Editor’s note: This is the second in a series of posts considering the intersection between environmental history and gender history. The entire series is available here.

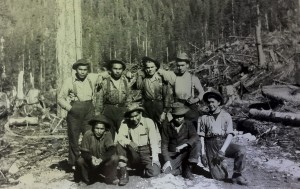

Today, flannel-clad, axe-wielding, bearded fellows are often associated with a bygone era when men proved their self-worth by felling giant trees deep in the forest. The stereotypical logger of the past possessed specific racial and cultural traits: he was male, white, and rugged. This logger is commemorated in nostalgic pieces, such as “The Log Driver’s Waltz,” and in modern popular culture (picture the Vancouver Canucks’ Johnny Canuck mascot). But this image distorts the actual poly-ethnic composition of logging camps. Men from Japan, China, Mexico, South America, and India worked in British Columbia’s logging camps from the late nineteenth century onward. Workers also came from the very places that became logging camps. These latter men are the focus of this post.

Aboriginal people have harvested trees for millennia in the region that we recognize today as British Columbia. Pre-contact woodworkers created practical and often visually stunning commodities from giant cedars, which offered them an avenue for social ascension by providing the items gifted at their own potlatches or those being held by others. [1] With the arrival of Europeans, Aboriginal labour produced timber for many of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s forts. [2] And when Europeans imposed a market economy and wage labour economics upon indigenous space, Aboriginal men became a mainstay in logging camps throughout British Columbia. In these camps, Aboriginal men were treated the same as any other logger; they received equal pay and respect as long as they could work hard and fast. Often, Aboriginal men were often quickly promoted into more prestigious roles, such as ‘rigging slinger’ or ‘hook tender.’ [3] These men also identified as ‘high-ballers,’ an industry term that was only bestowed upon those men that could ‘run like squirrels’ and harvest more logs than most.

Logging camps provided a theatre for Aboriginal men to overcome the racial and cultural oppression that newcomers superimposed upon Aboriginal people in twentieth-century British Columbia. Aboriginal loggers could shed government paternalism and defy stereotypes such as the ‘lazy Indian’ by earning a living and providing for their families and communities. Doing so allowed them to satisfy both Coast Salish and settler notions of masculinity; while each version of masculinity was unique, both highly valued hard work and providing for one’s family. Since many of these men started their careers as loggers at very young ages (often as young as 12), logging became an important means for Aboriginal boys to enter manhood. In logging camps, these boys formed unique masculine identities. They were not just loggers; they were Aboriginal loggers. Many developed reputations as some of the best in the industry.

Although logging camps provided a way for Aboriginal men to affirm their masculine identities, these men were still limited by the racism directed toward Aboriginal people in a settler society. Being a respected logger might have earned Aboriginal men a tip of the hat or a friendly smile from a fellow non-Aboriginal logger in a settler town. But Aboriginal men were still constrained racially by federal and provincial laws that banned them from certain establishments and limited their ability to interact with settler Canadians. [4] Logging sports became a way to bring the skill, talent, and respect these men garnered in logging camps into settler communities.

Logging sports arose in the mid-twentieth century from the competitive nature of logging. Loggers developed reputations in the woods for their ability to perform tasks as quickly as possible. The events in logging competitions are directly related to those performed in the bush: log-rolling, choker setting, cable splicing, belt and spur climbing, bucking, and the springboard chop. Traditionally, the competitors in these games would be the same ones who employed these skills occupationally. At these competitions, in front of crowds that were often predominantly non-Aboriginal, Aboriginal loggers hacked trees, tied cables, and rolled logs along with the best non-Aboriginal loggers.

Several of the Coast Salish loggers that I interviewed for my forthcoming Master’s thesis, “Giant Trees, Iron Men; Coast Salish Loggers and Masculinity,” competed in logger’s sports in the 1960s and 1970s during their time away from the woods. They reflected on such events proudly. Ron John of Chawathil First Nation told tales of besting seven-foot-tall white men in choker setting, boasting, “That really made me proud! He wouldn’t even look at me after.” Similarly, Paris ‘Perry’ Peters travelled all over British Columbia and Alberta, winning trophies for ‘hot saw,’ crosscutting, axe throwing, and spring board chopping. Although the walls in Peters’ Seabird Island home are lined with trophies, he is humble about his success. His wife, Birdie, is less reticent: “He’s not a bragger, I have to do that for him. But he was the best.” [5] For men like John and Peters, competing in logging sports became a way to demonstrate their skills in front of large crowds of people, thus helping to break down the racial and social barriers that existed between Aboriginal people and settlers in the late twentieth century.

Aboriginal men’s success in the commercial logging industry and in logging sports led to the development of “All-Native” logging competitions in the Fraser Valley. At places like Hope and Chilliwack, various Stó:lō nations held logging sports as part of summer festivals. These festivals hosted bannock baking, hop-picking, and war canoe racing alongside logging sports. All of the events, but especially the war canoes and the logging sports, were attended by large crowds of both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people. However, the competitors were solely Aboriginal. One of these festivals, hosted at Coqualeetza (Sardis, BC) in 1977, drew a crowd of five hundred people to watch two days of logging sports. [6] At Coqualeetza, Aboriginal men competed for wooden plaques that were hand carved and painted by Stó:lō artists. [7] Ron John took home several of these, winning events such as axe throwing and cable splicing. John was well-known for his ability to splice cables with only his bare hands, while others had to use tools. He was also named one of the “Top Loggers” on both days of the competition. An “all-native” competition ran in Hope for five consecutive years in the 1970s. Patricia John, Ron John’s wife, remembers that these events “made a strong statement for First Nations loggers, plus we put on a good salmon BBQ!” [8]

As stated by Stó:lō logger Hank Pennier, logging camps provided a space for Aboriginal men where “an Indian can feel as good as the next guy and from what we see in a lot of whites these days, maybe even better than the next guy.” [9] Bringing the talent of these men out of the woods and into settler communities allowed Coast Salish men the opportunity to perform their masculinity in the same way that they had in the woods: by working hard, moving quickly, and often standing toe-to-toe with non-Aboriginal men.

Notes:

[1] For more on the social aspect of Aboriginal woodworking, see Homer G. Barnett, The Coast Salish of British Columbia (Eugene: University of Oregon Press, 1955), 107.

[2] In “After the Fur Trade” (Journal of the Canadian Historical Association Vol. 3, No. 1 (1992), 87-88), John Lutz documents the centrality of Lekwungen labour in procuring the materials to build Fort Victoria. Menzies (“Working in the Woods,” American Indian Quarterly Vol. 25, No. 3 (2001), 412) highlights how Tsimshian woodworkers provided not only the timber, but also much of the labour in the construction of Fort Simpson. The Fort Langley Journals indicate that Stó:lō people provided cedar for the external coverings of Fort Langley in the summer of 1827. See Wayne Suttles and Morag Maclachlan, eds., The Fort Langley Journals 1827-30 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1998), 32-35.

[3] Rigging slingers are responsible for the movement of loggers and timber in the forest. They run a crew of riggers, who attach cables to felled trees and pull them out of the forest. Hook tenders (or hookers) oversee the entire rigging operation. They direct the rigging slinger on which areas to clear, and monitor the flow of logs out of the woods and into the loading or booming area.

[4] Aboriginal people were often required to obtain permission before visiting a neighbouring settler town. Many towns also had laws that required Aboriginal people to leave before sunset. While in settler towns, Aboriginal people were often excluded from establishments that served alcohol. Establishments that did allow them in often had separate Aboriginal seating areas and entrances.

[5] Paris Peters and Birdie Garner, interviewed by Colin Osmond. June 2, 2015, Seabird Island, BC.

[6] “Hundreds attracted to Coqualeetza meet,” The Chilliwack Progress, 31 August 1977, 13.

[7] “Coqualeetza festival final plans in high gear,” The Chilliwack Progress, 17 August 1977, 35.

[8] Ron and Patricia John, interviewed by Keith Carlson, Michelle Brandsma, and Colin Osmond. May 21, 2015, Chawathil, BC.

[9] Henry Pennier, Call Me Hank, eds. Keith Carlson and Kristina Fagan (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006), 58.

1 Comment