Growing up in the 1990s, Oshawa never seemed special or interesting to me, and since I was from “dirty south ‘shwa” sentiments of hometown pride were relatively foreign. Quite simply, Oshawa wasn’t a place that you celebrated, it was a place that people made fun of. I’m not sure when I learned that I was from the “dirty” south end, but I knew it by the time I was ten or eleven. I felt it most acutely as a young adult, when I was confronted with stereotypes over being from the wrong side of town. My identification as a woman made this prejudice even more offensive. As social historians like Mariana Valverde and Karen Dubinsky have shown, being from places considered “dirty” carries a number of derogatory and gendered connotations. Rather than identifying with these stereotypes, like others, I have often found myself questioning their origin. My effort to understand identity formation in the context of industrial spaces has left me with a deep sense of pride for my home—the place that some have cast off as “dirty.” My fascination with Oshawa’s grimy reputation has influenced my research interests, and more recently, my efforts at public history outreach, the result of which highlights the environmental history of a place that was once my backyard: the Oshawa Creek Valley. As part of Doors Open Oshawa happening on Saturday September 26th 2015, I planned and wrote: “History in the Hollows: A Walking Tour of the Oshawa Creek Flats.” Doors Open is supported by heritage initiatives in the City of Oshawa, namely Heritage Oshawa, and is part of a larger Doors Open Ontario series that was created by the Ontario Heritage Trust.

The southern portion of the Oshawa Creek formed the western boundary of the working-class community that I grew up in. As children, the valley was a place of exploration—somewhere we passed through, congregated, and also swam in. More than once, I was scolded by my parents for wading in the creek; we were often reminded that “the water is dirty!” As young people, we were warned of the dangers of the Creek flats, especially when the spring thaw brought the waters perilously high to our local bridge, and storm surges left fallen branches and other hazards. As I grew older, I learned to conceal the time I spent in the creek flats from concerned adults, especially those nights I found myself venturing through the darkness of the valley trails to make curfew on time, or meet friends around a campfire. Undoubtedly, one of the joys of creating this tour has been using my own reflections of life in the creek as the basis for the conceptual hooks that I used to structure the tour content. In this way, I have sought to make my academic research accessible to a diverse population of people who will arrive for the tour with a range of interests and expectations.

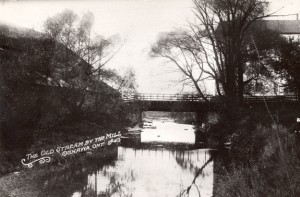

The Oshawa Creek Valley has long been utilized by people—first by indigenous peoples of the St. Lawrence Lowlands, then by European newcomers. In addition to being a source of subsistence, transportation, and recreation for humans, upon the establishment of the area’s first grist mill (see Image 1) and post office in 1838—and the widespread settlement of Europeans on the north shore of Lake Ontario in the last half of the nineteenth century—the nature of the creek, and the surrounding landscape, began to change as industry grew rapidly in the Creek Flats, or “the Hollows.” At the same time that the Creek was being used by a number of different industries, including tanning, canning, and smelting (see Image 2), members of an elite group of Euro-Canadian settlers—namely politicians and industrialists—celebrated the growth and “health” of Oshawa’s industry. Dr. T.E. Kaiser, local physician and Mayor of Oshawa from 1907 to 1908, officially advocated for industry at town council in 1916. In supporting a 1916 by-law amendment to reduce the tariff on McLaughlin motor cars for export, Dr. Kaiser recalled that his work traveling with the Provincial Board of Health “… had taught him [about] the smell and sound of an industrial town. There is a quietness, a dullness and a deadness about the town having no industries, while there are more evidence of life in those that have.”[1] In heralding the town as the “Manchester of Canada” (Image 3 and 4) during this period, local print media documented the prosperity of industry, and supported the notion that healthy towns were those which experienced industrial progress. Other sources I have examined tell a different story, with a 1902 municipal proposal for the town’s first water works outlining that after a half century of industrial activities in the Hollows, water in the Oshawa Creek was already unsafe for human consumption.

My research explores the cultural implications of this environmental legacy by historicizing how industrial space in the southern portion of the city came to be known as dirty and polluted. I argue that this is because the southerly location of industry in the Creek flats weighed heavily on the cultural meanings embedded in the landscape. With this in mind, I have sketched out an industrial settlement pattern that concentrated upper- and middle-class residential and recreational spaces above the geographical line of industry in Oshawa. Quite simply, as far as water was concerned, pollution ran south toward Lake Ontario, through areas that came to be entrenched as industrial, working-class, and “dirty.” My dissertation argues that this is the root of a long-standing myth pertaining to south Oshawa, and the people who live there. As I know, these environmental realities have had deep cultural permanence. These meanings have come to characterize a public discourse that continues to reproduce the stereotype that south Oshawa is dirty and polluted, while in north Oshawa, notions of upper-class cleanliness and respectability continue to give meaning to the landscape and the politics of space. Oshawa’s character has shifted from a city that (historically) polluted the Oshawa Creek in the name of industrial development, to one that cooperates with other governmental agencies like the Central Lake Ontario Conservation Authority to preserve and monitor the Oshawa Creek Valley and other branches of the watershed it belongs to. However, the ghosts of nineteenth-century contamination continue to haunt the valley and the creek (or “crick” as it is still pronounced by some local residents). From a social justice perspective, this is significant. A child of a working-class south Oshawa neighborhood, grit was—both physically and ideologically—are central to my identity. I have come to recognize that this reality is a layered one—wherein the grittiness of an industrial landscape has merged with the politics of identity formation. As I hope to show tour-goers, being from an industrial space is a complex reality and is not something to be ashamed of, despite a popular discourse that sometimes sends this message.

On a related personal note, planning a tour around my dissertation has supported productive research and writing, and also pushed the thematic limits of my dissertation writing. I’ve found that there are many parallels between the academic narrative I am creating in my graduate work, and my bias as a local working-class daughter, although this hasn’t come as much of a shock to me. Despite this, this initiative has helped me to come to terms with the value of my perspective as a person who has played, worked, and lived in Oshawa’s industrial landscape. This became even more apparent after I reconnected with a childhood friend last week. At our chance encounter, I explained my current research to him, to which he excitedly mentioned the old Robson leather tannery (see bottom left corner of Image 2) up the Creek, the remains of which stood as part of the skeleton of nineteenth-century industry near our childhood homes. By exclaiming that “they polluted our creek,” my friend signaled to me that from a social justice perspective, the work I am doing resonates with people. When I began working on this tour last year, I wondered if anyone in Oshawa would care. As I have worked through the planning stages, I have found enthusiasm and support in many unexpected places—including from a local city councilor, municipal staff, and others who are passionate about local heritage. This has helped to inspire me intellectually as I push forward with my research and writing.

Of course, creating this tour has not been without its challenges, but the rewards have far outweighed these. The proposal and creation stages were especially tedious and time-consuming. Although soliciting volunteers to help bring the tour to life was simple—my colleagues and friends provided support and encouragement in many ways—writing the script, seeking formal approval, and finding a way to standardize content delivery have all complicated the process. As far as my dissertation research is concerned, this project has been a useful exercise in articulating some of the broad themes emerging from my dissertation research, which have been deeply influenced by my graduate training in history at York University. Central to these are the concepts of continuity and change, and also the more obvious premise of human agency. Because I have sought to convey these ideas in a platform that is free from jargon, and widely accessible, “History in the Hollows” asks the public to see the river from the vantage point of human efforts to use and control the natural environment. Although the tour content commemorates the role of municipal works in our lives, namely bridges and road building, a less salient goal of mine has been to also highlight the consequences of technological progress in human modes of adaptation. In showing the public what happened when the Hollows struck back against the unbridled efforts of industry to exploit the resources of the Valley, I hope that this initiative will leave people with a more complex understanding of agents of historical change. Although this tour celebrates technological innovation from the perspective of municipal works—something that fit well with a city-run initiative—it also supports critical historical thinking by opening a space for participants to consider the collateral damage wrought by applications of science and technology in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Oshawa. On the other hand, this tour will also ask how humans, and the natural environment, have also expressed resilience and defiance against one another. As Image 4 demonstrates, people sought out ways to adapt to the whims of the creek by creating makeshift bridges, petitioning the town for more bridges, and generating a consensus that council must implement a public works solution to stop the spring flooding in the Hollows, something which was widely documented by area residents, as Image 5 depicts.

If you are interested in learning more—including the role that the Oshawa Valley has played in recreation and sport in the city—please join myself and a group of graduate students from the Department of History at York University on Saturday September 26th. We would be delighted to time travel with you along the creek. The tour is supported by a number of visual aids, including a number of excellent historical photographs from the Thomas Bouckley Collection, which is curated by the Robert McLaughlin Galley in Oshawa. Here is the official tour description:

This tour takes participants on a 45 minute journey along the Oshawa Creek, between King Street and John Street. In giving eyes to the history of the Creek flats, or “the Hollows,” this tour offers visitors the chance to consider the history of Oshawa from the perspective of the river, the environment, and humans. This tour is digitally supported, and tour-goers are encouraged to use their smartphones to access a historical photo-stream created for the tour, in addition to other visual supports offered by guides. Tours are free and leave every 30 minutes from 10 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. from Oshawa City Hall, 50 Bagot St., in downtown Oshawa. Go train service runs regularly from Toronto to Oshawa on Saturdays.

[1] “Oshawa Promises to Become the Automobile Metropolis of the Dominion if By-Law Passes,” The Ontario Reformer 23 June 1916, 1, Oshawa Community Archives.

Amanda Robinson

Latest posts by Amanda Robinson (see all)

- History in “the Hollows”: Environmental History and Local Heritage in Oshawa, Ontario - September 18, 2015

- “A Terrible Fright”: A Short History of Early Aviation in Oshawa, Ontario - May 7, 2015

- Dislocated Landscapes: The Motor Car and Social Inequality in the Cultural Realm - February 5, 2015

- “Landscape, Nature, Memory”: Touring Vancouver by Foot - November 5, 2014

- Recollections from a 905-er: (Re)positioning the Suburbs as a Site of Inquiry - June 17, 2014

This was very well written and totally captures the true nature of our highly influential and indeed prosperous city.

A fascinating article. I would also suggest that the “dirt” in the south end was not only industrial but possibly the by product of cultural and religious prejudices . I grew up in Cedar Dale when there was still a large population of immigrants from the Ukraine, Poland, Slovakia and Russia (let alone a few working poor Scots and English families like my own family). The fact that these people were both Roman Catholic (Eastern and Latin Rite) and Orthodox in a predominantly Protestant and proudly Orange community, didn’t speak the King’s English,and were part of those suspicious dirty “Eastern hordes” immigrating (“invading”) to Canada may have something to do with South Oshawa as being an undesirable and dirty place for upper class British Protestants. Research among Oshawa’s south end Eastern European communities may add another layer to you’re research.

(PS my maternal grandparents (north enders) were aghast when they found out that my mother was dating a Cedar Dale boy-eventually my dad!)

Dear Dean,

I am incredibly heartened by your comment. Thank you and I will most definitely integrate this ethnic analysis into my research. This article focused on a very specific part of my dissertation, but I definitely work in discussion and critique of racial privilege. Much gratitude Dean.

PS

My Dad can remember when the Oshawa Creek ran emerald green or blood red when the Tannery dumped its excess dyes directly into the creek. He also said it was common knowledge amongst the Cedar Dale boys never to swim south of the Tannery. I remember playing in and around the old abandoned Tannery and the presence of office debris, old hides and chemical waste was still present.

Dear Dean,

I would love to talk in person in the future. Please email me at robin25@yorku.ca. You are expressing an incredibly valuable version of the past, and I would love to interview you formally about your experiences. AR

I also remember the creek flowing different colours from the tannery growing up on Wellington St . The big grasslands just north of the creek by lakeview park was a total environmental disaster back in the 60’s 70’s.There was also a certain smell in the air in the summertime that I can still faintly smell even today.

An interesting article about the history of our city. I was born in Oshawa, and have lived year for all but ~5 of my 51 years. I grew up downtown, and have lived in a few different areas, both north and south of King.

I have worked in the GM plants as a summer student, as well as the offices, and now travel regularly throughout the GTA and most other major cities in the rest of the country. In other words I know Oshawa, and I know the perceptions outside Oshawa.

The “Shwa” moniker did not exist when I was young. My father is also born and raised in Oshawa. He is a former City of Oshawa police officer (before the Durham Regional Police was formed), and he does not recall the term ever being used when he was younger. You never heard the phrase inside Oshawa – it began outside Oshawa.

The industrial history is quite interesting and no doubt accurate, but I believe the ‘dirty Shwa’ reputation is a much more recent development for Oshawa and is based more so on socio-political demographics. Within my lifetime there are very well known specific areas associated with poverty and crime. It’s unfortunate, but it’s reality. These areas actually exist in both the south and north ends of the city, but the proximity to the GM plants in the south end perpetuated the ‘south-of-the-tracks’ stereotypes that exist in many major cities in North America, especially in the US. There is also no denying that there is a clear difference in the median household income between residents in the north end versus the south end. The huge variance in property taxes alone will tell you that. However, I don’t think it’s the “south end” that’s the root cause of the reputation cast upon the entire city.

Our society has been heavily indirectly shaped by osmosis due to influences in the US and the associated stereotypes that comes with that. Before the Internet, 90% of the population of Canada was within broadcast range of American radio and TV stations, and that includes all of Oshawa.

At its peak the GM installation in Oshawa represented the 3rd largest operation in the GM corporation. It was huge. I estimate there was a combined total of ~20,000 employees directly employed by GM, both hourly and salary. That’s before you consider the indirect jobs as well. When there was a GM strike, it only took a couple weeks before the Prime Minister got involved because of the domino effect in the overall economy. The whole country, let alone the GTA, used to identify Oshawa with the auto industry.

Combine those perspectives with what happened in Flint, Michigan and the acclaimed documentary by Michael Moore (Roger and Me) and you have the foundation for what quickly became the fear that Oshawa would become the next Flint, Michigan. Fortunately that never happened, but the associations still prevailed. Because of the association with the auto industry, Oshawa has always been considered as a parallel to both Detroit and Flint simultaneously….and now look at what Detroit has become.

I believe the ‘dirty Shwa’ distinction is more associated to this than the industrial history in the early part of part of the last century. I contend the ‘dirty Shwa’ moniker started to emerge around the same time as the demise of Flint, Michigan in the late 80’s.

Just my $.02 for a Thursday

Paul Mason

Dear Paul,

Thank you for the time you took to write this thoughtful post.

Just a clarification that I have never used the word “‘shwa” in my academic writing on this particular topic, and I am fully aware that this term has a more contemporary heritage that the period I am talking about. I am speaking specifically about industrial filth and dirt that was a result of the process of industrialization in Oshawa in the late nineteenth century, almost a hundred years earlier than the period you are giving valuable context to. Thank you for all of the detail and insight you provide on contemporary identity politics, and the economic role that the automobile industry has played in Oshawa. I do not discount the importance of this industry to current identity politics. My work seeks to give context to an earlier period, when Oshawa moved from being the “Manchester of Canada” to “Canada’s Motor City.” There is continuity in the industrial reputation of the city not just from the automobile age, but from an earlier period where Oshawa was not just an auto town, but an industry town, one with a very high percentage of workers in multiple industries–roughly 23% of the town according to the 1870 census. The industrial heritage of the southern portion of the city played a role in identity politics long before General Motors moved south of the city in the 1950s. This is what my research explores. In this way, you can see the continuation of an identification of the southern portion of the city as industrial into the late twentieth century and the present day. Here I hope to give context to the layered nature of these identities, and not something that was just invented in the twentieth century. Certainly I would not discount current economic and political circumstances in the meaning we give to our landscape now, but since I look for continuity and change over-time, I can most definitely see that in historical documentation of industrial lands in the south long before the automobile was affordable to the average person.

While the term ‘shwa was invented in the 1980s, as you and others argue–and which I have never contested–the cultural meanings that assign meaning to this term are part of a larger process of knowledge production that is rooted in a historical context. My training as a historian tells me that these meanings are not generated in one time or place, but over longer periods of time wherein complex, and even contradictory meanings, are embedded in the landscape.

Respectfully,

AR