Editor’s note: This is the sixth in a series of posts considering the intersection between environmental history and gender history. The entire series is available here.

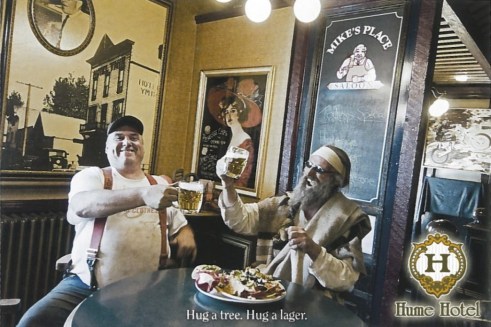

“Hug a Tree, Hug a Lager.” This amusing contemporary ad for Mike’s Place, a popular eatery in the historic Hume Hotel in Nelson, British Columbia, plays on the divisive environmental politics, especially over logging, in the region. [1] It also plays on stereotypical masculinities in this rural community in southeastern British Columbia: the carefree hippie and the hardworking logger.

I find this ad interesting because it echoes Cy G. Russ Youngreen’s “Slocan Man” and “Beer Can Man” comics. Youngreen was part of the back-to-the-land countercultural migration to the Slocan Valley that began in the 1960s. His comics and graphics appeared regularly in The Arrow and other alternative newspapers produced in the 1970s. Slocan Man is a whimsical depiction of the long-haired, bearded men who moved to the region to be closer to nature. [2] Beer Can Man is an unflattering depiction of the “straights” – sometimes pejoratively referred to as the “rednecks” – who opposed the political and cultural initiatives of the “new homesteaders” and did not share the hippies’ appreciation of nature. [3] These caricatures of two opposing cultures of masculinity in the Slocan Valley are a humorous comment on conflicts between neighbours that sometimes became violent in the early 1970s.

The juxtaposition of these divergent masculinities belies the more complicated politics of coalition and conflict in the region’s environmental politics. They also reproduce the false dichotomy between environmentalists and men who work in the woods for a living. [4] Many of the men and women I’ve interviewed for my research on the West Kootenays back-to-the-land movement are deeply committed environmentalists who have also worked in logging-related industries to support themselves. As I will illustrate below, feminist demands for access to well-paying jobs related to logging in this region also challenge our ideas of who worked in the woods. Taking a closer look at the gendered history of work in the Kootenays complicates how we tell the history of environmental politics there.

Many of the men and women who went back to the land aimed to be self-sufficient. Living off the grid proved an elusive goal for most, especially those with children. Newcomers who had professional credentials worked part-time, as substitute teachers or freelance journalists, for example. Others applied for jobs in the mills, and for a while faced discrimination in their efforts to secure such jobs. Mill supervisors claimed that Workmen’s Compensation regulations required men to have hair no longer than the nape of their neck. This allowed them to deny jobs to men who did not conform to their notions of respectable masculinity. [5]

Stereotypes about the counterculture may have also influenced mill supervisors’ reluctance to hire newcomers. Histories of sixties counterculture tend to describe back-to-the-landers as disillusioned middle-class youth who were rejecting the affluence of their parents’ generations. Many were. But I also spoke to men who came from working-class backgrounds, and understood well the need to work to provide for their children. For them, donning plaid shirts and work boots was not merely a performance of rural working-class masculinity. Attention to the class and gender identities of counterculture migrants to the Kootenays challenges the rural working-class man versus urban middle-class environmentalist dichotomy found in many North American histories of environmental politics. [6]

Women wanted jobs in the logging industry, too. A vibrant feminist community developed in the Kootenays, which first challenged sexism within their own progressive community and questioned hierarchical gender relations in their families. Kootenay feminists advocated for women’s equality, paying close attention to the barriers that women in rural, resource-based communities faced. Their debates are recorded in Images, a local feminist newspaper published from 1973-1990. Moving women into “non-traditional work” – or jobs with good salaries that were traditionally held by men – was an appealing policy initiative because there were few alternatives to service jobs for women in the region. Feminists demanded changes to hiring policies that discriminated against women at mills that lacked separate living facilities or washrooms for female workers. In articles written for Images, women who worked in logging urged other women to leave minimum-wage jobs in service. Counterculture women in the Kootenays challenged the male breadwinner ideal, demanding their right to support themselves with well-paying jobs.

Women working in forestry-related jobs also wrote articles that strikingly described the joy of physical work in the woods. [7] Their pride in demonstrating the same physical strength and skill as men in these jobs is similar to the demonstration of agility that Aboriginal men in British Columbia showcased in logging sports, as Colin Osmond explores in his post in this series. Women boasted about their ability to move themselves from the margins to the centre of their job sites as they became respected for their skills. Yet at the same time, they implicitly dismissed the endurance required for women’s paid and unpaid labour in service work and domestic settings. Historians need to better understand how aspiring to masculine jobs in the resource industries and the trades undermined the value of “women’s work.”

Feminists’ demands for meaningful participation shaped the region’s environmental politics in other ways. One of the most interesting environmental campaigns in my research is the Slocan Valley Community Forest Management Project (SVCFMP). This group spearheaded a proposal to develop locally-managed, ecological logging practices in the region. Rather than opposing logging altogether, which these newcomers understood as essential to the local economy, they proposed alternatives to the destructive practices of multinational logging companies. [8] Back-to-the-landers initiated the project and intentionally recruited older men who had worked in the industry to join their numbers. They also united forces with activists who wanted to prevent logging in the Valhalla Range. Ultimately, the collaboration with those committed to creating a provincial park to protect the Valhalla Range did not last, and this group broke away to form the Valhalla Wilderness Society. But for a time, environmentalists and forestry workers together sought a better balance between conservation and logging.

Women held leadership roles both as environmentalists and as workers in the logging industry. Women designed and led community workshops in the Slocan Valley, and the SVCFMP final report was co-written by Bonnie Evans and Dan Armstrong. M. L. Thompson, a member of the Project’s steering committee, had once worked as a secretary in Triangle Pacific. Observing the wasteful and destructive logging practices drew her to the Project. She left Triangle Pacific to join a logging co-op that used horses instead of heavy equipment. She managed the business, but also worked in the woods. [9] Gender historians of work have demonstrated that we must consider gender and class relations as interconnected systems. Considering how gender and class, the politics of work, and neighbourly alliances and conflicts all shaped environmental politics could deepen our understanding of the messy complexities in specific localities, both in the Slocan Valley and elsewhere.

The image of hippies and loggers sharing a pint at a favourite watering hole depicts stereotypes of the community that have become entrenched in the popular culture and self-image of the West Kootenays. But the story in this ad occludes a much more complicated history of the relationship between loggers and environmentalists that played out on the ground in this resource-based economy. From the 1960s onward, Kootenay counterculturalists of all genders worked in the woods to put food on the table. This necessarily informed their environmental politics. Understanding that to be a forestry worker and an environmentalist is not always a contradiction, and that the person wielding the axe is not necessarily a man, adds complexity to the history of Canadian environmental politics in the 1960s and 1970s.

Notes:

[1] “Hume Hotel Ad,” Kootenay Mountain Culture, Summer 2010. For a discussion of environmental politics in the West Kootenays, see Kathleen Rodgers, Welcome to Resisterville: American Dissidents in British Columbia (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014).

[2] Cy G. Russ Youngreen, “Slocan Man,” The Arrow, July 1973. I do not mean to imply that Youngreen was oblivious to women’s contributions. When I interviewed him, it was clear that he supports feminism.

[3] Cy G. Russ Youngreen, “Beer Can Man,” The Arrow, January 1974.

[4] Richard White, “‘Are You an Environmentalist or Do You Work for a Living?’: Work and Nature,” in Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature, ed. William Cronon (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 1996), 171–85.

[5] “To Cut or Not to Cut(?),” The Arrow, June 1973.

[6] Thanks to Petra Dolata for reminding me that class has not received enough attention in environmental histories.

[7] Libby Weiser, “Truckin’ at Tri*Pak or Everyday Brother . . . $35.36,” Images, July 1974; “I Love My Chainsaw,” Images, June 1976.

[8] I examine this project in Nancy Janovicek, “‘Good Ecology Is Good Economics’: The Slocan Valley Community Forest Management Project,” in Canadian Countercultures and the Environment, ed. Colin M. Coates (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2015), 53–76.

[9] Interview with M. L. Thompson and Bill Wells. Interviewed by author, Kaslo, British Columbia, 24 July 2013.

any info (other than Resisterville) on Draft Dodgers ?