5. The Nature of the Work

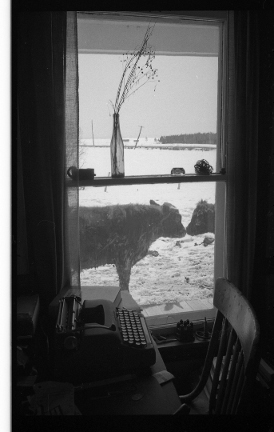

What won over many rural Islanders was that, like themselves, the back-to-the-landers were committed to hard work. Work, says John Rousseau, was what made the movement a religion: "you had to believe in this, that it was a good thing to do." Rick Gibbs, the New York Jew turned pig farmer, found that "[T]he old farmers, what they respected was a good day’s work, a hard day’s work. If you worked hard, they thought the way you looked might have been crazy, but they didn't mind .... The first few years we were farming we did all kinds of crazy things, you know, that didn't work out and the old timers would tell us how to do it better...." Having conceived of their new life as a grand adventure, Rick and Carla found the reality more prosaic. Their first winter, 1975, the water stopped working. "By then we had a cow and goats and horses in the barn. We'd have to go to that old empty house across the road, there was a hand pump behind it, ... and we had to cross the road with buckets. I still remember it took 55 pumps to fill a bucket of water. Haul it back across and then the cow would just — slurrrp — she'd drink the whole bucket. It was tough." And yet Rick and Carla speak of that time not so much with nostalgia as gratitude, that it taught them about themselves. In their interview, they keep coming back to the work. Rick says,

If you cleared the field, you know, and really worked hard on it ... you would have a cleared field that you could feel proud about. Or build a barn, or a herd of cattle that you started with one three-teated cow and ended up with ten real milk cows. You could see something and it felt honest .... The key word for me was that it was honest work. I felt honest about it. I totally didn't know what I was getting into, for sure, but I felt good about those years anyway.

Given the life the back-to-the-landers were attempting, they could hardly help but be bound to their work. Almost from the moment he and his family arrived, Gerald Sutton was not only building their own house with wood hauled from their own forest, and growing their own food, he was teaching high school. He believes that while there were a lot of hippies who were really just slumming graduate students, "the people that stayed were those of us that bought land and didn’t mind doing the work. ...Most of the hippies I know weren’t real workers. You know, to go back-to-the-land you have to do the work."

It was an unusual mix of work. Some of it was just the regular work of setting up a farm in 20th (or 19th) century Prince Edward Island; Christine Stanley building the barn with her baby in a backpack, and her two-year-old handing her lumber, is perhaps an extreme instance of that. Some of it was deliberately premodern while some of it was forward-looking and untried; Morley Pinsent, who lived in South Granville without power, did all his farmwork with draft horses, and taught himself how to butcher, serves as an example of one end of the spectrum, and Roy Johnstone supplying power with a windmill — and so, in wintertime, climbing the 55-foot tower to chip ice off the blades — as an example of the other. We tend to think of back-to-the-landers as anti-technology, but that is a real mistake. Some were intent in developing new technologies, many adopted the lifestyle because it promised closer engagement with traditional existing technologies, and for all it demanded knowledge and a clear focus on how the technologies on which they depended worked.

There’s a thread of great satisfaction, even joy, running through the back-to-the-landers’ interviews, when they talk about what work they found themselves able to accomplish. Having given up a secure way of life in Vermont, David Sobers was living in a tent and, without any experience, began building his own house. When their well was dug,

We thought, 'Wow, that's all you need! We have water — that's just fantastic!' So we lived for a few years without electricity. ... Without electricity, without a phone. We couldn't even afford an outhouse.... I think if we had gone from living in our comfortable suburban existence to an old farmhouse, we might have felt as though it was a come-down. But going from there to a tent, everything we got after that we were so grateful for. To have some walls to shelter us from the wind. We pitched our tent inside. [laughs] Everything we had then we were grateful for, we appreciated, and it was progress for us.

Some weekends, there would be 30 or 40 people from the community watching the house slowly going up. "We built our house and poured the cement.... We did all the framing and everything by hand. We built the roof trusses. I loved putting on the roof. That was kind of neat. It was so satisfying to shingle a roof. You really had a feeling of accomplishment."