As summer winds down, academia collectively returns to a more focused routine. Research trips, conferences, and well-deserved time spent with family shifts to classes taught or taken and papers, written or evaluated. Here is hoping all those who read the Otter-La Loutre Blog had an enjoyable summer. I hope your chances to get away have refreshed you and, perhaps, provided you with experiences to augment your current research projects. A recent camping trip to Millinocket, Maine provided me with both a chance to refresh and reflect. This town, sixty plus miles north of Bangor, the last major city in Maine before entering the sparsely populated northern region of the state, experienced significant changes that permanently altered the region when its pulp and paper mills closed over the last twenty years. The choices that the town and state face about the future reflect the region’s environmental history, as evidenced by the ongoing debate about turning part of the region’s forests into a US national park.

Millinocket stands in the shadow of Mount Katahdin, the terminus of the famed Appalachian Trail. The Penobscot band of the Wabanaki people, who lived across northern New England and Atlantic Canada, believed Glooscap, creator of the world, lived in the headwaters of the Penobscot River adjacent to Mount Katahdin. Henry Thoreau visited the region and penned The Maine Woods about his trip. Although not as famous as Walden, his work stands as testament to the region’s natural beauty. In the mid twentieth century, former Maine governor Percival Baxter of Portland donated land to the state that he bought from Great Northern Paper, remarking, “Buildings crumble, monuments decay, and wealth vanishes, but Katahdin in all its glory forever shall remain the mountain of the people of Maine.” This land became Baxter State Park. During the summer months, one can stand outside the Abol Bridge store and watch weary but proud hikers descend the final summit of the six-month trip. I have never had a clearer understanding as to how and why someone could drink a beer and eat a high-calorie sweet in about thirty-seconds. Cheers!

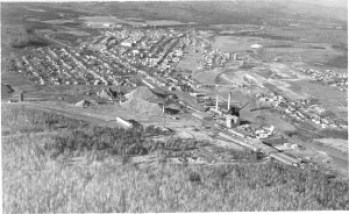

Between Thoreau’s trip and the region’s function as a hub for rafting, hiking, and hunting experiences, the town functioned as the largest pulp and paper processing location in a state covered ninety percent by forest. After the Bangor-Aroostook Railroad was established, the area at the halfway point between Bangor and the small cities and towns of Aroostook County developed to harvest the region’s ample timber supply. Millinocket was born. Great Northern Paper established a company town by building mills, developing a gridded road pattern, and building employee housing. By the 1960s, the mills of Millinocket and East Millinocket, “the town that paper made,” employed more than 4,000 of the region’s nearly 8,000 residents.

While forestry activities disrupted the region as an ecological system – smoke lowered air quality and pollution discharge lowered water quality – a unique culture and dialectic with nature emerged in this wooded and isolated region. In one sense the town was, and still is, fiercely independent. It is part of New England, but more than five hours from Boston. In another sense a gritty culture developed; with shifts operating twenty-fours hours a day, one of the local bars might be carrying on at full-bore as other residents rubbed their eyes and readied themselves for another work day. High school sporting matches brought out most of the town’s residents; state championships that adorn the school gymnasiums stand as a reflection of the community’s intensity and pride. The men and women that operated mills voraciously consuming timber and processing it into paper developed intimate connections with the region, enjoying numerous outdoor activities. When the mills shuttered because of new technology and international competition, the dialectic between nature and culture dramatically changed.

The Northeast and Atlantic Canada Environmental History Forum I attended and presented at recently stimulated me to think about Millinocket in a larger context. (Claire Campbell, an Otter editor and contributor, did an outstanding job organizing this conference. http://nacehf.org/index.html) Attendees at this conference examined Richard Judd’s latest work, Second Nature: An Environmental History of New England. Judd’s introduction describes New England’s contribution to the discussion regarding the nexus of nature and culture. New England, he argues, is a region that illustrates the balance between cultural imperialism and environmental determinism. This is a philosophical debate that underlies environmental historians’ work: do humans act on nature and shape it to their needs or does nature have agency, shaping the culture that springs forth from its woods, streams, forests, and oceans?

We see both processes, environmental determinism and cultural imperialism, at work in New England, but it has led to divergent results for its northern and southern halves. Colonial settlers invaded native peoples’ land, harvested timber, and cleared the region for farming. Yet in the present day, New England is among the most heavily forested regions in the nation, the water quality of its rivers and harbors have been improved, and it has the highest air quality in the US. For southern New England, this has been a boon; much of the region’s four trillion dollar GDP is produced in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. As Millinocket transitions to a post-industrial economy it is still a resource-providing region, but these changes have contributed to larger gaps in economic equality compared to points south than existed in previous generations. The region is starved for economic opportunity, but the question is how tourism positions Millinocket and places like it in an economic and social sense within the wider context of the region.

The discussion regarding whether areas adjacent to Baxter State Park should be devoted to a national park offer competing visions. One area sees economic development within the context of New England’s second nature and the other sees intrusion and dispossession. Many of those in the northern part of the state oppose a national park because it will more strongly establish federal control, potentially threatening hunting and snowmobiling activities. Conversely many in southern Maine favor a national park, led by Portland’s Roxanne Quimby and her son Lucas St. Claire. Quimby, on the list of the largest one-hundred landowners in the US, has offered to donate this land for a national park. After initially acquiring the land, she posted it with “no trespassing” signs, frustrating and angering local residents. Paper companies had traditionally offered its land for recreational use. While this functioned as a salve for economic and environmental exploitation, it also contributed to residents’ connections with their surroundings. St. Claire, who has largely taken over the campaign for his mother, maintains that a national park will bolster Millinocket’s economy and preserve nature. Recent plans show that part of the proposed park will maintain snowmobiling and hunting activities. A national park provides tourism, but service industry jobs often do not meet full-time requirements.

The decision regarding a national park in this region reflects the second nature, and I would add, second culture, that has developed in Maine and New England. Different parts of Maine and New England exert agency on the land around Millinocket. On one hand, those closer to the nature in question prefer their own vision, featuring more control and a continued measure of what they would term independence. On the other, those further away see preservation of nature and a stronger economy in a section of the state lagging behind its southern counterparts. Maine’s great forests have affected residents’ imagination and ethos in different ways. The cultural discussion that proceeds from this point will be shaped by competing visions of economic growth and environmental stewardship. Certainly preservation is desirable, but so is the local culture’s desire to shape the land, water, and air they know so intimately. As we ponder the implications of second nature, we must consider the continued evolution of the culture that interacts with and is changed by the land and water around it.

Mike Brennan

Latest posts by Mike Brennan (see all)

- A New National Park in Maine? New England’s Second Nature and Second Culture - September 2, 2015

- Radkau, Reflections, and the Purpose of Environmental History - May 20, 2015

- A Personal Journey to Understanding Space, Race, and Environmental Justice in Boston - February 23, 2015

- Lewiston, Maine’s Little Canada: Revealing the Cultural Intentions of French-Canadian Migrants - November 26, 2014

- Post-CHESS 2014 Reflections: A Great Time and A Complex Theme - June 19, 2014