PearlAnn Reichwein and Karen Wall, Uplift: Visual Culture at the Banff School of Fine Arts. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2021. 356 pgs. ISBN 9780774864527.

Reviewed by Dale Barbour.

PearlAnn Reichwein and Karen Wall blend the study of art, national parks, education, and Canadian identity in Uplift. It traces the history of the Banff School of Fine Arts from its creation in 1933 by the University of Alberta as a reform movement-inspired extended education program, through its growth in the 1950s and 1960s into a year-round campus program intended to uplift students and fortify Canadian identity in the era of the Massey Commission. Uplift concludes in the 1970s, when the rechristened Banff Centre for Continuing Education was expanded into a world-class centre for special events, management training, and the arts.

Uplift reflects Reichwein’s expertise in social and environmental history and Wall’s expertise in communication, public art, and memory. They build the Banff School for readers and illustrate how attitudes around nature and Canadian identity prevalent in the 1920s were formalized and regionalized in the 1950s. We also get chapters on what involvement with the school was like for students (predominantly women), instructors (predominantly men), and Indigenous people, who are shown to have been more than simply models in an artistic colonial progress narrative. The Banff School offered a wide range of programming, from ceramics to performance, but the focus here is on visual culture.

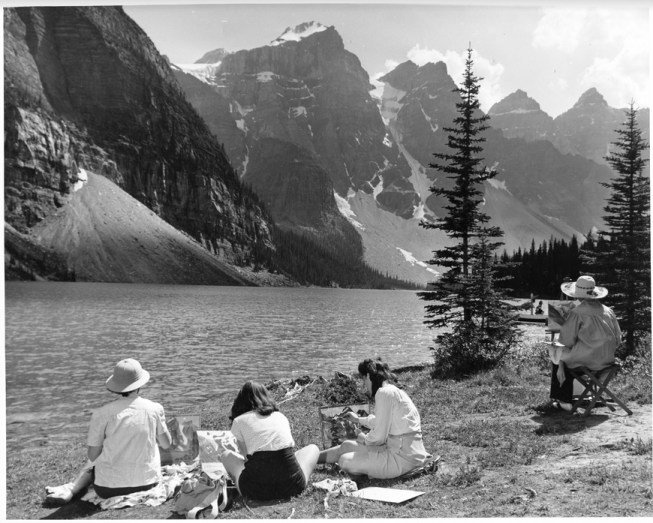

Reichwein and Wall add to environmental history discussions on how nature has been defined as a cultural product by demonstrating how Banff National Park and the Banff School worked in tandem to create a space where people imagined they were immersing themselves in pure nature and emerging fortified, more Canadian, and even uplifted. Students were cultural producers whose artwork trained tourists how to look at the natural environment. Through repeated representation of selected Banff vistas, student artists solidified these spaces as emblematic of the nation. But students were also products: pictures and films of them working in Banff were used to promote both the park and school, and their presence added a cultural cachet to the Banff experience for tourists who spotted them at work.

Countering narratives that Banff was a federal product dropped into the provincial sphere, Uplift demonstrates how the provincial government and University of Alberta used the Banff School to promote the park. School and park bonded seamlessly in the 1930s, when the former used the latter’s townsite infrastructure to hold classes and host students. But as the school moved up the slope of Tunnel Mountain in the 1940s, adding its own infrastructure and residential accommodations, it was quickly seen as competition for the Banff townsite. By the 1960s, dreams of a fully articulated campus were viewed by some as a threat to the natural setting of the park. Canada’s neo-liberal turn since the 1990s soothed these tensions: the school’s need to better monetize its offerings dovetailed neatly with the park’s quest to find new sources of income as government contributions declined.

The Banff School was conservative when it came to art, Reichwein and Wall argue: instructors continued to favour landscape painting into the 1950s when it had fallen out of style in the broader art world. But that conservatism was to be expected: it reflected Banff’s natural setting in driving artistic production and its summer-school setting, which, viewed as an escape by students and instructors, discouraged critical debates about the nature of art. Students were encouraged to get outdoors and do art, rather than fret over what art should be. The conservatism also reflected the tastes of settlers in western Canada, for whom landscape art was both comfortingly familiar and fortifying. The school caught up in the 1960s, with more activist artists and students joining and a regional market increasingly ready for more challenging artistic interventions.

Canadian historians have generally focused on how and why Indigenous people were excluded from national parks or in how their inclusion was strictly mediated. In Banff they were invited in as models to play “Indian” at tourist attractions and as art models for Banff School students. For settlers, these performances presented Indigenous people as a comforting commodity and symbol of Canada along with Niagara Falls or the Rocky Mountains. But Reichwein and Wall show that Indigenous people were more than dupes in a colonial system: they were professional artists, crafters, and actors turning their performances into income and cultural contacts. Chief Tatanga Mani of the Bearspaw Band of the Stoney Nakoda demonstrates the complexity behind pictures of Indigenous models. He played model for crowds coming through the park. He was also plugged into cultural art circles in Alberta, organized Indigenous participation in Banff’s annual Indian Days, and sat at the head table when the University of Calgary, the new home institution for the Banff School, was inaugurated in 1966.

It’s tempting to measure the success of an art school by how many famous artists it produced but Uplift argues that the legacy of the Banff School is better measured by its influence on community leaders and teachers. It was a significant cultural node, drawing artists from eastern Canada, America, and abroad to western Canada (some for a season, some for decades) and giving students from western Canada a gateway into the artistic world. As Reichwein and Wall put it, Banff was a retreat from metropolitan culture for urban students, but an access point for the many rural students who attended. The school produced art shows, exhibitions, and travelling exhibits that brought highbrow culture to western Canada, but its role as an incubator of talent and love for art was even more critical: graduates of the school returned to communities across western Canada to teach, manage galleries, and expand the appreciation of the arts, and thereby a shared way of seeing Canada.

Uplift is illustrated with 30 images, many of them capturing students at work in the epic scenery of Banff. The pictures demonstrate how the camera created scenery, how students produced/promoted certain elements of the park, and how they became products themselves as part of the scenery. But as a visual creature, I would have appreciated a stronger sense of the art being produced at the school, a better sense of where the school was located, and even a map of Banff. Perhaps additional multimedia presentations might be developed, such as an accompanying website that accesses artwork from and even films about the Banff School.

Finally, the book’s conclusion takes us through the twenty-first century as the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity (autonomous since 1978) has struggled with funding, defining its role, and even, in an impressive example of ensuring Uplift is current, the COVID-19 pandemic. Reichwein and Wall end on an upbeat note, speculating on how the school may be able to tap new technologies to build new networks of knowledge. That’s a story we’ll want to hear more about in the future, for although Uplift shows that the Banff School of Fine Arts was deeply plugged into western Canada at a community level, it remains to be seen whether its neo-liberal successor can find a similar level of engagement and influence.

Dale Barbour

Latest posts by Dale Barbour (see all)

- New Book – Undressed Toronto - October 26, 2021

- Review of Reichwein and Wall, Uplift - June 16, 2021

- Muddied Waters and Monkey Trails - July 15, 2020

- Review of Dagenais, City of Water - October 2, 2018

- Liminal Moments on the Way to & from Guimarães - July 28, 2014