastal mega-flora on a truck, and spaghetti-sized second-growth obscuring the left horizon. Back on May 25th, Beecroft was driving on the Nanaimo Parkway, doing a 9am grocery run. She couldn’t believe what she saw. “How old is this tree, and how did it end up on this truck?” She thought it so remarkable, given the context of the ongoing old-growth Fairy Creek watershed protests, that she captured a photo for social media.

At the time, nobody knew the log’s story and an accusatory search was on. Who felled this giant tree? Who was to blame?! The online anger was immediate. “Barbaric” was a common theme, and those pronouncing anger were seemingly united in a rejection of the future, now present, so carefully planned for us by our predecessors.

The last century of forest management is now coming under the same scrutiny as other elements of colonization and past province-building. There is already a small library on evolving logging technologies, including logs on trucks.1 Here, I’d like to focus on the other half of Beecroft’s photo, the invisible propellant that fuelled her viral image’s internet travels. Despite many scattered mentions in the forest-history literature, nobody has yet synthesized a comprehensive account of BC logging protests.2 Yet twentieth-century feats of logging engineering were parallelled by a range of controversies. Beecroft’s photo and the conversation surrounding the current old-growth protests represent a continuity of long disagreements.

What unites most past controversies is that both the federal and provincial Crown allocated logging rights before contemplation of other important values. The advance sale earned public revenue, but it also made those rights expensive to re-acquire when the public decided that those rights were more valuable unexercised, or, as is increasingly understood, if Indigenous land title was not the Crown’s to sell. The federal and provincial governments retained control of the land base as Crown lands; however, they sold or leased the rights to the trees on that land in such a way that those rights became semi-permanent. This happened for good reasons–-investors sought certainty to inform long-term decisions. However, with the passage of time these semi-permanent, now transferable logging rights also became more valuable (a trend anticipated as early as 1910). Logging rights were transformed into an asset. Therefore, when the public subsequently contested some sales via anti-logging protests, a heavy financial burden emerged. The government was obliged to compensate private capital for its lost asset value, a burden ultimately borne by taxpayers.

And, perhaps most importantly, extinguishing existing logging rights has always been terribly expensive, a cost ultimately born by provincial taxpayers.

Lorna Beecroft’s viral photo is but a recent statement in this longstanding conversation. Through a study of six cases we can identify several other enduring themes that connect past logging controversies to those of the present. Historical actors, as now, feared that future generations would never see old growth trees. The fate of old growth, then as now, was an emotionally fraught topic, which polarized communities and sometimes devolved into violence. The press was consistently used to advance claims and inform policy debates, by both British Columbians and outsiders, who were equally passionate about forest policy. And, perhaps most importantly, extinguishing existing logging rights has always been terribly expensive, a cost ultimately born by provincial taxpayers.

1) Deadman’s Island Protest, Vancouver, 1899-1917

The Deadman’s Island logging controversy predates the truck era. Deadman’s Island is also the only one of our six cases in which the controversy unfolded on the actual site of the intended logging. As such, it is the only case to boast a physical “protest.” This episode quickly arose when government, without broad public support, granted a company permission to remove trees.3

Deadman’s Island, just adjacent to the current Stanley Park, was previously known to the Squamish as skwtsa7s, and used for Indigenous tree-burial.4 Settlers, too, used the island as a cemetery until 1887, and later as a quarantine site for disease victims. In an 1863 survey, the island was included as part of a colonial military reserve, and thus, after B.C. joined Confederation in 1871, Deadman’s Island was subsequently claimed under federal government jurisdiction. Despite this assertion, both the Vancouver Parks Board and locals who lived in the adjacent, wealthy West End viewed the island as part of the city park. Thus the stage was set for significant conflict when, in 1899, the federal Minister of Militia and Defence leased the island to Ontario-born industrialist Theodore Ludgate, with an allowance to clear the trees and build a sawmill.5

The next 13 years saw what I would like to call the start-and-stop “lurch-logging” characteristic of several B.C. protests involving trees. By this, I mean that within an atmosphere of high drama, the courts were used to push contradictory agendas to allow, or disallow, logging. As we shall see in later cases, sometimes the mere threat of logging was used as a strategy to force a resolution, with tree-cutting not necessarily being the actual goal.

As we shall see in later cases, sometimes the mere threat of logging was used as a strategy to force a resolution, with tree-cutting not necessarily being the actual goal.

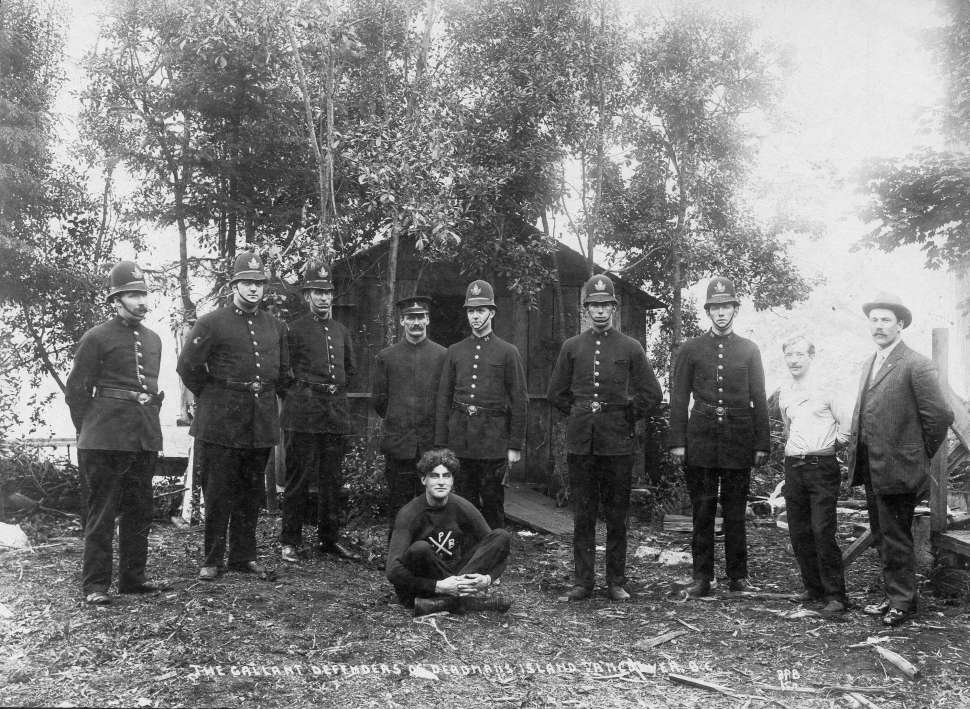

In the Deadman’s Island case, on the one hand, there was an out-of-town businessman, supported by a throng of workers who lived on Vancouver’s east side, keen for the wealth that mill jobs would bring. On the other, there was a collection of rich and powerful urbanites who wanted to retain the beauty of treed surroundings for recreation and leisure. A glance at Figure 2, above, gives quick insight into what they sought to protect and retain.

At different points in the Deadman’s Island conflict, and despite internal disagreement at each level, all three governments (municipal, provincial and federal) claimed authority over the island, and thus deemed themselves the ultimate arbiter of appropriate land use, including logging’s permissibility. Indeed, with a high drama show of force, the municipality prevented Ludgate’s attempted logging on 24 April, 1899.6 The province cooperated with the municipality to frustrate a second logging attempt on May 15th.7

During this latter episode, there was a charged physical confrontation between police and intended loggers reminiscent of what we see at Fairy Creek (though in this historical case, roles were reversed, with the provincial state opposed to tree-felling). For Ludgate’s attempts to direct his men to log, he was wrestled to the ground by three police officers:

…Mr Ludgate struggled to free himself and that made the officers only tighten their holds. They struggled more fiercely, and as all three are heavily built men, the exhibition was one that would create a sensation in any arena. Gradually Mr Ludgate was pushed backwards to the ground and the handcuffs put in place. He still struggled and resisted, but when the Riot act was read a few moments later, Mr Ludgate submitted and walked unaided to the carriage. During the enactment of these operations there was almost perfect silence on the part of the men. Magistrate Anderson read the Riot act to them twice and told them plainly the consequences of any further action on their part … a little over three hours work had made quite a hole in the trees…8

The next years saw back and forth court battles, episodes of tree-felling, as well as additional 1909 physical altercations, including sticks, clubs, drawn guns and jail-time, culminating in the island being cleared of both trees and squatters. Figure 3 captures some of these tensions in heroic form, with police being “The Gallant Defenders” of the island’s trees. In the end, few were satisfied. Ludgate died at Camp Borden, Ontario on February 10, 1917, without ever having built his mill. The workers in the city’s East never realized their dreams of well-compensated mill jobs, while residents of Vancouver’s tony West End were disappointed to have lost the Island’s trees. The island was officially returned to municipal control in 1929, but Depression-era lack-of-funds prevented the city from redeveloping the Island back into a park. In the Second World War, the Island was returned to military control, becoming the HMCS Discovery naval station, a training base. With comparatively few trees, it has remained such ever since.

2) Green Timbers, Surrey, 1912-27

The Lower Mainland hosted logging for the international market since the 1860s. By the 1910s, however, the end of the local big-trees was in sight. The trees at Green Timbers represented some of the last of that local, accessible old-growth.

Green Timbers was located away from the waterways that hosted most Indigenous pre-contact settlements, with no known permanent settlements in what is today north Surrey. However, the broader area saw intersections in traditional territories of the Kwantlen, Katzie, Tsawwassen and WSANEC First Nations. Notably, the Kwantlen had established Kitkait, on the south side of the Fraser River, six kilometres from the heart of the Green Timbers Forest.9 After contact, Green Timbers was also part of the federally managed “Railway Belt,” located on either side of the Canadian Pacific Railway. As we shall see in this case, federal, rather than provincial, management gave loggers an advantage when negotiating with tourism boosters bent on keeping the trees standing. In common with the previous Deadman’s Island conflict, these federally managed trees would also be logged.

In 1912, The Vancouver Board of Trade proposed a park on the Pacific Highway in Surrey, with the Surrey Board of Trade echoing the call a year later. In time they would be joined by the Good Roads League of British Columbia. All three booster organizations realized that Green Timbers was the last remaining stand of old-growth in the lower Fraser Valley. It was attracting increasing numbers of visitors –- visitors with potential money to spend.10

This case pitted prominent officials against local loggers. Some of the officials lived in Surrey but most were from elsewhere in the Lower Mainland. By 1920, these boosters’ approach was to turn this forest (and the subject of a below case, the Cameron Lake timber, aka Cathedral Grove) into a First World War memorial for fallen soldiers. This preservation strategy, while interesting, was not successful. As the controversy dragged on, in 1923 international foresters visiting with the British Empire Forestry conference joined the fray, and they were also opposed to logging Green Timbers. Delegates from both the UK and South Africa were horrified by the thought that trees that had taken more than two hundred years to grow, now on either side of the Vancouver-San Francisco highway, might be logged. They felt the trees were an asset not only to British Columbia, but to the world.11 In this regard, the Green Timbers controversy differs from those that rage today. Opposition to this historical logging was not necessarily widespread across the public. Rather, a small group of people saw an imminent future in which the trees’ scarcity would increase their value. Their concern was not necessarily shared.

This second case introduced a new mechanism to defuse future logging conflicts: cash payments to extinguish logging rights, as well as land swap for rights elsewhere. In 1922, Bruce M. Farris, co-owner of the logging rights, had offered to sell the lease back to the federal government, but the $350,000 asking price was thought exorbitant. Despite mounting pressure from both select locals and prominent visitors, the province argued that Green Timbers’ logging (or not) was a matter for the federal government.12

In his fine thesis, Sandquist details frantic behind-the-scenes negotiations brokered by noteworthy, highly-placed individuals to prevent logging at Green Timbers. The negotiations’ many twists must have felt like an amusement-park ride, though they exceed what might be communicated in an already too-long blog entry. Ultimately, leaseholder M.B. King demanded $250,000 in cash, in addition to an exchange representing cutting rights to 250 million feet of timber elsewhere. At a time during which the federal government was navigating the King-Byng constitutional crisis, with little attention to spare for a local dispute, the logger’s terms exceeded what the federal government was willing to pay. This case differed from that of Deadman’s Island in that here, the federal crown supported the trees’ protection. However, the price of doing so was simply too high. The passionate professors and bureaucrats had been unsuccessful in capturing the public imagination –- the trees were felled, beginning on May 8, 1927. The last tree came down at noon on 28 August 1930, in front of a ceremonial gathering of provincial forestry officials.13

There was an expression of sadness among the small knot of visitors who witnessed the sawing odf [sic] the last of these stately and massive timbers which formed one of the noted tourist attractions on the North American continent.14

Soon after, and of little comfort to the “protestors” in this case, the logged lands would become the site of an extensive provincial forest nursery, growing seedlings to reforest logged lands elsewhere. Green Timbers would have an equal impact, however, as a powerful name, frequently invoked by those opposed to logging as a cautionary tale in subsequent disputes.

3) Seymour and Capilano Watersheds, West Vancouver, 1923-1933

Vancouver’s North shore is another instance in which the government disbursed timber rights in advance of contemplating the wider public interests. This time, however, the focus of the protest was different. Rather than recreation or tourism, the compelling issue was human health.

Home of the Squamish, Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh peoples, the Capilano River became a source of drinking water for Vancouver in 1889. While municipal governments owned the pipes, they did not acquire control of the broader Capilano and Seymour watersheds. Furthermore, they could not afford to buy that control, because the province had previously sold a range of rights to competing land-users such as homesteaders, miners and timber companies. Alienation of these rights gave rise to a conflict between logging and public health, or what might be recognized today as ecosystem services.

The Greater Vancouver Water Board was concerned that the loggers would introduce disease into the streams destined for Vancouver taps. Near the end of the First World War, provincial officials drew up regulations under BC’s Health Act, which applied to anyone travelling through the watersheds. People were required to carry documentation that their vaccinations were current, and that their blood had been tested to ensure that they were not carriers of typhoid fever, diphtheria, or venereal disease.15

Through the mid-1920s, there was a fierce local debate as to whether logging was compatible with the provision of drinking water. The provincial government used logging royalties to pay for public services. Understandably, the province was keen to continue logging. The Water Commissioner, and local groups such as the Vancouver Natural History Society, wanted the logging to stop. To complicate matters, yet others wanted to use the logging railroads as the basis for a renewed route through the mountains to Squamish and beyond.16

In anticipation of a 16 June 1923 municipal plebiscite to decide whether taxpayers would approve the expenditure to acquire the logging leases on Burrard Inlet’s north shore, University of British Columbia botany professor John Davidson “made a study of the effect of timber removal on [drinking] water supply.” He thought that the slopes of the Seymour Valley should not be logged, and as a further reason for preserving the forest, Davidson felt the threat of fire in the logged waste was too great.17 The bylaw passed, but it did not meet the required three-fifths majority to spend $350,000 to secure the privately-owned timber rights. Nine out of 12 districts had voted in favour, prompting lease-holder W.F. Bickel to observe that given such widespread support, he would not move to log the trees until the money bylaw, based on his offer, had been disposed of by the ratepayers.18

On 1 October 1924, Davidson delivered an annual Presidential address before the 300-member Natural History Society entitled, “The Handwriting on the Wall or Wake Up! Vancouver (an address on the conservation of plant life).” One-thousand copies of the speech were printed and circulated to incredible effect, eliciting a loud response from both public (opposed to logging) and the provincial government (in favour). This whipping up of negative public sentiment was little different from the methods used today, with the only element to distinguish one strategy from the other being form (the printed word vs social media). Vancouver editorialists tended to agree with the Natural Historians, rather than government assurances, describing B.C. forests as an asset of ‘untold value’ that should be ‘intelligently utilized’ and demanding that ‘a vigorous reforestation policy should be put forward at the next session of the House at Victoria.’19

On 1 October 1924, Davidson delivered an annual Presidential address before the 300-member Natural History Society entitled, “The Handwriting on the Wall or Wake Up! Vancouver (an address on the conservation of plant life).”

Ultimately, those trees not yet logged would remain standing. In this case, the weight of public health had achieved what recreation and tourist potential had failed to accomplish for Green Timbers. Further, the natural historians’ concentrated conservation efforts, bolstered by municipal bureaucrats’ advocacy and pressure in the press, prompted a reluctant provincial intervention. The Greater Vancouver Water District was created by provincial legislation in 1926. By November 1933, the last log to be felled was cut from the Capilano watershed. In subsequent decades, additional controversies would arise when all human presence would be banned from the watershed lands that supplied Metro Vancouver with drinking water.20

4) Strathcona Park, Vancouver Island, 1926-1943

In another case of competing values, and reminiscent of the Green Timbers controversy, a significant section of the public found itself opposed to its own government. And here, again, the forest products economy was in opposition to tourism and recreation. Alarmed by the rate of logging on Vancouver Island, in 1905, the Victoria-based Natural History Society of British Columbia lobbied for a provincial park to preserve scenic parcels of land for future generations. They were joined by the Victoria Board of Trade (indeed, the two groups shared some common members).21 We might contrast these groups with those people who opposed the Green Timbers logging. Here were organizations that each represented a large constituency, coordinated groups of people, rather than lone individuals.

The first choice for a park was the timber on Cameron Lake, but both land, and thus logging rights, was then owned by the Victoria Lumber and Manufacturing Company, much too expensive for taxpayers to acquire. The eventual Strathcona Park, located in the traditional territories of the Mowachaht and Muchalaht people and established in 1911, was situated where it was, in part, because of its low potential for logging. Nonetheless, upon creation there were still select small-scale logging tenures within the park’s boundaries. When the logging lease-holders tried to cash in, demanding money from the government or exchange for leases elsewhere, the government wrote an Act such that Strathcona Park mining and logging rights holders could retain their rights (but not necessarily exercise them).22

In subsequent years, the Victoria Chamber of Commerce lobbied the provincial government to acquire the logging leases outright, but Liberal Minister of Lands T.D. Pattullo declined, retorting that “We can’t have our cake and eat it as well. We can’t leave timber standing and expect to build up a lumber industry.”23

The Alpine Club of Canada, Vancouver Branch, protested in 1926 that the potential logging would “defeat the whole purpose for which the park was created.” The Club’s argument rings familiar to contemporary ears. “…Any immediate return for the present day speculator is infinitely small compared with the economic value of the timber in its present state as an integral part of the park…” The alpinists continued that the park was a more useful tool for development in its unlogged state, because “advertising, investment and settlement… follow the trail of the tourist.”24

In anticipation of the day that large timber stands would be scarce on the coast, a subsequent Conservative government did purchase some of the timber leases, in 1929, for $335,000 (or, according to the Bank of Canada’s inflation calculator, $5.2 million in 2021 dollars).25 This expenditure banished most logging from inside the park, however, a decade later there was a renewed controversy along the park boundaries.

In 1941, word spread that the British American Timber Company and the Baikie Logging Company intended to log the remaining, unextinguished leases on the eastern shores of Buttle Lake.26 This eastern shore was privately-held land, being inside the Esquimalt & Nanaimo Railway belt.27 The logging operations were protested by William Reid, president of the Hancock Oil company of California, and president of Ducks Unlimited, who owned a summer home at Buttle Lake.28 Reid’s cabin, on the west side of the lake and inside the park, was courtesy of a prior mining claim that he had purchased in 1935.29 Reid was joined in his opposition to the logging by conservationist and photographer Irving Brandt, Vancouver Island author Roderick Haig-Brown, as well as the newly formed BC Natural Resources Conservation League.30 This constellation of wartime influencers was as contemporary as anything promoted today on Vancouver Island, save the lack of Indigenous participants.

By the 1920s through the 1940s, it was not so difficult to imagine a time in the near future in which Vancouver Island forest riches would be in shorter supply.

Ultimately, the provincial government acquired control of five timber limits fronting the lake, representing 340 acres, via a timber exchange. The Strathcona Park controversy can be distinguished from both those today, and those historical cases already described. At issue here was logging in and around a provincial park, rather than the mere felling of “forest.” The park was an area which, by definition in many minds, precluded industrial logging. The park status made it easier to make the anti-logging case.

One element that the Strathcona Park protests shared with the contemporary protests was an additional challenge faced by those with logging rights: a changed public perception of the provincial forest. By the 1920s through the 1940s, it was not so difficult to imagine a time in the near future in which Vancouver Island forest riches would be in shorter supply. In the 1930s and 40s, especially, there were genuine fears of an impending timber famine (and these fears would not be suppressed until postwar sustained yield policies were implemented).31 Within this context of 1943, The British American Timber Co was happy to accept an exchange for rights elsewhere. In the public interest, however, The Elk River Timber Co Ltd. gave up their rights with no compensation, thus establishing a generous precedent that H.R. MacMillan would follow a year later with the donation of Cathedral Grove. Not included in these Strathcona Park agreements was one tract at the extreme north end of Buttle Lake, out of which flowed the Campbell River. This area was already in an advanced state of logging operations.32 There, Reid asked friend (and former American politician) Harvey E. Harris to engage in a dialog with the Minister of Lands and Forests, Wells Gray. Gray visited the site and Harris negotiated an agreement for a 400-foot fringe of trees to be left around the logged over area.33 Further out of sight, but still inside the park, loggers also still worked old tenures in the vicinity of Oshinaw Lake, in the park’s southeast, and in the Elk River Valley, in the north, and this continued untrammeled into the 1950s.34

Please return to the NiCHE blog on January 14, 2022, for part 2. In that post, we will explore another two cases, and present some analysis and concluding thoughts.

Feature Image: “The Gallant Defenders of Deadman’s Island,” 1909. City of Vancouver Archives CVA 480-211.

1. A good entry-point to this literature is Chapter 1 of Richard Rajala’s 1998 Clearcutting the Pacific Rain Forest: Production, Science and Regulation, UBC Press, Vancouver. Richard Somerset Mackie’s books, Island Timber (2000) and Mountain Timber (2009), both from Sono Nis Press, are excellent to illustrate the rail period, while a profusely illustrated account of the truck-era is the commissioned anniversary volume, D. Brownstein and J. Howes. 2018. Timber Forever! Standing Tall & Strong for 75 Years: the Truck Loggers Association, Klahanie Research Ltd, Vancouver.

2. And indeed, this partial blog post continues that “incomplete” tradition, but it is a start. The most encompassing account of twentieth-century forest policy critiques appear in Jeremy Wilson’s 1987 “Forest Conservation in British Columbia, 1933-85: Reflections on a Barren Political Debate” in BC Studies, no 76, pp 3-32; also his 1998 Talk and Log: Wilderness Politics in British Columbia, 1965-96, UBC Press, Vancouver.

3. This story is well-known to students of local history. See pp 63-75 in Sean Kheraj. 2013. Inventing Stanley Park: an environmental history, UBC Press, Vancouver; Daniel Francis also begins his new book with the Deadman’s Island episode. It is Becoming Vancouver: A History, Harbour Publishing, Madiera Park, 2021, p 2.

4. Readers might learn more by consulting Kathryn McKay, 2002. “RECYCLING THE SOUL: Death and the Continuity of Life in Coast Salish Burial Practices,” unpublished MA thesis, Dept of History, Uvic. https://web.uvic.ca/stolo/pdf/McKay_thesis%20-%20pdf.pdf

5. “Reportorial Rounds” The Province, 3 January 1899, p 8.

6. Kheraj, p 64; also see the extensive media coverage.

7. Kheraj, p 70; and again, extensive press reports.

8. “Ludgate was handcuffed… a scene of great excitement” Vancouver Daily World 15 May 1899, p 2.

9. David J. Sandquist. 2000. “The Giant Killers: Forestry, Conservation and Recreation in the Green Timbers Forest, Surrey, British Columbia to 1930,” unpublished MA thesis, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, p 17.

10. Sandquist, p 65.

11. Sandquist, p 76.

12. The railway belt lands would not be returned to provincial control until 1930.

13. “Last of Green Timbers Passes” Vancouver Sun 28 Aug 1930.

14. “Last ‘Green Timbers’ Giant Falls: End of Logging Area Marked by Ceremony” The Vancouver Sun, 29 August 1930, p 20.

15. Logging camps were also required to provide modern laundry, bathing facilities, proper urinals, and implement the “pail system” for defecation. Spitting or blowing noses onto the ground and all other “filthy habits” were absolutely forbidden. Mark Kuhlberg, 2016. “‘An Eden that is practically uninhabited by humans’: Manipulating Wilderness in Managing Vancouver’s Drinking Water, 1880-1930,” in Urban History Review, pp 18-35.

16. Kulberg; “North Shore to get Line” in The Province, November 26, 1924, p 1.

17. David Brownstein. 2016. “Spasmodic research as executive duties permit: Space, practice and the localization of forest management expertise in British Columbia, 1912-1928″ in Journal of Historical Geography, vol 52, pp 36-47; “Pure Water For City Depends On Care Of Forests: Engineers Declare Watershed Should Not Be Denuded of Trees” The Vancouver Sun, 13 May 1923, p 26; “Mayor Says Water Safe: Declares No Necessity to Purchase Timber Lands for Conservation” The Vancouver Sun, 1 June 1923, p 1; “Ratepayers Vote Today On Bylaws” The Vancouver Sun, 16 June 1923, p 14.

18. “Offer Still Stands” The Vancouver Sun, 18 June 1923, p 12.

19. Brownstein, p 45.

20. “Loggers Will Quit Capilano: Water Board Today Ratified Important New Agreement” The Province, 4 October 1933, p 2; “Water Supply For 3,000,000″ The Vancouver Sun, 4 December 1933, p 7; “Watershed Is Public’s Own” The Province, 4 December 1933, p 4.

21. Paula Young. 2011. “Creating a ‘Natural Asset’: British Columbia’s First Park, Strathcona, 1905-1916″ BC Studies, no 170, p 19.

22. John Dwyer. 1996. “Conflict Over Wilderness: Strathcona Provincial Park, British Columbia”, unpublished MA thesis, Dept of Geography, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, p 118; Young, p 33.

23. “Government Cannot Stop Desolation of Strathcona Park by Cutting of Timber” Times Colonist, 20 May, 1926, p 1; also in Wallace Baikie (with Rosmary Phillips). 1986. Strathcona: a history of British Columbia’s first Provincial Park, Ptarmigan Press, Campbell River, p 90.

24. “’Hands Off Park,” Is Cry. Alpine Club of Canada Protests Logging of Strathcona Area.” The Province, 15 June 1926, p 1; “Power Right on Water is Challenged,” Colonist, March 9, 1929, 1.

25. “B.C. pays $335,000 to Conserve Beauty of the Park,” The Province, April 26, 1929, p 8.

26. Yasmeen Qureshi. 1991. “Environmental Issues in British Columbia: An Historical-Geographical Perspective, unpublished MA thesis, Dept of Geography, UBC, p 96.

27. Catherine Marie Gilbert. 2021. A journey back to nature: a history of Strathcona Provincial Park, Heritage House Publishing, Victoria, p 96.

28. “Chief Forester to Investigate: Hart Acts to Save Buttle Lake Timber” Victoria Daily Times, 1 Aug, 1942, p 1; “Land Minister Hurries to Save Scenic Timber,” Times, Aug. 5, 1942, p 1; Arn Keeling and Graeme Wynn. 2011. “‘The Park is a Mess’: Development and Degradation in British Columbia’s First Provincial Park” BC Studies, no 170, p 126.

29. Gilbert, p 88.

30. “Timber cutting at park gateway brings protests”, Times, July 13, 1942, p 1; “Cabinet Action to Save Stately Trees,” Times, Aug. 14, 1942, p 1 .

31. Wilson, 1987, p4.

32. “Tracts Exchanged: Buttle Lake Timber Saved” The Province, 27 May 1943, p 24.

33. Gilbert, p 97.

34. Keeling and Wynn, p 126.

Great pieces of history of forest gluttony in bc. Looking forward to next part!