This is the view looking north from an upper floor at the Musée D’Orsay; the Seine is down below. Gallery visitors and tourists see it every day, framed by the outline of a clock. Rivers often serve in cultural history as metaphors of time. Here a clock frames the river flowing past as the minute hand edges along. I saw this view and took this photo while visiting Paris in the fall two years ago. I was giving a talk at the History Department at Sciences Po, hosted by Giacomo Parrinello. While my remarks focused on rivers across borders in the North American experience, I had in the back of my mind an essay on river historiography, and how the way we write about rivers has changed in the past twenty or thirty years.

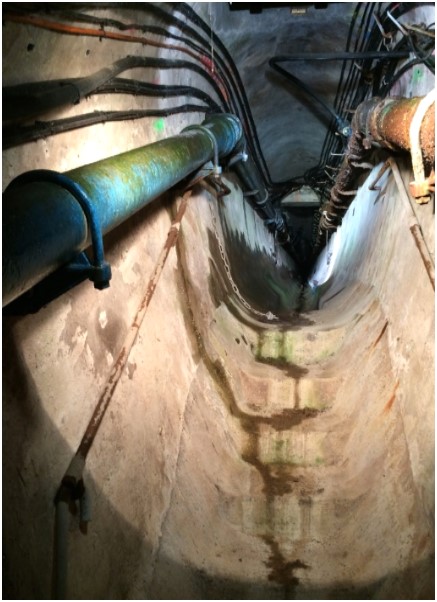

The clock, framing the Seine, arrested me. I could not help but reflect on the profound ways in which this river and this city had co-evolved. The next day, as I descended the steps of the Musée des égouts (Paris’s sewer museum), I wallowed in the muck and foul realities of urban history, intrigued by the pipes and canals that had been constructed under Paris to make urban life possible. Water flowed all around. The Seine surged in and out of the city, like air in the lungs.

Speaking about international rivers in a city founded on an island in a river proved useful to my thinking about river historiography. Notwithstanding the many basin histories which had been written in the previous decades, I was newly struck by the rise of international river histories and urban river histories. These works were different than those that had come before them. Founding works of river history, like Donald Worster’s Rivers of Empire, or Richard White’s The Organic Machine, had many profound lessons to offer but did not concern themselves with the international dimensions of rivers across borders, or the urban scale and the ways in which cities and rivers interact.[1] Worster adopted a political economy focus and analyzed water as a medium of social power; White took a major basin as his focus and sought to transcend nature-culture binaries by asking how energy flowed through human and riverine relationships through time.

We owe a great deal to both perspectives. The river basin has become one of the principal spatial frames of environmental historians and the phrase “organic machine” has taken on a life of its own. Pick up any river history published since the late 1990s and you will likely find it referenced or deployed.

Following my talk in Paris, I picked up a draft paper I had been working on about river historiography and tried to answer the question—how have these foundational books shaped our approaches and how has the field pursued new directions? I read widely. I tried not to prejudge the boundaries of a fluid field like river history. And new books kept appearing. It was a lot of fun. I quickly realized, however, that some limits would need to be placed on the exercise. It would be impossible to encompass all that had been published on river history in the last twenty or thirty years. Some choices had to be made.

My first decision was to emphasize the clear breaks that had developed in the scholarship—writing about international rivers had really changed, and urban river scholarship had grown very quickly just in the past decade and primarily in Europe. I identified Marc Cioc’s The Rhine as a germinal contribution to the field, but also noted the context in which it arose, as water history developed internationally and new research teams formed to tackle rivers across borders.[2] I also considered the extent to which environmental historians had tried to think comparatively about rivers, within and across national boundaries. The relatively new focus on urban rivers suggested the confluence of urban environmental histories of energy, pollution and systems with basin studies, and provided a fertile ground for comparisons. My more fully developed reflections on these two trajectories in river historiography form the basis of a new article in Environmental History.[3]

My first decision was to emphasize the clear breaks that had developed in the scholarship—writing about international rivers had really changed, and urban river scholarship had grown very quickly just in the past decade and primarily in Europe. I identified Marc Cioc’s The Rhine as a germinal contribution to the field, but also noted the context in which it arose, as water history developed internationally and new research teams formed to tackle rivers across borders.[2] I also considered the extent to which environmental historians had tried to think comparatively about rivers, within and across national boundaries. The relatively new focus on urban rivers suggested the confluence of urban environmental histories of energy, pollution and systems with basin studies, and provided a fertile ground for comparisons. My more fully developed reflections on these two trajectories in river historiography form the basis of a new article in Environmental History.[3]

What I didn’t have the opportunity to write about as fully as I would have liked was the enduring tradition of basin histories, which seek to encompass a range of forces and factors in the history of a river, and demonstrate how they come together and reshape social and environmental histories in unpredictable ways. I did mention a few to signal the increasing internationalization of the field, but I didn’t write about how different historians have sought to conceive of rivers in the context of a watershed or basin, and how others have sought to problematize this framing. Where does the river begin, and where does it flow? To whom do basins matter, and why? Environmental historians have reflected deeply on these issues and it is worth considering their different answers.

I ended my reflections on river historiography by suggesting some new directions that river historians might take. First, I think it is high time we develop more explicit comparisons internationally. Every river is unique, but there are historical and environmental processes which provide the basis for fruitful comparison. How have rivers figured in colonialism, for example? Second, I wondered if the emphasis on particular histories of rivers, and the heavy reliance on canonical terms like the organic machine had not hampered more explicit theorizing and methodological innovation. We should try to engage debates more deliberately, for river historians have a lot to contribute to and learn from allied fields. Finally, and relatedly, I called for a more deliberate contribution to studies of the Anthropocene and global climate change. River histories offer the potential for placed-based narratives that can help to animate and ground more globally constructed discourses and scales.

[1] Donald Worster, Rivers of Empire: Water, Aridity and the Growth of the American West (New York: Pantheon Books, 1985); Richard White, The Organic Machine: Remaking the Columbia River (New York: Hill & Wang, 1995).

[2] Marc Cioc, The Rhine: An Eco-Biography, 1815-2000 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002).

[3] Matthew Evenden, “Beyond the Organic Machine? New Approaches in River Historiography,” Environmental History 23(4) (2018): 698-720.

Latest posts by Matthew Evenden (see all)

- Review of Little, At the Wilderness Edge - December 3, 2019

- Rivers re-framed - October 11, 2018

- How the Battle of Britain Changed Canadian Rivers - July 15, 2015

- The Flood Returns - June 26, 2013

- Chlorinating Vancouver’s Pure Water for War - March 19, 2013

- L’Industrialisation des Rivieres / Industrialization of Rivers - September 9, 2009

- A Roundtable on the Past and Future of Hydro in British Columbia - November 10, 2008