This is the seventh post in a series called “From the Outside In,” about the experiences of teaching and researching Canadian environmental history by scholars from other countries.

In conversations with Canadians I’ve sometimes detected what to a Dane with a passion for Canadian society and culture is a perplexing diffidence regarding the youthfulness, even the unsophisticated quality of heritage imprint of settler society on the Canadian environment. The suggestion is that European cultural heritage (of the “Old World”) is richer in authenticity; older and therefore more venerable, somehow. Conversely, many Europeans are likely to be awestruck about the authentic “wildness” of the Canadian natural environment compared to the often very “cultured” environments in which our heritage sites are located. But a closer exploration of two sites in Canada and Denmark suggests that the relationship between environment and public heritage is more complex and more subtle.

In previous work on heritage tourism I have distinguished between indexical, iconic and symbolic authenticity. Basically, indexical authenticity is experienced by a visitor who believes an object to have a factual, spatio-temporal link to the site and its history (a 13th-century sword pommel excavated at the site of the Battle of Stirling Bridge, e.g., would produce this experience to most visitors). Iconic authenticity will be experienced by a visitor who believes an object has resemblance qualities due to it being largely similar to the “real thing” (a 21st-century reproduction of such a pommel, e.g., would likely create this experience). Symbolic authenticity may be experienced by a visitor who is able to appreciate the socio-cultural importance of an object, regardless of it having few or no recognisable indexical or iconic qualities in relation to the event or narrative it communicates (the National Wallace Monument, e.g., erected in the 1860s on a nearby hilltop with its view to Stirling Bridge would have this effect on many Scottish visitors) (Thomsen and Vester 2016).

Authenticity sleuthing is interesting, but has also caused a permanent work injury, which causes me to analyse all the sites I visit, and their possible interpretations, within such a framework. This autumn I was visiting one of the best-known heritage sites in Denmark (in fact a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2000): Kronborg Castle. Surrounded by fortifications in the form of impressive ramparts and ravelins, the medieval/renaissance castle sits on the coast, half-an-hour’s drive north of Copenhagen, in Elsinore. Between the 1420s and 1857 the sound toll was collected here from passing ships under the threat of cannon fire, and for even longer the call “Kronborg on the starboard!” has meant the safe return from a long voyage at sea.

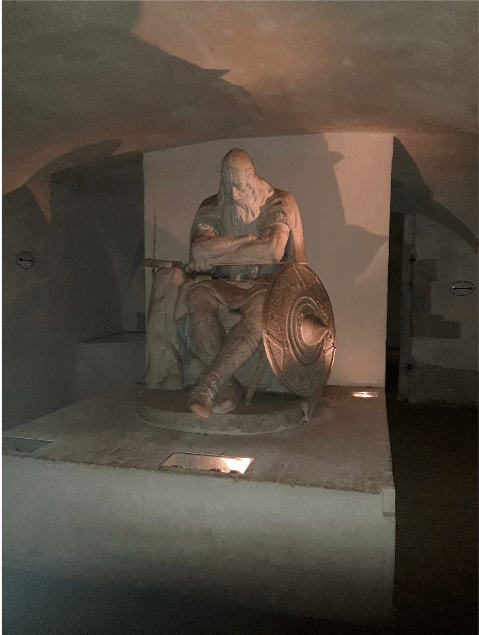

The castle casemates are home to the statue of the legendary Viking hero Ogier the Dane (Holger Danske) − who, according to legend and H. C. Andersen, will awaken to defend Denmark should the country ever find itself in dire need (Andersen 1830). Since Shakespeare wrote Kronborg Castle into one of his best-known plays, it has also been world famous for, allegedly, having once been the home of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark.

I got the distinct impression that the connection of the castle to such mythological characters produces an expectation – probably one accentuated by tourist-commercial interests – that the site provide the opportunity for visitors to encounter the two coryphaei, Ogier the Dane and Hamlet. One senses the tour guides heaving a deep sigh when visitors inquire about Ogier and Hamlet’s whereabouts, assuming their actual, historical relation to the castle. The guides are obviously aware that on the slightest inspection it becomes clear that the connection of Ogier to Kronborg is a modern invention, and the national treasure, the large statue of Ogier that sits in the dramatic catacombs of the castle, is not quite as ancient as it would appear. In fact, it is a 1985 concrete replica that replaced the moisture-damaged 1907 plaster model for a bronze statue, commissioned by a local hotel for its entrance area (SN.dk, 2013). Similarly, the connection between mythical Amled (possibly an early Medieval Jutish king) and Kronborg is entirely the 17th-century fiction of Shakespeare’s well-developed imagination.

Most visitors to Kronborg are thus likely to experience indexical authenticity with regard to the castle itself, its bastions, cannon, and the original tapestries in the great hall. Reproductions and illustrations regarding certain periods are well-considered, and very likely to be experienced as iconically authentic. However, the attempt to cover a diverse spectrum of periods, narratives, and (literary) mythologies to cater to all kinds of visitors’ tastes has obvious disadvantages. In their insisting fame, Ogier and Hamlet may invoke experiences of symbolical authenticity for some, but to any visitor with basic historical knowledge their heavy presence is likely to over-shadow other kinds of authenticity.

If weak on several counts with regard to the authenticity of the toured objects, the site is very strong on others, and setting in particular. The surrounding environment has been carefully restored from post-industrial warehousing to ensure a stunning view of the castle itself, its fortifications and to Sweden across the sound. The Maritime Museum of Denmark – a major three-storey building from 2013 – was built below the ground, in the old dry dock of the local wharf, to allow a free view to and from the castle grounds. The remainder of the old industrial wharf has been transformed into a pleasant stroll-able harbour front, with direct access to the castle via its ravelins (turned lawns). Even if little indexical or iconic authentic experience is the likely outcome of a visit to these outdoors parts of Elsinore, the close connection between the maritime environment and the castle site strongly evokes the symbolic authenticity of a place that remains the prime symbol of Danish naval and sailing history.

My visit to Kronborg reminded me of the Halifax Citadel. The town of Halifax, Nova Scotia, was founded in 1749 as a military counterweight to the mighty French fortress of Louisbourg, and the fourth Citadel, a star-shaped massive masonry construction, was completed in 1856, to guard against attacks from the United States.

In 1980, when Parks Canada decided to carry out a living history program at the Citadel, it chose to fix heritage interpretation in the time period 1869-71. In contrast to Kronborg this means there is a very specific historical focus here. That focus is supported by re-enactments by the Halifax Citadel Regimental Association (HCRA; 78th Highland Regiment and 3rd Brigade Royal Artillery) of military drills and exercises, bagpipe-playing, original Snider-Enfield rifle and cannon firing demonstrations, working blacksmiths and barrel makers etc. (Parks Canada 2020). In recent years the World War I and II exhibits have been expanded, but especially thanks to costumed re-enactments and period furnishing, the dominant impression one gets as a visitor is still one of being transported back to mid-Victorian, imperial Halifax.

Most visitors are likely to experience indexical authenticity via features like the mid-19th-century masonry walls and earthen ramparts. Meticulously recreated uniforms and period outfits are likely to be perceived as iconically authentic reproductions, as is the produce of the working blacksmith, for example. The citadel experience is rich not only in iconic and indexical authenticity, but also, for many visitors, in symbolic authenticity. This is due partly to the interpretive focus on a period with a particular place in the mythology of English (British) Canada, with one of the oldest permanent settlements in what would become Canada, and the place to which many British Loyalists fled after the American Revolution. The Highland regiment focus and the Scottish heritage and military history it commemorates has obvious tartan appeal in this province in particular. The choice to select one particular period of the history of the Citadel is communicated clearly to visitors, and followed through in representations and re-enactments. Consequently, interpretation at the citadel can address specific expectations and thus produce an experience rich in authenticity of most kinds – though not all.

In sharp contrast to the town-planning and architectural decisions that have recreated in Elsinore an open environment which connects the present (refurbished wharf) and the past (Kronborg with its bastions), the carefully designed Halifax Citadel experience falls flat when one’s attention is distracted by the viewscape from the site. Because of the urban density of high-rising buildings in downtown Halifax, even from Citadel Hill it is almost impossible to make the visual connection (and therefore the intellectual association) between the harbour and the citadel, which was originally placed there to defend it. Concerns about protecting the integrity of viewplanes – which allow the site to function interpretatively – have been raised since the 1970s, but anxieties about urban renewal generally lent municipal support to larger infill projects; most recently, the Nova Centre. Such an environment does little to evoke any kind of experience of historical authenticity; indexical, iconic or symbolic.

To me the two sites are representative of the dilemmas that heritage site managers and interpreters constantly face: they seek to create the authentic feeling of having experienced something genuine and truly essential to a community’s social and cultural identity but are often incapable of controlling or even influencing the environment in which they work. Due to progressive town-planning, H C. Andersen, and Shakespeare, in Elsinore the physical surroundings now provide for an excellent setting, while the possibility to focus heritage interpretation is limited by commercial interests and fiction-based expectations. Conversely, in Halifax the heritage site has clearly been given the authority to focus interpretation, and thus visitors’ experience of on-site authenticity, but it is left to do this in a cityscape that can only detract from that experience. One can’t help wondering what it would mean for a coastal city to remember and respect both its topography and its history.

Feature Photograph: Halifax Citadel, courtesy Parks Canada @ParksCanada_NS (2020).

References:

Andersen, H.C. (1830). ‘Et Sagn: Holger Danske’. [https://www.hcandersen-homepage.dk/?page_id=7818].

Parks Canada (2020). ’Halifax Citadel National Historic Site’. [https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/lhn-nhs/ns/halifax].

SN.dk (Sjællandske Nyheder; 2013). ‘Den rigtige Holger er bag lås og slå’ [https://sn.dk/Helsingoer/Den-rigtige-Holger-er-bag-laas-og-slaa/artikel/267902].

Thomsen, R.C. and Vester, S.P. (2016). ‘Towards a Semiotics-Based Typology of Authenticities in Heritage Tourism: Authenticities at Nottingham Castle, UK and Nuuk Colonial Harbour, Greenland’, Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16:3, 254-273.