Editor’s Note: This is the first post in the Northern Borders and Boundaries series. You can read other posts in this series here.

I was astonished when I learned that woodland caribou had once roamed from Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin all the way north to James Bay. I live now on Lake Superior, in a world emptied of living caribou but threaded with their ghosts. We can drink Caribou Coffee, weak as it is, and most suburbs have a Caribou Drive. Each summer for 18 years, I’ve spent most days in a kayak, paddling along Lake Superior islands where caribou once calved. Few of my friends realize that caribou were the most widespread species of the deer family in our northern forests. Even fewer realize that caribou migrations threaded water and island, forest and bog, human and more-than-human together, across what eventually became the Canadian/US border.

Although their annual migrations weren’t as long as those of Arctic caribou, woodland caribou were wanderers, calving on Canadian islands and wintering in bogs to the south. They were survivors. Even as climate regimes dramatically shifted in the Pleistocene, woodland caribou persisted for more than 1.6 million years of dramatic changes. When glaciers encroached, caribou found refugia in what’s now the southern US; when temperatures warmed, they moved northward, with their human kin, along the edges of the melting ice.

But now woodland caribou are struggling. In the US, woodland caribou are functionally extinct. In Canada, of 50 woodland caribou populations, more than half are in steep decline. The litany of losses is all too familiar: Extinct in Wisconsin by 1850 and in mainland Michigan by 1912. The Lake Nipigon population began its steep decline in 1920 when the railway arrived. After World War II, mineral, forest, and energy development in the Canadian north intensified, fragmenting caribou populations. They’ve “been driven off the land,” according to Leo Lepiano, former Lands and Resources Consultation Coordinator for the Michipicoten First Nation.[1]

Consider the Big Bog in what’s now northern Minnesota. This is one of the largest peatland complexes in the world, some 2 million acres of peat that formed when glacial lakes drained. Woodland caribou wintered in these bogs, migrating north across what became the US/Canada border to calve on islands and rocky coasts, where they could find protection from wolves. By the the 1930s, the Big Bog herd were the last woodland caribou persisting in the low 48 states. In 1938, the bog became the site of the first recorded North American effort to translocate woodland caribou. [2]

Boardwalk in the Big Bog. Credit: Nerfer, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Indigenous peoples had thrived in the Big Bog Region for many generations. The Treaty of 1863 forced the Red Lake Nation (Anishinabek) to cede substantial portions of their territory, but they were careful to retain both Red Lake and the Big Bog, where they fished for lake sturgeon, nurtured wild rice and other plants, and co-existed with their caribou kin, hunting them for meat, clothing, and shelter.

In the 1860s, white-owned logging companies began logging around reservation borders. As caribou migrated southward, they were shot in vast numbers to supply meat for logging camps. Whites blamed tribal members for the resultant decline, urging passage of laws that criminalized tribal hunting. When Minnesota’s Nelson Act of 1889 ordered all Anishinabek people within Minnesota to relocate to the White Earth Reservation, so whites could farm their territory, the elders of Red Lake refused to leave either the Big Bog or Red Lake. They did agree to cede 3.2 million acres of their lands outside the bog in return for annual payments. But paternalistic policies ensured that whites, rather than tribal leaders, would determine how those funds could be spent.[3]

In 1908, Minnesota passed the Volstead Act to drain public “swamplands” in the north. Because whites argued that drainage would benefit the Red Lake Nation by forcing them into a settled, agricultural life, they decided to use Red Lake Nation funds to pay for part of the project. Tribal leadership protested bitterly—and fruitlessly—against the use of their money to fund a project that they feared would destroy the bog, Red Lake, and their way of life. Their appeals failed, and the drainage project moved forward, with more than 1500 miles of ditches dug over 6 years.

Photo by Nancy Langston, 2019.

You can predict what happened next. Drained peatlands dried, then burned. Lake sturgeon and wild rice vanished. Caribou drowned in drainage ditches, and survivors retreated deeper into the bog seeking refuge. But as water levels in the bog dropped, wolves could make their way into the calving sites that had once been safe from predation. Farms failed; homesteaders defaulted on payments; and in 1929 Minnesota declared the project a disaster.[4]

Rather than return lands or funds to the Red Lake Nation, Minnesota established the 1,100,000 acre Red Lake Game Preserve. Hoping to restore caribou habitat, staff blocked drainage ditches, re-flooded fields, and dynamited wallows where caribou could find some relief from insects. But soon only 13 caribou remained, and then just 3 (all cows). After building a fence between the Red Lake Reservation and the game reserve in hopes of protecting caribou from tribal poaching, in 1938 staff biologists decided to translocate individuals from a Saskatchewan herd north of Montreal Lake down to Minnesota.

Why this particular Saskatchewan herd? They inhabited a large peatland bog complex, as did the Big Bog herd, so project biologists hoped they would adapt well to the Minnesota habitat. They weren’t long-distance migrants, so biologists calculated they might stay put in their new home.[5] But most important, Saskatchewan was the only province that would give the American biologists a permit to capture and move live woodland caribou.[6]

Dozens of men from the Montreal Lake First Nation, as well as rangers from Prince Albert National Park, joined the expedition. They tried wire snares, traps, a pit, a drift fence, all of which failed. Finally they hit upon soft rope snares, which worked without harming the caribou. Eventually 10 individuals (including a bull and 8 calves) were trucked from Montreal Lake to Prince Albert, then sent by express train over the border to Baudette MN, and then trucked again for the final 35 miles to a corral in the Big Bog, where they “quickly became reconciled to their new surroundings.”[7]

Most of the translocated animals survived only a few years inside the fences. Some were released when they could no longer be fed, and they promptly headed back toward Canada. But development along an increasingly hardened US/Canadian border blocked their migration. Without a way to migrate between calving and wintering grounds, the isolated population dwindled. By 1947, no fresh caribou tracks could be found in the Big Bog.

Seven decades after they vanished, I hiked into the Big Bog along a slippery boardwalk. Ancient depressions in the peat remained, and refuge staff told us those paths had been carved over millennia by the hooves of migrating caribou. A few crumbling fences from the 1930s restoration program were visible as well. But these are ghost stories, fragments of a barely-remembered past. Can we imagine a future that includes living woodland caribou? What would that entail?

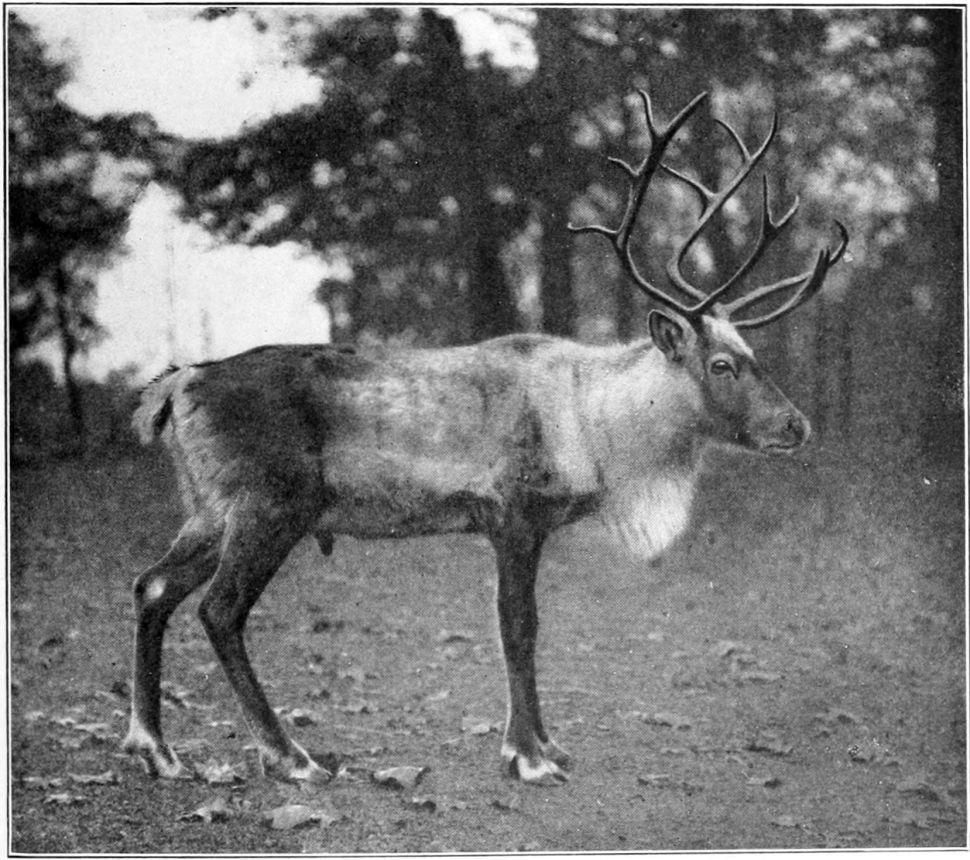

A woodland caribou in 1913. Credit: William Berryman Scott, in A History of Land Mammals in the Western Hemisphere. Public domain.

This is a sad story, I know. But it’s worth re-telling, not only because it’s the first in a long series of caribou translocation attempts. The project’s failure exemplifies the persistent environmental injustice that still undermines restoration efforts. As early as the 1930s, project biologists acknowledged that it wasn’t tribal hunting that was devastating woodland caribou, but rather the destruction of migration corridors.[8] Yet because whites couldn’t imagine that Indigenous hunters could co-exist with caribou kin, rather than restoring these migration routes, biologists decided to fence in caribou, hardening once-porous borders. In my forthcoming Climate Ghosts, I argue that caribou loss was part of a much larger context of Indigenous trauma, and by ignoring that trauma—indeed, by perpetuating the racism that underlay the trauma—project managers doomed the restoration to failure. These are lessons restorationists still need to learn.

Featured image: Woodland caribou on Michipicoten Island in Lake Superior. Credit: Christian Schroeder.

Notes

[1] Langston, “Are woodland caribou doomed by climate change?” Historical Climatology July 2018: https://www.historicalclimatology.com/features/are-woodland-caribou-doomed-by-climate-change

[2] These arguments, and the primary sources that support them, are developed in my forthcoming Climate Ghosts: Migratory Species in the Anthropocene (Brandeis University Press, 2021).

[3] For the Red Lake Nation’s history, see Anton Treuer, Warrior Nation (St Paul MN: MNHSP 2015) and Kathryn Beaulieu, “Mis-qua-Ga-Mi-Wi-Saga-Eh-Ganing History of the Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians of Minnesota.” Red Lake History Project http://www.rlnn.org/MajorSponsors/HistoryProjectBeginning.html

[4] Melissa Meyer and Norman E. Aaseng. “The Red Lake Ojibwe.” In The Patterned Peatlands of Minnesota, edited by Herbert Edgar Wright, 251–87. U of Minnesota Press, 1992.

[5] By 2011, telemetry studies indicated members of this herd remained within a 10 km2 area, but they were captured over a 25,000 km2 area, suggesting the herd was once much more wide-ranging. James Rettie, and François Messier. “Range Use and Movement Rates of Woodland Caribou in Saskatchewan.” Canadian Journal of Zoology 79 (February 15, 2011): 1933–40. https://doi.org/10.1139/z01-156.

[6] Prince Albert National Park, established in 1927, was not far away, and a Hudson’s Bay Company post was also nearby. The HBC, according to a project report written by William Cox in 1939, “generously consented to act as our agent to interest the Indians at Montreal Lake Post in a prolonged caribou hunt to obtain the animals for us.…Meetings with the Indian chief, his counselors, and those trappers who were known to be reliable were immediately held to induce them to take up trapping operations. This was a difficult matter, as the trappers and the Indians were of the opinion that adult caribou could not be taken without injury.” William T. Cox, W. T. “Woodland Caribou in Minnesota.” Soil Conservation 6 (1939): 141-142.

[7] Cox, 143.

[8] In 1936, biologist Gustav Swanson asked why hunting regulations and habitat protection had “utterly failed in the case of the woodland caribou.” The fundamental problem, he argued, was that development had thwarted caribou migrations. Yet Swanson feared tribal poaching, so he urged construction of a 16-22 mile long fence that would completely block caribou migrations. Swanson insisted that “to save the animals from wandering into the Indian reservation where they would be constant danger,” the only solution would be a fence. Swanson, Gustav. “The Minnesota Caribou Herd.” Proceedings of the North American Wildlife Conference Called by President Franklin D. Roosevelt., 1936, 417. In 1938, project manager John Manweiler echoed these themes when he wrote: “The animals used to migrate freely between American and Canadian territory in the vicinity of Lake of the Woods, but with the advent of settlement of the fertile lands bordering that lake and the Rainy River, the Minnesota caribou became separated from the Canadian herds and were virtually trapped in the huge bog area.” Manweiler, 1938, Minnesota Conservationist, “Wildlife Management in Minnesota’s ‘Big Bog,’” 76.

Latest posts by Nancy Langston (see all)

- Woodland caribou and borders - April 1, 2021

- Looking at Canada as a US Environmental Historian - November 19, 2020

- Twinkies, Bug Spray, and Frisbees: Planning For Successful Field Trips - May 9, 2019

- Closing Nuclear Plants Will Increase Climate Risks - January 30, 2019

- The Syllabus Project - July 5, 2018

- Review: An Environmental History of Canada - November 2, 2015