Editor’s note: This is the first post in an occasional series entitled “Canopy,” in which leading environmental historians and historical geographers in and of Canada reflect on the field’s past, present, and future, as well as their journeys into and through it. In this interview, series editor Tina Adcock speaks with Alan MacEachern, the founding director of NiCHE and a professor in the Department of History at Western University.

Tell us about how you became interested in studying historical interactions between humans and the non-human world. What key choices, encounters, or moments led you to become an environmental historian of Canada?

Ronald Reagan made me a historian. In the ‘80s, I was convinced somebody was soon going to drop the big one, so in the meantime I might as well do something I liked. Note my assumption that Prince Edward Island was a first-strike Russian target.

But by the ’90s, I was starting to think I’d survive and have to support myself and maybe even a family. So when I arrived at the History department of Queen’s University for graduate school, I asked the 3 questions that every aspiring academic should ask:

- What field do I want to know more about?

- What field is likely to be of only greater significance to people in the future?

- What field doesn’t have as potential supervisors 38-year-olds who will be laying claim to their academic positions for the next three decades?

For the sake of parallelism, I want to say that if Ronald Reagan made me a historian, Colin Duncan made me an environmental historian. And there is some truth to that. Taking a graduate course with him (Duncan) meant being introduced to Glacken, Marsh, Hardin, Lovelock, Leopold, Braudel, Hoskins, etc etc.—and to Colin’s great, quirky mind, and two-sizes-too-big heart. But even before Colin, I was lucky to have as a grad school office-mate James Allum, who was writing what would become a first-rate PhD dissertation on the Trail Smelter Dispute. I learned a lot from him; I feel like I can remember first asking him, “What’s environmental history?” I might take a little credit for my own development, too. I wrote an MA thesis on the history of tourism on PEI. That ended in a chapter on PEI National Park, which led to a bike trip through the Rockies, which led to a PhD on parks history, which led to environmental history. Underlying all this was just a belief that there was lots of work to be done on environmental history, that I couldn’t imagine a future in which environmental issues would be less of a concern, and that in the early ‘90s there weren’t a lot of 38-year-old tenured environmental historians out there.

How has your training as an environmental historian influenced the way your career has unfolded, as a researcher, teacher, and/or community member?

Environmental history feels like one of those subfields, like gender history, whose discovery just opened up whole new worlds to explore. Like you didn’t even know your set of encyclopaedias was missing the G-K volume until you found it. (I should explain: encyclopaedias were sets of informational texts—well, you can look it up on Wikipedia.) I’ll never run out of fun-slash-apocalyptic new projects to work on.

But I’m not sure the “environmental” component of my training has much influenced my career. I’m a soft-core environmental historian. I’ve written about sites I’ve visited, I’ve talked to climatologists, I’ve done a little tree-coring, but mostly I’m like every other historian, wandering through the Internet Archive and wishing that writing was easier. My guess is that this misapprehension about what environmental history is has helped us with colleagues who mistakenly assume that what we do is harder and more science-y than it actually is—but that this has hurt us when attracting undergraduate students into our classes.

The earliest Wayback Machine image of NiCHE’s website from December 20, 2004.

How has the field of Canadian environmental history changed over the course of your career? What have been some of the key developments, in your view?

From the moment that I rode down that golden escalator in New York City, Canadian environmental history has never been the same.

Canadian environmental history has changed, and since I’m in a good position to document NiCHE’s (limited) contribution to that, I’ll focus my answer there.

The Canadian field was on the rise by the early 2000s. About one-third of the Canada Research Chairs awarded to historians to that point went to people doing work at the intersection of history and nature. But there was zero national structure: no formal association, no annual conference, no journal. So when my new colleague Bill Turkel and I saw SSHRC advertising a new “Research Design Clusters” program, we thought that environmental history would be a great fit. And considering the program was being advertised as the first step in SSHRC’s transformation, we thought we’d be crazy not to. We asked six scholars to join us; the three men (Stéphane Castonguay, Colin Coates, Matthew Evenden) did, the three women didn’t. In 2018, we would have kept looking; in 2004, we didn’t. We dreamed up a name—a bilingually acronymable name—for the network, got a lot of buy-in from environmental historians and historical geographers, and we were off. We received $25K in that first year, $25K in the second …and $2000K over the next seven.

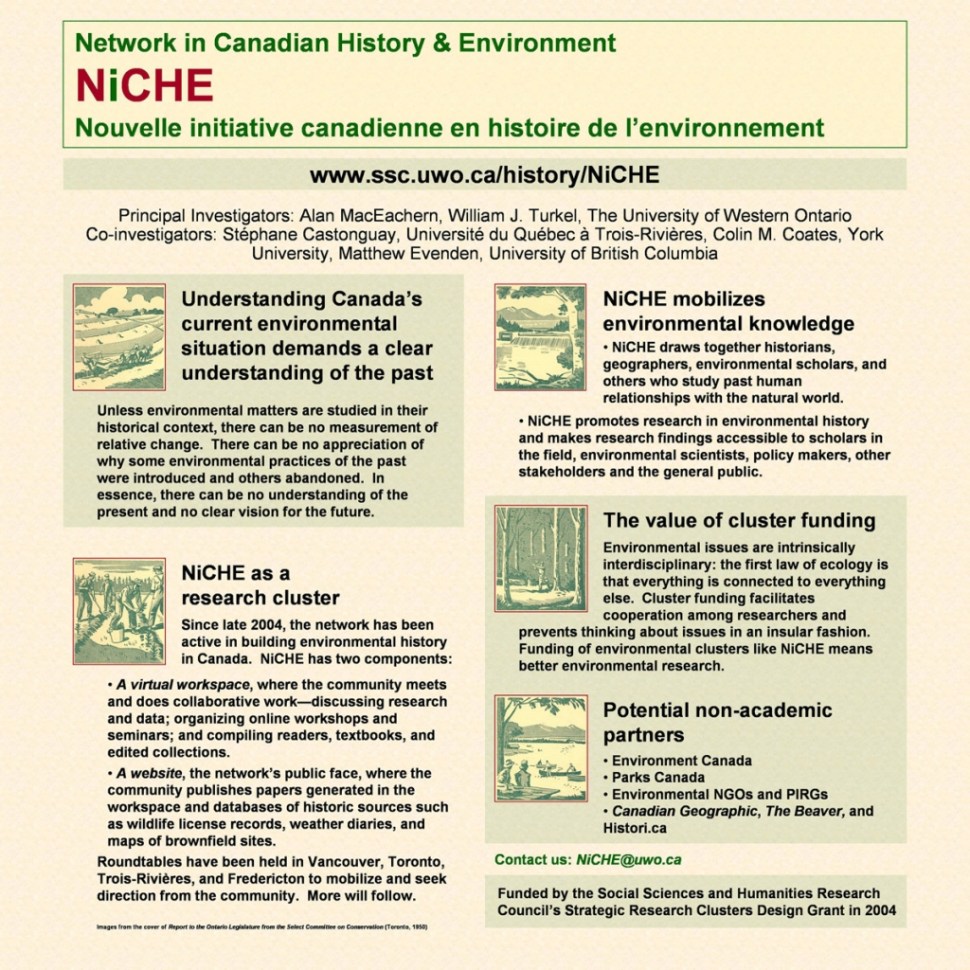

A poster about NiCHE that Alan MacEachern and Bill Turkel put together in February 2005 for a SSHRC “research trade show” in Ottawa.

Maybe it’s telling that I talk about NiCHE’s money before its ideas, but spending the money well and wisely was a big part of that part of my academic career—almost $1000/day for seven years. I remember SSHRC President Chad Gaffield being asked at a talk why these big network grants were only allowed one PI. His reply: “We need to have one person who can go to jail.”

As for ideas, I’m not sure I’ve ever formulated this out loud, but my ideas for NiCHE were more about designing a network than designing Canadian environmental history per se. That was in part because I didn’t feel it my business to define what the field was or wasn’t; I wanted the community to define the field itself organically. And it was in part because of our obligation to SSHRC: the grant was to experiment in the development of a network across Canada’s huge physical space, and the exact topic didn’t matter much.

There are some things we did really well in developing NiCHE. We were relatively early adopters in fostering a digital and digital-literate community. We promoted open-access dissemination of research, like the Canadian History & Environment series at University of Calgary Press. We welcomed and won over graduate students—in part because we figured, correctly, they would become our ambassadors to their supervisors. We developed Canadian History & Environment Summer Schools, and helped hundreds of scholars join the environmental community as well as attend the Congress of the Humanities & Social Sciences on which we were piggybacking. We micro-financed a lot of great projects. And we kept our promises.

But I’d be lying if I said my hopes for NiCHE came close to being fulfilled. I hoped there would be earlier and more openness to open-access publication; for years we tried to encourage—and fund!—the development of research projects on our website, with very little success. I hoped the community would be even more collaborative—using our infrastructural support to join, separate, and rejoin small research groups as needed—and yet also more willing to engage critically with one another’s work. Above all, I hoped members of the community would come to appreciate the prestige—in both the reputational and magical sense—of self-identifying as a part of a unique and uniquely cohesive scholarly network. There has not been much evidence of this. I give a lot of credit to the current Executive for continuing what we did, and doing so with far less funding, but there are few signs of interest across the broader Canadian environmental history / historical geography community in maintaining and building on what we created. And yet we also still have none of the trappings of a typical national field: no formal association, no annual conference, no journal.

What is the greatest challenge that Canadian environmental history faces today? What is the field’s greatest opportunity at this moment in time?

The challenges and opportunities are the same. That there’s been a global cooling to scholarship, while global warming scholarship is more important than ever. That our work can feel so simultaneously meaningful and meaningless.

A poster about NiCHE that Alan MacEachern and Josh MacFadyen created in January 2012.

Reflecting upon your experiences as an environmental historian of Canada, what further thoughts would you like to share about the field’s past, present, or future?

I should have said at the outset: it’s so great that NiCHE is interviewing us oldtimers in the field before we pass on. I’m joking. Or else, like any Maritimer, I’m employing humour as a means of saying something true in a nonthreatening way. I don’t feel deserving of senior-person-in-the-field status, in terms not just of age but of precedence. NiCHE prematurely aged me in so many ways, but one was just by making me seem a more longstanding staple of the field than I really have been. It was folks like Graeme Wynn, Elinor Melville, John Wadland, John Marsh, Chad and Pam Gaffield, Brian Osborne, Ramsay Cook, Bill Waiser, Gerry Killan, and Colin Duncan who spearheaded the study of history and nature in Canada in the 1980s and ‘90s, germinating a community of scholars such as Rick Stuart, Lorne Hammond, Jennifer Read, George Warecki, Neil Forkey, James Allum, Clint Evans, and Ted Binnema—a community I could then join and contribute to.

Pointing forward, as an academic field, Canadian environmental history is at that awkward age where there are a fair number of 38-year-old (or at least 43-year-old) potential supervisors out there, which means there are likely to be fewer jobs in the field in the next couple of decades than there was in the past decade. Oh, and there are fewer jobs anyway. And yet I can’t imagine the world in the next few decades becoming less interested in environmental issues. So we 43-year-olds (cough) have to do all we can to support and sustain the field and its 28-year-old and 18-year-old would-be practitioners. There’s more work to do now than when we started.

Alan MacEachern

Latest posts by Alan MacEachern (see all)

- CHESS 2026: Climate & History – Call for Participants - October 20, 2025

- Events – Artificial | Natural: AI & Environmental History - September 10, 2024

- A Parliament of Cats – Second Reading - August 6, 2024

- A Crash Course in Canadian Environmental History - January 18, 2024

- NiCHE @ 20 - November 20, 2023

- Job – Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Sustainability & the Social, Western University - August 2, 2023

- Online Event – Firebreak: How the Maine-New Brunswick Border Defined the 1825 Miramichi Fire - May 17, 2023

- Storms of a Century: Fiona (2022) & Five (1923) - November 10, 2022

- Climate at the Speed of Weather - October 5, 2021

- Restricted Clientele! Everyday Racism in Canadian National Parks - September 9, 2020

They fixed that thing with Colin’s heart… cholesterol was to blame

Thanks for all the opportunities you have made possible for all Canadian environmental historians and for me personally, Alan! Much much gratitude.