By Mo Engel, Shannon Stunden Bower, Andrew Tappenden, and William Van Arragon

If you were to ask many Edmontonians today what they think makes their city special, odds are good that, after naming hockey player Connor McDavid or mentioning a particularly sizable shopping mall, a reliable answer would be the city’s river valley. Situated on the banks of the North Saskatchewan River, Edmonton possesses North America’s largest system of contiguous urban parks. Celebrated by many of the city’s residents as a beautiful and placid “ribbon of green,” the parks system winds its way through the city and offers an urban oasis that seemingly brings the wilderness into the heart of the city. As one Edmontonian put it, “Our river is often remote from the hustle and bustle of the city through which it flows.”[1]

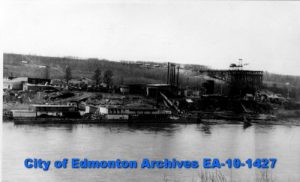

Our project, “Between the City and the River,”[2] is premised on the opposite view—that for all its serenity and beauty the river valley has never been remote from the city and that the historical processes that created it are understood poorly. The dominant civic narrative of Edmonton’s boosters, past and present, describes the historic transformation of the river valley from industrial commercial use to contiguous public green space in highly congratulatory terms, using keywords like “renewal,” “redevelopment,” and “revitalization.” But Edmonton’s river valley parks have been contested landscapes of exclusion and privilege since at least the fur trade era. Edmonton’s hagiographic civic mythologies and memories have methodically erased the river narratives of the area’s Indigenous inhabitants—Cree (especially the Papaschase), Saulteaux, Blackfoot, Nakota Sioux, and Métis. Beyond this foundational history of settler colonialism, the parks were also created by other continuing processes of expropriation and dislocation that have been brought to bear on the city’s urban poor and homeless or transient populations.[3] This history of dispossession and expropriation is one that many Edmontonians are unaware of when they walk, hike, cycle, picnic, and play in the “peaceful” river valley. The answers to the question posed in our blog title (whose ‘Ribbon of Green’?) are more complicated, perplexing, and unsettling than most Edmontonians know.

The primary goal of our project is to build understanding of the complex and conflictual histories of Edmonton’s river valley. We are working toward that goal in several ways. One major effort is directed toward the production of a digital atlas highlighting the lesser-known histories of Edmonton’s river valley. Conceived as a work of public history and animated in part through the use of Geographic Information Systems [GIS], the atlas is aimed at a general audience. Over the past few years, project participants have been working to develop a purpose-built platform to display compelling historical evidence (photos, documents, film, maps, etc) within spatially-oriented narratives. The effort has involved computer scientists and digital humanists collaborating with historians to produce software intended to provide a more satisfactory means of framing arguments about the significance of particular spatial and historical processes. Once sufficiently functional, the software will be released in an open source format. In this way, it will position non-experts to deploy advanced GIS tools in the service of community-based research and dissemination.

Scholars associated with our project will utilize this purpose-built platform to produce atlas content based on original research in documentary records of various sorts as well as on oral histories. Some examples of themes under investigation by involved scholars include debates over freeway construction in the 1960s and 1970s, the management of solid waste in an urban context, the relationship between the valley’s industrial foundations and its “unspoiled” and “natural” patina, and mid-20th disputes over the character of residential communities along the riverbanks.[4]

The atlas will also involve content produced partially or entirely by individuals or groups interested in recording their histories or experiences of the river valley. In this way, our project is oriented to both public history and participatory research. The aim is to solicit material from groups poorly represented in existing historical records pertaining to the river valley, to offer a dynamic platform appropriate to mapping the diverse narratives of the urban river valley, and to generate alternative readings and mappings of the river landscape, especially from groups or constituencies whose voices and perspectives have been marginalized or obscured. The atlas will become an archive of contemporary river valley experiences, one that may serve to provoke new questions for historical researchers. We concur with Jennifer Bonnell and Marcel Fortin that by “enabling researchers to undertake a geospatial interpretation of historical questions, HGIS [Historical Geographic Information System] becomes a powerful method for historical investigation.”[5]

In the development of a GIS-driven historical atlas, we are involved in a project that is fundamentally interdisciplinary and collaborative. The conventional sources of the historian, the presentist biases of the mapmaker, the functional goals of the computer scientist and the narrative orientations of the humanities and social sciences cast each other into relief as they come together in a digital platform oriented to generating a deep history of place that would be difficult if not impossible to otherwise achieve.[6] Communicating our findings digitally allows us to avail ourselves of the affordances of writing, images, maps, annotations, and interactivity in order to tell the story of the river valley in new and varied ways.

Cree and Blackfoot scholar Dwayne Donald, employed at the University of Alberta and a collaborator on our project, has expressed the multiple historical perspectives at play in what is now the city of Edmonton through the concept of pentimento, an artistic effect whereby earlier layers of paint show through later applications. HGIS’s strength is the layering of information, in its capacity to place objects in temporal and spatial relationships. Our atlas will allow a layering of historical narratives, one that evokes the concept of pentimento by peeling away stories obscured by official or colonial histories. “This kind of re-reading of history” Donald writes, “is predicated on the desire to recover the stories and memories that have been ‘painted over.’”[7] By allowing audiences to sift through historical layers, connections between seemingly distinct processes and places will emerge, highlighting the complexities and complications of Edmonton’s river valley and ravines system.

Notes

[1] Quoted in Billie L. Milholland, “The Story of This River is the Story of the West”: Canadian Heritage Rivers System Background Study, North Saskatchewan River, Alberta (North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance, 2005), 10.

[2] See our landing page for more information and future updates as the project proceeds: http://rivervalleyatlas.kcvs.ca

[3] The story of expropriation and dislocation in Edmonton’s river valley is not well explored, though Zoe Todd has offered some important initial interpretations. See Zoe Todd, “Conversations with my Father’s paintings: writing my relations back into the academy,” Activehistory.ca Published 11 January 2016. http://activehistory.ca/2016/01/conversations-with-my-fathers-paintings-writing-my-relations-back-into-the-academy/; Zoe Todd, “Creating citizen spaces through Indigenous soundscapes,” Spacing Magazine, Published 1 October 2014. http://spacing.ca/national/2014/10/01/creating-citizen-spaces-indigenous-soundscapes/; Zoe Todd, “Indigenizing the Anthropocene,” in Art in the Anthropocene: Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environment and Epistemology, eds. Heather Davis and Etienne Turpin (Open Humanities Press, 2015), 241-254. For corollaries in other Canadian cities see for example: Tina Loo, “Africville and the Dynamics of State Power in Canada,” Acadiensis 39, 2 (Summer/Autumn 2010): 23-47; Karen Bridget Murray, “Making Space in Vancouver’s East End: From Leonard Marsh to the Vancouver Agreement,” BC Studies 169 (Spring 2011), 7-49; David G. Burley, “Rooster Town: Winnipeg’s Lost Métis Suburb, 1900-1960,” Urban History Review 42, 1 (Autumn 2013), 3-25; John Meligrana and Andrejs Skaburskis, “Extent, Location, and Profiles of Continuing Gentrification in Canadian Metropolitan Areas, 1981-2001,” Urban Studies 42, 9 (August 2005), 1569-1592.

[4] A journal article recently published by a project co-applicant reflects some of this research: Shannon Stunden Bower, “The Affordances of MacKinnon Ravine: Fighting Freeways and Pursuing Government Reform in Edmonton, Alberta.” Urban History Review 44, 12 (Fall/Spring 2015/16), 59-72.

[5] Jennifer L. Bonnell and Marcel Fortin, “Introduction,” in Historical GIS in Canada, eds. Jennifer L. Bonnell and Marcel Fortin (University of Calgary Press, 2014), xi.

[6] See for example: The Polis Center, “Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives,” Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, no date, retrieved from http://polis.iupui.edu/index.php/spatial-humanities/deep-maps-and-spatial-narratives/; L. Lippard, Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society (New York: The New Press, 1997); D. J. Bodenhamer, J. Corrigan, and T. M. Harris, eds., The Spatial Humanities: GIS and the Future of Humanities Scholarship (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010).

[7] Dwayne Trevor Donald, “Edmonton Pentimento Re-Reading History in the Case of the Papaschase Cree.” Journal of the Canadian Association for Curriculum Studies 2, 1 (2004), 23.

Latest posts by NiCHE Administrators (see all)

- 2024 David Neufeld Memorial Lecture: Tr’ondëk-Klondike Panel Recording - April 24, 2024

- ASEH Membership Survey: Future of Online Programming - April 18, 2024

- Call for Proposals: Toronto History Lecture 2024 - April 11, 2024

- Online Event – Environmental Perspectives in the History of the Levant - March 27, 2024

- Event – Book Talk – Camera Geologica: An Elemental History of Photography - March 19, 2024

- Shannon Stunden Bower Joins NiCHE Executive Committee - March 18, 2024

- Online Event – New Horizons for Portuguese Environmental History - March 13, 2024

- Event – Nerd Nite Edmonton #78: Rocks ‘n Roll - February 28, 2024

- Online Event – The Green Power of Socialism - February 13, 2024

- Hybrid Event – Early Insecticide Controversies and Beekeeper Advocacy in the Great Lakes Region - February 6, 2024

1 Comment